In this contribution to the field of philosophy, the author John Charvet is dissatisfied with the literature to date which has as its focus the justification for, and any limits of, Human Equality, writes Josh Jowitt. Charvet’s theory as presented in The Nature and Limits of Human Equality has been successful in that it has provoked renewed questioning of assumptions which we are frequently guilty of taking for granted, but is also not without its drawbacks.

The Nature and Limits of Human Equality. John Charvet. Palgrave Macmillan. 2013.

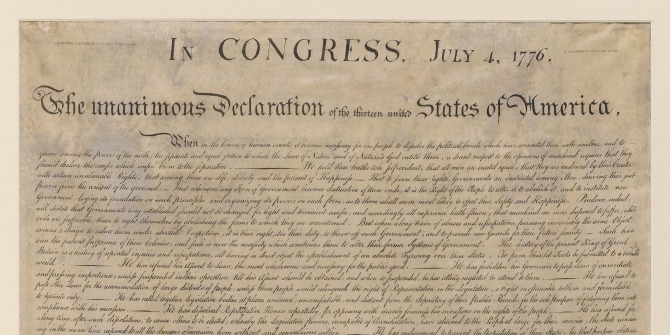

The founding fathers of the American Republic held the fact that all men are created equal to be a self-evident truth which required no justification beyond its initial statement in the Preamble of the 1776 Declaration of Independence. Such a sweeping statement appears to fit nicely within the prevailing attitudes of the Enlightenment during which the proclamation was issued, yet the curious observer may find themselves asking why, if Human Equality is as self-evident as Thomas Jefferson believed, it required stating so clearly and prominently; if something were truly self-evident, then a mere restatement of the idea is philosophically and politically valid. This apparent contradiction therefore reveals Human Equality to be a more controversial idea within philosophy than we may wish to recognise, particularly when it comes to a universally acceptable reason for that equality, and it is this debate that John Charvet has entered with this contribution to the field.

Like many whose scholarly interest lies in political theory, Charvet is dissatisfied with the literature to date which has as its focus the justification for, and any limits of, Human Equality. He begins his work, for example, by claiming that Western Ethics will only see political theories as serious if they begin with the substantive – as opposed to merely formal – equality of the individuals which form their subject. Such equality is assumed to be inherent within the concept of morality, in that it is incompatible with a moral attitude to governing interpersonal relationships to prioritise the interests of some over others without appropriate justification. For Charvet, such a statement is circular; equal consideration of interests presupposes an acceptable justification to consider us as equal.

Chapters Two and Three are devoted to providing specific examples of this circular argument and other problems within Ancient Ethics and Natural Law Theory, and Individualist Ethical Theories respectively. Chapter Two in particular provides an interesting narrative on the evolution of the ancient inegalitarian positions of Plato, Socrates and Aristotle into the modern egalitarianism of Locke. Chapter Three also provides a useful summary of several Individualist justifications, including those of Vlastos, Gewirth, Dworkin and Rawls, before dismissing them for reasons of presupposition of equality or their beginning from an internal as opposed to an external viewpoint – the latter Charvet holding as essential for the operation of rights in any society given their basis on agential interaction. These various objections are summarised by Charvet into a meta-claim, something he names the ‘Standard Justification for Equality’ and which takes the following form:

- Individuals are intrinsically, inherently or objectively valuable, or are ends in themselves.

- Such value is possessed by virtue of a feature of their nature; rational agency, the ability to value, moral personality and the capacity to shape our lives are given as examples from the Individualist literature.

- Individuals are unable to claim their intrinsic value from this feature without recognising that all who possess the same feature possess equal value.

- If Human Beings possess the same feature and same value, and are therefore substantively of equal worth, they are entitled to mutually limiting equal rights.

Charvet is of the belief that this standard justification is flawed in its outset, as it seeks to justify value for people from the fact of their personhood; he asks why we should not equally value fish from the fact that they are fish? From this objection he begins Chapter Four, where he attempts to establish a new theory to justify the Equality of Individuals based on their participation in an Ethical Community. He argues that, if we believe that ethical worth arises from the interaction that is necessary from membership of a given community, it follows that members of a given community can be conferred through the collective will of the same community. To be successful, any Ethical Community must have a structure of rights and duties which are sufficient to foster a sense of community; members must be confident that other members will comply with their duties and obligations; and sanctions must exist to protect the community from free-riders. From this, Charvet proposes that an Ethical Community based on the Individual themselves rather than based on their role in the community would be preferred, before using the last three chapters of the book to distinguish his new theory from existing communitarian theories and to discuss its practical application on a global scale.

Charvet’s aim is both admirable in its attempt to plug the gaps which he sees in the existing literature, and extremely ambitious its scope – especially for a book which is under two-hundred pages in length. At times, the narrative feels as though it could have benefited from more space. In particular, Charvet’s dismissal of Gewirth’s Principle of Generic Consistency appears at best to be incomplete in its appraisal of the theory, or at worst to misunderstand both the dialectical nature and limited claims of the Gewirthian argument. Additionally, in claiming that an Individualist Ethical Community is preferable to a Role-Based one, it is not immediately clear how such a community would avoid the presupposition of freedom and equality of individuals which the entire book is supposed to circumvent. Chapters five to eight are also problematic in that, although they provide excellent summaries of Communitarian though and Theories of Global Justice (Rawls’ Law of Peoples in particular), little to no attempt is made to discuss the extent to which a theory of Human Equality based on the Ethical Community may overcome the difficulties highlighted by Charvet as extant in the existing literature.

Despite these criticisms, Charvet’s theory as presented in this book has been successful in that it has provoked renewed questioning of assumptions which we are frequently guilty of taking for granted. In thus highlighting deficiencies with existing thinking from several schools throughout history and proposing what he believes is a superior alternative, Charvet’s piece will no doubt be of great use to those working in the field.

Josh Jowitt is second year PhD Candidate at Durham Law School, studying the ever-controversial link between law and morality. He is particularly interested in the theories of John Rawls and Alan Gewirth. He also leads tutorials and seminars in Public Law modules at both Durham and Newcastle Universities. Read more reviews by Josh.