The Victorians worried about many things, prominent among their worries being the ‘condition’ of England and the ‘question’ of its women. Sex, Crime and Literature in Victorian England aims to revisit these particular anxieties, concentrating more closely upon four ‘crimes’ which generated especial concern among contemporaries: adultery, bigamy, infanticide and prostitution. This book encourages us to question and critique not only the complex and often contradictory Victorian responses to sex and crime, but also to reflect on the ‘condition’ of our country today. Through the interweaving of issues of law, violence, sex, criminality, and misogyny, Ward produces a book ‘about’ much more than a nation’s salaciousness, writes Sophie Franklin.

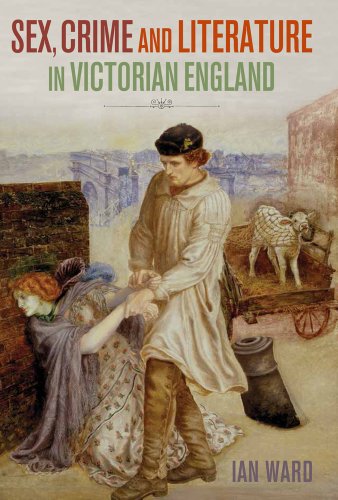

Sex, Crime and Literature in Victorian England. Ian Ward. Hart Publishing. February 2014.

Sex, Crime and Literature in Victorian England. Ian Ward. Hart Publishing. February 2014.

The Victorians are often identified as notoriously prudish when it comes to sex. Yet, as Ian Ward’s Sex, Crime and Literature in Victorian England proves, beneath this straitlaced veneer lay nineteenth-century society’s prurient desire to read about sex and crime in novels and newspapers. Ward, Professor of Law at Newcastle University whose previous publications include Law, Text, Terror (2009) and Law and the Brontës (2011), weaves together fact and fiction, law and literature, in an interdisciplinary study that implicitly reflects on the modern world, particularly in light of recent instances of violence against women such as the murder of Farzana Parveen in Pakistan and the Isla Vista killings.

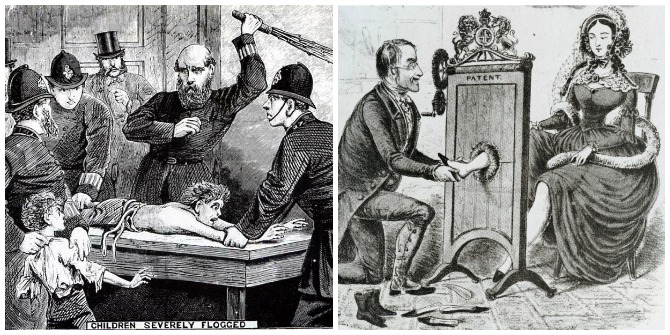

Each chapter approaches the Victorian cultural and literary environment from a legal perspective, focusing on laws which encapsulate a central nineteenth-century concern: Lord Ellenborough’s Act of 1803 which redefined the terms of the 1623 Infanticide Act; the Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857 which introduced the Divorce Court; and the Contagious Diseases Act of 1864 which aimed to curb the prevalence of prostitution by targeting women and not clients. A reciprocal relationship emerges between these laws (amongst others) and the writings of contemporary authors and activists: both feed into and off one another, with the latter often satirising the former, and the former sometimes resembling a sensationalised version of the latter. Through this oscillating proximity, the boundary between law and literature in nineteenth-century England was destabilised.

Ward writes that his study is ‘about sex and marriage, and the consequences, legal and otherwise, of transgressing the Burkean norm’ (p.3). Whilst it is undoubtedly concerned with these issues, it is also about women: the restrictive feminine ideal with which they had to contend; the laws which aided male dominance; the writers, campaigners, and feminists who challenged the propagated Angel in the House mould. Most, if not all, of the laws considered by Ward sought to regulate female sexuality. This was true of the Obscene Publications Act in 1857, introduced following Flaubert’s trial for the apparent obscenity of Madame Bovary. Despite the law’s ‘legislative inefficacy’, its implementation was ‘testament both to the rise of the literary text and its presumed [sexual] danger’ (p.144), mainly to naïve and, therefore, apparently seducible young married women (p.59). As Barratt Browning’s Casa Guidi Windows attests, ‘men made the laws’ (p.142).

The first chapter opens with the Norton v Lord Melbourne case, an example of a crim-con (criminal conversation), a law action based on the ‘fiction’ that a man, having committed adultery with a married woman, had ‘trespassed on the goods of the husband’ (p.29). Crim-cons were seen as entertainment for the public and damaging to those involved, particularly (and predictably) the accused adulteress. Caroline Norton, social reformer and author, was one such woman. The Norton v Lord Melbourne case (which denied Caroline her voice in court) positioned her as not only an influence for the literary depiction of ‘fallen middle-class women’ but ‘as a reader referent’ (p.31). She became a spectral figure haunting subsequent works such as Ellen Wood’s East Lynne, the most successful novel published in Victorian Britain in terms of sales (p.46). These texts, and Caroline Norton’s experience, revealed the extent of the law’s prejudicial preference of men; upon marriage, a woman’s property became her husband’s, and her ‘very being’ was suspended (p.34). Furthermore, as Thackeray’s The Newcomes shows, the ‘marriage market’ reduced matrimony to a form of prostitution, forcing (middle- and upper-class) women into financially desirable but personally unwanted unions (p.40).

Books like The Newcomes and cases like Norton v Lord Melbourne embodied the ‘deepest fears of a generation’ (p.57). Yet the disquietude surrounding adultery and women’s (legal) position in society were not the only circulating concerns with sexuality in Victorian England. As the third chapter, ‘Unnatural Mothers’, indicates, the issue of infanticide was a popular source of anxiety heightened by the nineteenth-century ‘cult’ of motherhood (p.90). Illegitimate children, fallen women, and ‘murderous mothers’ were staples of mid-nineteenth-century fiction (p.117), with Ward focusing on George Eliot’s Adam Bede and Frances Trollope’s Jessie Phillips, both of which involve accusations of child-murder; and Elizabeth Gaskell’s Ruth, which follows Ruth from her illegitimate pregnancy to her eventual redemption (and death).

The discussion of spousal violence in Anne Brontë’s The Tenant of Wildfell Hall and Eliot’s Scenes of Clerical Life is particularly interesting, since it addresses the realism of representing domestic violence (p.93). These were not merely sensationalist texts seeking sales; Eliot and the Brontës sought to create art that was ‘concrete’, a reflection of people’s everyday reality, one often based on violence, misogyny, and cruelty (p.93).

In the final chapter, ‘Fallen Angels’, Ward turns his attention to prostitution, quoting Annie Besant’s succinct summary which still resonates today: ‘Men are immoral for their amusement; women are immoral for bread’ (p.122). Yet, under the Contagious Diseases Act, rather unsurprisingly, it was the women who were targeted and criminalised. Sexually transmitted infections were added to the growing list of Victorian fears. This new law protected soldiers and sailors from contracting venereal diseases by enforcing invasive inspections on prostitutes, thereby ‘saving the Empire’ (p.125). Feminists such as Florence Nightingale decried this measure, since it ‘perpetuated vice and legitimated the systematic ‘torture’ of women’ (p.126). Such debates surrounding prostitution, its regulation, and even the illegalisation of it continue in the UK today, underscoring the lack of substantial progress in the past century.

Throughout the book, Ward refers repeatedly to ‘we’, creating complicity between author and reader. Like Ward, ‘we’ become ‘troublesome’ critics who insert ‘still further layers of prejudice and uncertainty between author, reader, and text’ (p.147). By placing readers as critical participants, Sex, Crime and Literature encourages us to question and critique not only the complex and often contradictory Victorian responses to sex and crime, but also to reflect on the ‘condition’ of our country today (p.148). Through the interweaving of issues of law, violence, sex, criminality, and misogyny, Ward produces a book ‘about’ much more than a nation’s salaciousness.

———————————————

Sophie Franklin is currently completing her MA in English Literary Studies at Durham University, having graduated from the University of St Andrews in 2013. Her main research interests lie in nineteenth-century literature and society, particularly the Brontës, power, violence, ‘thing theory’, and representations of gender. For her MA thesis, she is examining the psychological significance of literal and metaphorical windows in George Eliot’s novels. Following her graduation from Durham, she hopes to pursue doctoral research on the violence of the Brontës’ work. Read more reviews by Sophie.

1 Comments