This reflective blog summarises the major topics covered at our 29 October ‘New Housing and the London Plan’ workshop.

Accelerating new housing production in London: What works? Planning obstacles and practical innovations

Dr. Nancy Holman, Workshop Chair

On the journey home on almost any given day, Londoners are confronted by newspaper headlines decrying a crisis in the capital’s housing market. From garages selling for half a million pounds to beds suspended from ceilings renting for £175 a week, there seems to be abundant evidence that London’s housing market is dysfunctional.

Who is to blame? There are several stock explanations: “It is the fault of the planning system and by extension planners, as they are too rule- bound and artificially limit land supply” or “It is the fault of the developers and their greed, which drives them to bank land and eek out building slowly in order to keep prices high” or indeed “It is the fault of rich foreigners who buy London property as an investment and prevent locals from purchasing much needed housing.” These simplistic diagnoses reduce a very complex problem into neat cures: “eliminate planning”; “force developers to build”; “banish foreign buyers”. These could well do more harm than good.

With the idea of challenging some of these simplistic explanations, we hosted a workshop 29 October. Our goal was to try to identify the real barriers to development, and explore innovative solutions. We invited a group of well-informed stakeholders including local borough planners and academics, as well as representatives of RSLs, real estate consultancies and NGOs. The focus of our discussion was around real life examples of sites where:

- planning permission had been held up,

- permission had been granted but the development had not yet started;

- development was stalled; and

- these problems had been overcome.

Our goal was to brainstorm around best practices and ways of moving forward in a productive and realistic fashion.

Participants agreed that there are no simple answers: indeed, complexity itself represents a significant barrier to bringing sites forward and moving them smoothly through the development process. This complexity is not however restricted to the planning system—in fact, there was general agreement that further tinkering with a much adjusted and re-adjusted planning process would be very unwelcome (something to bear in mind when reading the Lyon’s housing review).

The kind of complexity that presents problems includes messy and often changing site ownership structures. These can result in protracted negotiations, in which aligning the goals of the various landowners, developers and the council can become almost impossible. And during the long time horizons involved in residential development, site ownership, politics, and economic context can all change—heightening risks for all.

The discussion also highlighted the role of planners as negotiators in a highly competitive market. Each new policy (targets ‘subject to viability’; CIL) brought with it another layer of uncertainty—and more possibilities for negotiation. The overall feeling was that targets for things like affordable housing should be both transparent and certain. Their malleability in reality means that they are always up for negotiation—and therefore seldom met. Planners felt particularly disadvantaged in viability negotiations. They often felt ‘worked over’ by developer’s teams of highly specialised ‘viability consultants’, since planners don’t generally have the financial skills to counter their assertions. Local authorities’ strengths were in policy and democratic accountability rather than financial manipulation, although many are rapidly working to build experience and expertise. This skills shortage drives many planning authorities to then commission specialist viability advisers. In all, the current system leads to planners getting ‘locked-in’ to lengthy and expensive ‘back-and-forth’ negotiations in order to achieve policy compliant outcomes—a process which can take months or even years.

In terms of solutions, ‘use it or lose it’ planning permissions met with resounding suspicion. It was felt that these offered nothing more than a token gesture toward trying to discipline developers into building and ignored the sometimes very real reasons why sites stalled. It also ignored the reality that, once a council had granted planning permission, it would be almost impossible for it not to re-issue permission upon reapplication. A refusal to do so would open up the LPA to the threat of appeal and the considerable expense this would necessarily entail.

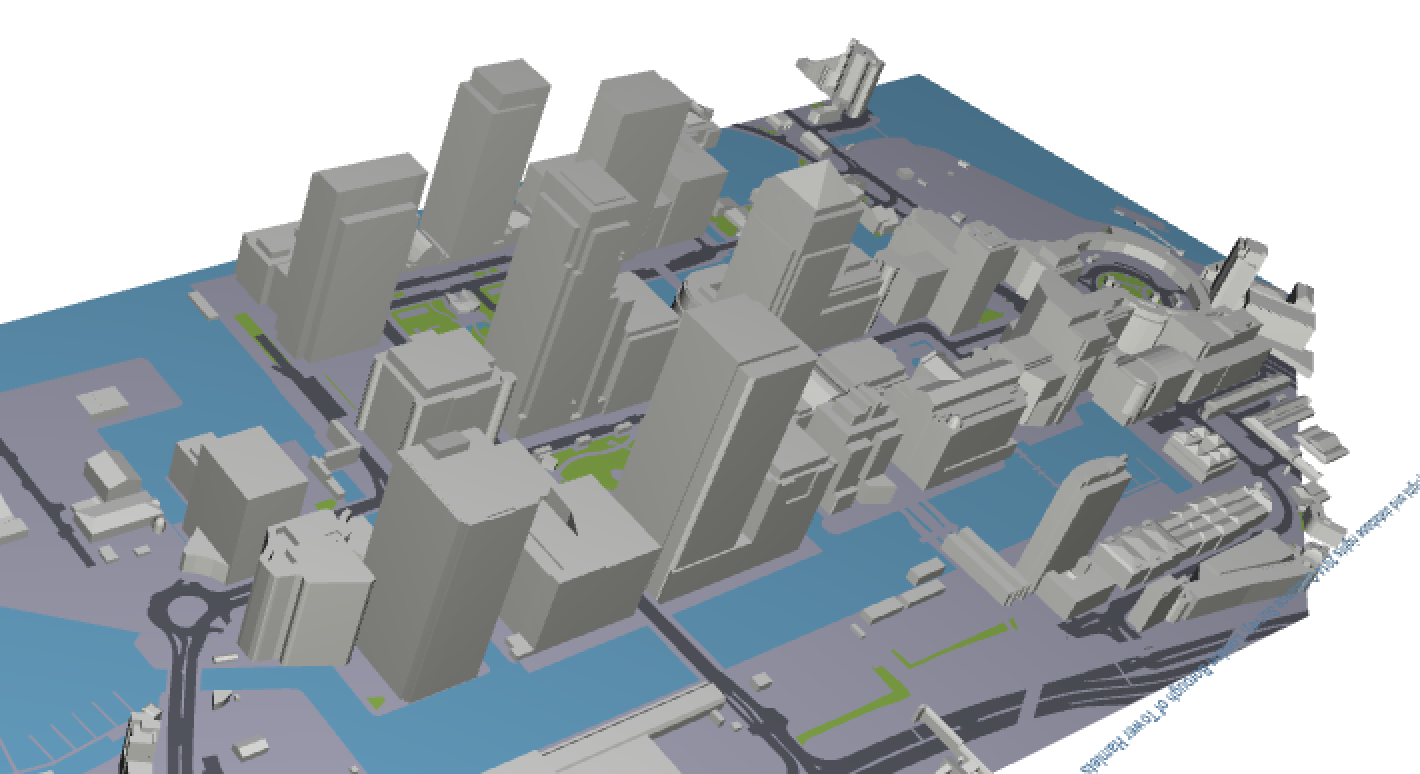

More promising was the idea of de-risking the process through parcelling large sites into smaller plots, allowing development to progress more speedily and evenly with varying developers. This would both reduce the risk involved in developing very large sites and allow a number of developers to proceed in parallel, thus speeding overall development of the site. Similarly, foreign investors (especially sovereign wealth funds) were seen to play a vitally important role in the London market, as they typically have very long time horizons and low costs of capital. Recent research indicated that about 20% of large London sites were owned or controlled by overseas investors.

There were also calls for rekindling of the role English Partnerships played in sites with infrastructure problems, like the Greenwich Peninsula and idea also mooted by the Lyons Review. There was also praise for Housing Zones, which allowed negotiation and trialling of innovative solutions—albeit only in a few small areas across London.

Our discussions suggested that barriers to housing delivery are not a simple affair: complexity, economic cycles, negotiation and politics all play their part in slowing down or speeding up housing delivery. There are however real advantages in considering how sites are parcelled, making viability calculations more transparent, looking at infrastructure provision and utilising programmes like Housing Zones to speed up delivery.

2 Comments