In recent years, it has become increasingly clear that emotion plays a central role in global politics, and here Andrew Ross analyses high-emotion events such as protests and speeches to explore how they shape public perceptions. Case studies cover the war on terror and violence in Rwanda and the Balkans, with Ross identifying important sites of emotional impact missed by earlier research focused on identities and institutional interests. Megan Daigle finds that this book represents a needed challenge to the rationalist perspective of much of IR theory; one which takes the challenge and potential of emotions seriously, while refusing to deny or gloss over the messiness of the politics of emotion.

Mixed Emotions: Beyond Fear and Hatred in International Conflict. Andrew Ross. University of Chicago Press. January 2013.

The discipline of international relations, as traditionally conceived, subscribes to liberal notions of reason and emotion. That is, it understands the former as the gold standard of analytical thought and action, while the latter is seen as an unwelcome distortion, to be controlled and suppressed. It is refreshing, then, to see Andrew Ross, an assistant professor of political science at Ohio University, urging us to consider the complexity and even the necessity of emotions in understanding conflicts of all kinds. In Mixed Emotions: Beyond Fear and Hatred in International Conflict, Ross argues that “emotions, far from rote impulses, are creative forces with potential to disrupt business as usual in the world of politics” (p.40).

Ross starts out from the contention that viewing conflict necessarily as an expression of hatred “prefigures the emotional landscape” – limiting our understanding of how conflicts escalate and our capacity to rebuild communities in their wake (p.19). Ross draws from neuroscience and microsociology, weaving in insights from international relations, cultural, and political thought to theorize what he calls circulations of affect – a way of understanding how emotions shift, transfer, and generate political effects across time, space, and levels of analysis. Emotions are both contagious and creative, spreading amongst people, groups, and locales in ways that can certainly be destructive, but equally possess the potential for creativity and even restoration. As Ross argues, “[e]ach synthesis is an opportunity for change” (p.45). These processes do not happen in a planned, controllable, or even conscious way; rather, Ross argues that “we routinely soak up and replicate the affective expressions around us” (p.23).

Ross starts out from the contention that viewing conflict necessarily as an expression of hatred “prefigures the emotional landscape” – limiting our understanding of how conflicts escalate and our capacity to rebuild communities in their wake (p.19). Ross draws from neuroscience and microsociology, weaving in insights from international relations, cultural, and political thought to theorize what he calls circulations of affect – a way of understanding how emotions shift, transfer, and generate political effects across time, space, and levels of analysis. Emotions are both contagious and creative, spreading amongst people, groups, and locales in ways that can certainly be destructive, but equally possess the potential for creativity and even restoration. As Ross argues, “[e]ach synthesis is an opportunity for change” (p.45). These processes do not happen in a planned, controllable, or even conscious way; rather, Ross argues that “we routinely soak up and replicate the affective expressions around us” (p.23).

Moving forward, Ross takes the reader through four conflicts that demonstrate how the politics of emotion can circulate in fluid and sometimes unpredictable ways. First, he traces the figure of “the terrorist” in the post-9/11 United States, and how a prevalent mood of fear allowed coded racism to steer suspicion towards Middle Eastern, Arab, and Muslim people in the United States, in spite of discourses of a supposedly post-racial America. Government reports, political speeches, legal documents, and other sources help to construct the environment where panic over 9/11 migrated into fears of anthrax and eventually into Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, which might not otherwise have seemed connected. From that point, actions ranging from racial profiling onboard planes to the Iraq invasion were seen as justified – by the circulation of fear and by the “borrowed emotional viability” of rhetorical allusions to Pearl Harbor and World War II (p.75). Through the lens of the 2004 train bombing in Madrid, Ross shows that there was nothing automatic or assured about the American response. Where the United States turned its suspicion and anger against faceless but ubiquitous “terrorists”, Spain blamed its tragedy on its own government for inviting trouble by its military engagement in Iraq. This difference shows the complexity and specificity of affective circulations, wherein blanket terms like fear “stand in for an array of intersecting and reciprocally amplifying emotions” (p.91).

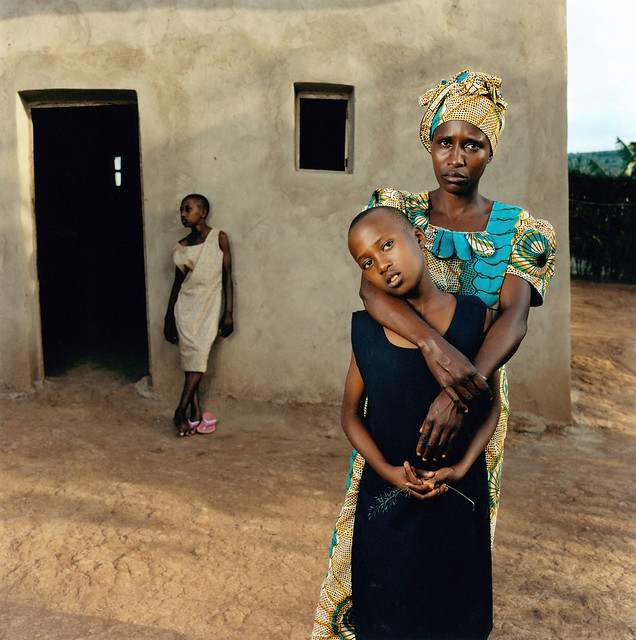

Next, Ross addresses the notion of hatred through an engagement with the genocides in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. In both cases, a complex web of memories, tensions, and events led to the outbreak of genocidal violence, but to conceptualise either as the result of “cycles of hatred” – as is often done in the study of ethnic violence – is reductive and conceals the ambiguity, flexibility, and complexity of emotions at play. Ross argues that, in fact, hatred was rarely expressed amongst the perpetrators of genocide; instead, respondents spoke about jealousy, despair, and honour. He maps out some of the elements which precipitated violence, including reburials of the dead from World War II in Yugoslavia and inflammatory public speeches in Rwanda, showing how each can be said to contribute to shifting and interacting circulations of affect. The public expression of normally private events such as burials created audiences, amongst whom ideas and interactions could reverberate. While elites, often accused of orchestrating genocide, could intervene in affective circulations, they could neither control them nor guarantee that their attempts would turn out as planned.

Ross concludes the book by arguing that, “[i]nstitutions concerned with reducing violence cannot afford to assume that emotions are obstacles rather than resources for justice and social repair” (p.125). Social repair, in this instance, is the re-establishment of daily routines and rituals of everyday life, in concert with communities, neighbours, and families. It is a process of “emotion-generating interactions at the microlevel” that differs fundamentally from reconciliation, which too often focuses on suppressing emotion and pushing a single version of events (p.139-140). Ross points to the gacaca community courts in Rwanda, which gave survivors of the genocide the chance to be heard and to vent their emotions through giving testimony. He posits that the gacaca courts, despite their failings, “highlight the importance of treating popular emotions as resources rather than obstacles in the pursuit of justice” (p.147).

A major strength of this book is Ross’s refusal to deny or gloss over the messiness of the politics of emotion. He sets out to, in his own words, “account for the political significance of emotions without cleansing away the distinctive properties that make them elusive as topics of study” (p.2). Though it would be tempting to sand off the edges of such a nebulous and temperamental topic, Ross resists. It would be interesting to see him push that uncertainty even further, engaging not just with the circulation but also the quality of emotions. Ross calls hatred a reductive notion that belies complexity and variety in affective politics, collapsing together emotions such as jealousy, despair, honour, anger, pride, and even hope. He does not tell us what differentiating such emotions would look like, or what it could potentially do, in the arena of international conflict.

Ross’s book represents a needed challenge to the rationalist perspective of much of IR theory, one which takes the challenge and potential of emotions seriously. It paints emotions not as the unreliable contaminants of Enlightenment thought, but rather as creative forces with the potential to inspire, heal, and forge movements for change through what he calls collective agency. It is also anti-essentialist: by theorizing ways that interactions and connections can happen across demographics, groups, and spaces, Ross enables us to look at conflicts like those in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia without relying on static understandings of ethnicity and identity. Scholars and practitioners of transitional justice, as well as IR theorists, should find this book very useful and interesting.

——————————

Megan Daigle is a writer and researcher whose work focuses on international politics, gender, race, and sexuality. She is currently a postdoctoral research fellow at the Gothenburg Centre for Globalization and Development working on sexual violence in conflict. Her book, titled From Cuba with Love: Sexuality and the Governance of Bodies in Post-Soviet Cuba, is under contract with the University of California Press. She tweets @megandorothea. Read more reviews by Megan.

1 Comments