In Biopolitical Media: Catastrophe, Immunity and Bare Life, Allen Meek examines the development of media through a biopolitical lens, arguing that the circulation of imagery since the 1840s is implicated in the systematic cataloguing of human life, the increasingly mechanised mass slaughter of animals and humans and biological conceptions of life and death. Ruth Garland finds that while this complex and fascinating interrogation may not always fully convince, it will encourage readers to critically examine how images of violence and catastrophe exercise power over our lives.

Biopolitical Media: Catastrophe, Immunity and Bare Life. Allen Meek. Routledge. 2016.

Biopolitical Media: Catastrophe, Immunity and Bare Life examines catastrophe not through themes of collective memory or trauma, but at one remove, through the media’s role in recording humans as biological entities and in capturing our attention through shock. Allen Meek uses Michel Foucault’s conceptualisation of the technological power and control over populations through biopower and biopolitics to look at how the growth of imagery since the 1840s relates to the systematic cataloguing of human life, the increasingly mechanised mass slaughter of animals and humans and decisions about who is allowed to live and who must die.

Biopolitical Media: Catastrophe, Immunity and Bare Life examines catastrophe not through themes of collective memory or trauma, but at one remove, through the media’s role in recording humans as biological entities and in capturing our attention through shock. Allen Meek uses Michel Foucault’s conceptualisation of the technological power and control over populations through biopower and biopolitics to look at how the growth of imagery since the 1840s relates to the systematic cataloguing of human life, the increasingly mechanised mass slaughter of animals and humans and decisions about who is allowed to live and who must die.

Throughout the book Meek maintains the intriguing idea that measured doses of images such as those depicting ‘mass death of civilians in concentrated spectacular forms’ (152) – as at Hiroshima and in the aftermath of the liberation of the Nazi death camps – provide crisis narratives that ‘inoculate’ us against ‘the constant threat of catastrophic destruction’ (3). At the level of the nation state, a shocked, disoriented, anxious and hence passive population enters into a ‘collective regression’, which gives those in power the opportunity to reduce freedoms, intensify surveillance and undertake economic restructuring in favour of elites. At the individual level, he argues that ‘images of death or suffering enhance the lives of those who view them by intensifying feelings of anxiety, numbing, emotional response or allowing voyeuristic pleasure’ (142).

This is a difficult and complicated argument to sustain and I had many objections along the way, but the journey was fascinating. Above all, the book allows the reader to consider some of the profound, as yet barely understood, consequences of the mass circulation of documentary imagery, and how this impacts on our understanding of ourselves and the ways in which power over populations is exercised. Meek is not afraid to be controversial: for example, when he claims that 9/11 was inflated to the status of iconic trauma by a ‘media apparatus’ which, far from being designed by ‘foreign agents’, actually played on narratives that ‘had already been constructed over decades by America’s own intellectuals and the media’ (151). He provides little or no evidence for the social mechanisms that might account for this, but at least he is questioning some of the assumptions behind our mediated understandings of history.

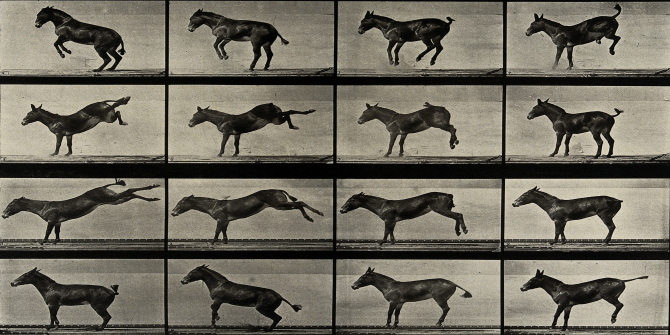

Image Credit: V0048757. A horse rearing and bucking. Photogravure after Eadweard Muybridge (Wellcome Images)

Image Credit: V0048757. A horse rearing and bucking. Photogravure after Eadweard Muybridge (Wellcome Images)

One of the most coherent, well-argued and evidenced sections of this book concerns the role of US imperialism during the 1940s and 1950s in using censorship and sensation to reinterpret the post-war world. Meek asks why images from Belsen and Dachau were withdrawn after a dramatic initial exposure, and why images and experiences described by the victims of Nagasaki and Hiroshima were withheld from public circulation, although he does not give a satisfactory answer. At the same time, he argues, both catastrophes were used by US scientists to explore the limits of human suffering and resilience and the long-term impacts of trauma, and, indeed, both acts of mass destruction incorporated their own scientific study. The contrasting ‘dynamic of concealing and revealing the spectacle of bare life’ after Hiroshima and the liberation of the camps was political, serving to bolster West German democracy and define the USSR as the totalitarian enemy rather than the Nazis.

Meek also considers this period through the lens of individual experience, to show how a single act of mass destruction, beamed around the world, can expose whole populations to unconscious anxieties about depersonalisation and death, in which one’s own death is forever overshadowed by the possibility of biological extinction. Recalling her first encounter in 1945 with images from the Nazi death camps, Susan Sontag describes the deadening process:

‘When I looked at those photographs, something broke. Some limit had been reached, and not only that of horror. I felt irrevocably grieved, wounded, but a part of my feeling started to tighten; something went dead, something is still crying’ (cited, 131).

Less successful for me were his claims that the nineteenth-century obsession with scientific classifications, such as in Jean-Martin Charcot’s early definitions of psychopathology or the use of statistics which led to the hygiene movement, was inherently dehumanising. The pioneering study of Dr John Snow linking contaminated water with the 1854 London outbreak of cholera, for example, is surely a triumph for the science of epidemiology and humane public policy. Similarly, the classificatory work by Linnaeus on biological taxonomy and Dmitri Mendeleev on the periodic table are works of beauty as well as knowledge. The captivating images by Eadweard Muybridge, photographing the movement of horses for the first time, come in for criticism because they enabled a mechanical, industrial interpretation of animal life, which, albeit by a roundabout route, ultimately led to the industrialisation of human slaughter. Meek’s broader concerns, about the role of moving images in narcotising and dissociating audiences from the realities of life and death, remain pertinent, however.

Paradoxically, having identified the Holocaust as a catastrophe, Meek then argues that it should not be seen as exceptional, but as having continuities with the genocides perpetrated by colonial powers, for example, during the four centuries of the Atlantic slave trade. It could be – and surely must be – both. The contemporary decapitation videos showing the slaughter of humans as animals should be seen in the context of the use and abuse of atrocity images under Western hegemony, the author states. Today, as inhabitants of ‘mediated worlds’, Meek concludes, we are used to ‘parrying the shocks’ provoked by images of violence (142) and constructing ourselves as the ‘wounded body politic’ (152) in need of care and protection. Instead of investing such imagery with superstitious fear or veneration, we should critically examine its potential to exercise power over our lives.

Ruth Garland is a PhD researcher in Media & Communications at the London School of Economics, researching into government communications. She originally studied human sciences and spent twenty years in public sector media relations. Read more reviews by Ruth Garland.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.