Blog series: Methods for Studying Density in the City, by Mel Nowicki & Tim White

‘Experiencing Density’ is a project jointly led by LSE Cities and LSE London that explores resident experiences of life in London’s new high-density housing. Researching the benefits, and pitfalls, of high-density housing in the capital has become ever-more pressing in light of Mayor Sadiq Khan’s promise to build more housing for a rapidly growing population, without infringing on the Green Belt.

However, whilst there has been growing interest in London’s high-density developments among architects, planners, and politicians, relatively few studies have investigated residents’ experiences. This is where our project comes in. We believe that asking residents about everyday life in these developments is critical for understanding what works, and what doesn’t.

This project is ultimately about people; their experiences, their opinions, their hopes for the future. It was therefore critical that our research methods captured these nuances, both when finding case study sites and engaging with residents. We are employing three different techniques to achieve this:

- ‘Density hunting’. Using Google Maps to explore the city and locate suitable case study sites.

- Posting letters with links to an online survey (via a web link and QR code)

- Resident workshops. Meeting with groups of residents to engage in more in-depth discussion and activities

Methodology decision-making processes and reflexive accounts of successes and failings are under-discussed in academia, with academics tending to focus on the polished final product. With that in mind, this series of blog posts will reflect on our three methods as the project unfolds, beginning with our first: ‘density hunting’ via Google Maps.

As is clear from a stroll around most parts of the city, London is densifying, with skyscrapers seemingly multiplying year on year, and new-build apartment complexes cropping up in relatively low-density contexts. Making a choice about which high-density developments to use for this project was therefore not easy. What did we want from our case studies?

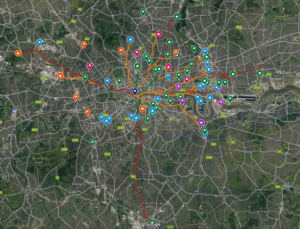

We decided to begin our ‘density hunt’ by using Google Maps’ 3D function to scout potential case studies. This meant ‘flying’ around Greater London looking for particularly large, intense developments.

We then followed this up with desk-based research on the developments to check whether they suited the following criteria:

- Was the development built within the last 10 years?

- Does the development have at least 200 housing units?

- Are there 100+ dwellings per hectare (a standard, if flawed, measure of density)?

We wanted to explore a range of building types, from tower blocks to lower-rise courtyard developments. We were also interested in investigating how high-density housing works across a range of locations in the capital. The chosen case study sites therefore occupy a variety of boroughs, north and south, east and west, inner and outer zones.

It could be argued that our understanding of high-density and its place within the urban landscape was limited by our Google-focused approach: should we not be ‘out there’ pounding the streets of the city in order to find the most suitable case studies? Is there something limiting in searching the city’s virtual counterpart rather than exploring the real thing?

Whilst warnings against ‘armchair research’ are valid, and being immersed in the field itself remains an integral research method, there are also huge benefits to the virtual city approach. Firstly, the ability to both ‘fly’ and ‘dive’ around the city. ‘Flying’ enabled us to examine the city from a birds-eye perspective, helping us to grasp not only the size and scale of individual developments, but also enabling us to assess the ways in which they fit (or don’t) into the wider context of the local area. For example, how do high-density developments in the relatively low-density borough of Ealing compare in terms of design, layout and size to developments in Elephant and Castle, a comparatively dense part of the city?

‘Diving’ then enabled us to zoom in on developments we found particularly interesting, examining their architecture and structure from a variety of angles and heights, something that might have proved problematic had we explored these areas on foot.

‘Density hunting’ using Google Maps therefore proved to be an effective way of both finding high-density developments across the city, and choosing case study sites that have a range of architectures and neighbourhood contexts.

Looking ahead methodologically, we have recently sent surveys to residents, posting letters to 500 homes per development (where development sizes exceed 500) that contain web links and QR codes directing residents to an online survey tailored to their specific development.

In the coming months, we’ll also be hosting workshops for residents of all nine case study developments here at the LSE. We’ll be using this time to work with residents to extend our understanding of both what people enjoy and what they find lacking in their high-density homes. The project will also result in a policy report, due to be published in September 2017, which we hope will feed into the Mayor’s new London Plan