The rise and fall of the Department of Economic Affairs (DEA) parallels the promised but eventually unfulfilled modernization agenda of Harold Wilson’s government. The diary kept by Samuel Brittan for the fourteen months in which he served as an ‘irregular’ in the DEA provides a unique source for understanding the growth ambitions of the new government. Paul Brighton finds the diaries as a whole, with their excellent introduction and commentary, are inevitably an unintended elegy to an era of lost economic optimism — an optimism that was always built on sand.

Inside the Department of Economic Affairs: Samuel Brittan, the Diary of an ‘Irregular’, 1964-6. Roger Middleton (ed). Oxford University Press. April 2012.

Rows between the PM and GB? Surely not yet another volume of Alastair Campbell’s diaries of the Blair years! Turf wars between the Treasury and other departments? Uncertainty as to who is ultimately in charge of government economic policy? Yes, we know: Blair and Brown are throwing the crockery again!

But, hang on. It turns out history didn’t start in 1997 after all. This is 1964. The Prime Minister is Harold Wilson, the Chancellor is Jim Callaghan, and the year is 1964. Ok, so who’s “GB”? Why, the Secretary of State for Economic Affairs, of course: the Deputy Labour Leader George Brown.

But, if Callaghan is Chancellor, and Brown’s heading Economic Affairs, and arguably the most economically literate Prime Minister of the Twentieth Century is in 10, Downing Street, who’s actually running the economy? Perhaps we need an outsider to tell us: especially if it’s an outsider recruited to the inside.

Enter Samuel Brittan. Elder brother of the as yet unknown Leon, but already an influential Financial Times journalist, Brittan has been brought into the newly-founded DEA as a “Whitehall irregular”. He thinks he’s there to give George Brown the benefit of his economic insights. Brown, however, may just have pulled a fast one, and co-opted the well-known journalistic analyst of the Tories’ thirteen years of Treasury misrule as a speechwriter and proto-spin doctor.

If we’re hoping for immediate insights into the inner sanctum of economic policy making, day one is a little bit of a disappointment. “Gloomy toilet with no soap or towel. I donated a piece of soap to the toilet, which afterwards vanished.” But surely some insider analysis can’t be long in coming. “Apparently suggestion of a modern type ticking roller towel has never got anywhere in Whitehall!”

However, the Whitehall turf battles soon take a turn for the better. By Day Four: “Have got own ‘secretary’ – an elderly audio-typist who is trying to cope!” Soon, he ascends to the dizzy heights of having three telephones on his desk. “Then one was put on the floor and started ringing! A grey-beige one was put in and then disconnected and then put in again.” This, perhaps, if it were a French symbolist narrative, might stand as a motif of British economic policy in the 1960s.

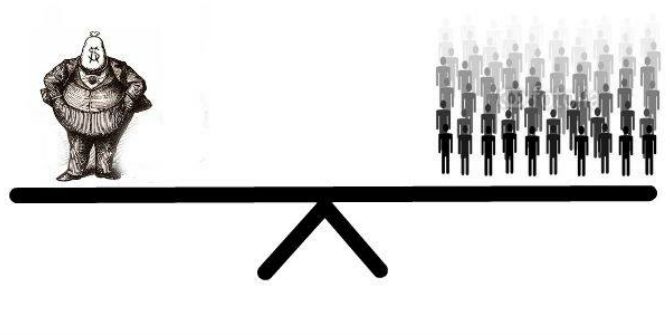

Harold Wilson believed in “creative tension” between the new DEA and the Treasury; and, as has often been remarked, if the creativity was occasionally hard to spot, the tension was never in short supply. Wilson was arguably a much more literal triangulator than ever Blair or Clinton managed to be. The only difference was that his triangulation was all about personnel. Elected as the left-of-centre candidate for the Labour leadership on the sudden death of Hugh Gaitskell in early 1963, by an essentially Rightist parliamentary Labour Party, what could be better than to deploy his two more-or-less Gaitskellite leadership campaign opponents in positions where they would essentially be fighting each other for control of the management of the economy, rather than fighting him for the leadership and the premiership?

Popular wisdom suggested that it was all concocted between Wilson and the runner-up Brown in the back of a taxi. In fact, the idea of a separate DEA had been much longer in the planning. At its heart was the idea of the tactical, day-to-day Treasury managing the currency and the short-term fluctuations of the markets, and agreeing the appropriate fiscal and monetary responses; while the DEA took the strategic view, coming up with a brand-new National Plan to help Britain plan its economic priorities for the years ahead.

The key question, however, rarely explicitly answered at the time, was whether the National Plan was some grand, democratised Soviet-style economic blueprint; or merely a rebranded version of the mildly interventionist National Economic Development Corporation (known colloquially as NEDY, along with its more specialised offshoots, the “little NEDDIES”) of the later Tory years. Macmillan, Douglas-Home, and their Chancellor, Reggie Maudling (for whose economic policies Brittan frequently utters secret paeans of praise in the privacy of the diary) had already taken several steps along this dirigiste path in the early 1960s.

This, incidentally, gives us the best of the relatively few witticisms in the book. George Brown, as is well documented, was often (in the journalistic phrase) “tired and emotional” after downing more than a few drinks at evening functions. His absences from meetings the following morning were euphemistically described as “morning sickness”. After one too many of these absences, a sardonic Wilson enquired as to whether Brown’s morning sickness meant that he was about to give birth to a little NEDY!

The diaries as a whole, with their excellent introduction and commentary, are inevitably an unintended elegy to an era of lost economic optimism. But the optimism was always built on sand. A National Plan erected on the foundations of a refusal even to contemplate the option which might have smoothed its birth – the devaluation of the pound – was always doomed. Samuel Brittan’s own involvement lasted for just fourteen months. After that, he returned to journalism, and to the task of updating his book on recent Treasury history. The pound endured at its post-war level for a further twenty-two months. The DEA experiment effectively ended with the onset of economic crisis and Brown’s departure in 1966 (although it continued in shadowy form in other hands for a while longer). Callaghan was shifted after the inevitable forced devaluation in 1967. Meanwhile, Harold Wilson, like John Major after Black Wednesday in 1992, survived in office, while being obliged to extol the virtues of an economic policy he had spent his first years in office lifting heaven and earth to avoid. By the General Election of 1970, the defence of the pound, like the DEA itself, was barely a distant memory.

——————————————————————————–

Paul Brighton is Head of Department of Media and Film at the University of Wolverhampton. He grew up in Wolverhampton. He attended Wolverhampton Grammar School, and won an Open Scholarship to Trinity Hall, Cambridge. He got a First in English and, after postgraduate research at Cambridge, worked for the media. He was a BBC Radio presenter for twenty years, before becoming Head of Broadcasting and Journalism at University of Wolverhampton. His book “News Values” was published by SAGE in 2007. He is now Head of Media, Film, Deaf Studies and Interpreting; and his next book “OrIginal Spin: Prime Ministers and the Press in Victorian Britain” will be published by I.B. Tauris next year. Read reviews by Paul.

If anyone is interested in taking a look at Sam Brittain’s original diaries they can be found in the Archives of LSE Library – the reference is COLL MISC 0745.