If the relationship between people and politicians seems marked by a sense of perpetual distrust, how can truth and freedom be returned to democratic politics? In Foucault’s Political Challenge: From Hegemony to Truth, Henrik Paul Bang traces an alternative model of the political through the scholarship of Michel Foucault, focusing particularly on his conception of parrhēsia. Reviewed by Andreas Aagaard Nøhr.

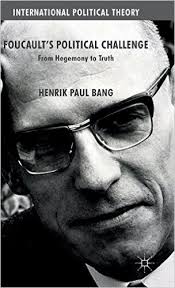

Foucault’s Political Challenge: From Hegemony to Truth. Henrik Paul Bang. Palgrave Macmillan. 2015.

Democracy is in bad shape: the people do not trust their politicians; the conventional parties are unable to represent and mobilise the people; the demise of popular sovereignty – brought on by global capitalism – seems eminent; and the powerlessness felt in the general populace results only in growing anger and enmity towards the outside. These complaints are all too familiar. In Foucault’s Political Challenge: From Hegemony to Truth, Henrik Paul Bang’s diagnosis of the problem is not all that different: ‘modern democracy will experience increasing crisis tendencies if it does not find new ways of reconnecting politicians and people in terms of a political and democratic model of speaking truth and practicing freedom at all levels, from the personal to the global’ (pxiii). In other words, democratic politics, in whatever form we find it in the world today, is unable to produce truth and freedom.

Democracy is in bad shape: the people do not trust their politicians; the conventional parties are unable to represent and mobilise the people; the demise of popular sovereignty – brought on by global capitalism – seems eminent; and the powerlessness felt in the general populace results only in growing anger and enmity towards the outside. These complaints are all too familiar. In Foucault’s Political Challenge: From Hegemony to Truth, Henrik Paul Bang’s diagnosis of the problem is not all that different: ‘modern democracy will experience increasing crisis tendencies if it does not find new ways of reconnecting politicians and people in terms of a political and democratic model of speaking truth and practicing freedom at all levels, from the personal to the global’ (pxiii). In other words, democratic politics, in whatever form we find it in the world today, is unable to produce truth and freedom.

Bang’s main target is clear: theories of agonistic democracy (Chantal Mouffe, Jacques Rancière and Giorgio Agamben) and deliberative democracy (Jürgen Habermas and John Rawls) share, according to Bang, the view that obedience is the condition of free reasoning in the res publica, a view also found in Immanuel Kant’s essay What is Enlightenment?. To challenge these prevailing theories, the author explores Michel Foucault’s conception of politics and the political throughout his writings.

In Foucault, Bang finds an alternative model for the political which is neither conflict nor consensus, but a space where:

subject, power, discourse and truth fuse and condense as evidence of an open, self-transforming, reproductive, communicative and interactive authority relationship between political authorities, as incumbents of authority roles, and laypeople as ordinary members of a political community. ( 4)

The code of the political, then, is the acceptance/non-acceptance of political authority and its production of truth. Bang’s solution to the problem of democracy therefore is that ‘[w]hat we should emphasize much more today is the possibility of introducing the model of good parrhēsia as an alternative to the models of the extraordinary decision-maker and the ordinary exception’ (37) – the models of Carl Schmitt and Agamben. Strictly speaking, Bang wants the democracies of today to operate on the basis of persuasion rather than political rhetoric or the hiding of authority behind law. What is missing from the political in the present are values of sincerity and authenticity, which does not mean that politics loses its agonistic structure, but rather that we should respect and cherish plain and frank speech within it.

Image Credit: (boulanger.IE CC 2.0)

Image Credit: (boulanger.IE CC 2.0)

The book has three parts, all made up of well-trodden paths for readers of Foucault. The first section discusses how the government by truth (parrhēsia) relates to the triad of truth, power and subjectification. The second traces how the theme of parrhēsia is implicit in the younger Foucault’s studies of sovereignty and discipline. The third part examines the development of new concepts of power, especially that of governmentality and the later break with power-knowledge. While the main purchase of the book is the argument about political theory – a most welcome contribution – its value starts to diminish as soon as Bang moves to being a Foucault scholar.

What ties all of Foucault writings together, claims Bang, is a ‘big’ narrative about the political. Or rather, Bang wants to show how the concept of political authority is Foucault’s ‘hidden hand’ (4) although, according to him, Foucault never explicitly conceptualised this. He claims that what ‘Foucault is taking for granted is political authority as a necessary, but certainly not sufficient, condition of societal existence’ (89). This is a strange assessment of an intellectual that was placed in a particular school of theory – namely, the historical epistemology of Gaston Bachelard and Georges Canguilhem, whose starting premise was that to thought nothing is given – and who stressed the necessity of historicism, nominalism and nihilism when studying the history of thought.

On that note, it is surprising that although parrhēsia should be so central to Foucault’s authorship, Bang makes almost no effort to develop the concept or to situate it in its proper historical context (other central concepts that are – quite annoyingly – left undefined are ‘truth’ and ‘problematization’). Lectures at the Collège de France, ‘The Government of Self and Others’ and ‘The Courage of Truth’, as well as those given at the University of Berkeley in 1983, all spend a great deal of time fleshing out the various conceptions of parrhēsia particular to Greco-Roman antiquity. Yet, Bang hardly makes reference to these, and only states in the introduction that ‘parrhesiatic political authority […] is about having the courage, in the face of all immediate risks and opposition, to tell laypeople in their political communities the truth about what has to be done’ (6-7). Not only are there only scattered hints for the reader to piece together, but the author also misses the point that Foucault was not trying to come up with a new theory of democracy or parrhēsia – he was studying how these had been constituted as problems in ancient Greek thought and practice.

The main problem that the argument of the book seems to face is one of history, an aspect of Foucault that Bang oddly enough ignores. Arguably parrhēsia, as an integral part of democracy today, runs into the same problems that Plato diagnosed – it cannot produce truth (or government by truth), only hegemony. If anyone, Donald Trump represents the figure of the bad parrhésiast who does not care for the truth and as his opposite, Edward Snowden, who confronted the public with uncomfortable ones, only to be faced with a political power that does not abide by the parrhēsiatic contract and thereby prosecuted him. To Plato, the problem was clear: the relationship between politics and philosophy needed to be reconstituted. Rather than an antagonistic democracy where speakers confront the demos, true-discourse was directed towards the prince’s soul. Bang’s proposed solution of an emphasis on ‘good parrhēsia’ therefore seems a bit naïve: who is going to roll the dice?

The book also exemplifies an unusual degree of hermeneutics of suspicion, looking for deep hidden meanings in Foucault’s writings to make the pieces fit together. Most widely, the insistence on parrhēsia – a word that does not show up in any of his published works, only the lectures – as being a theme throughout Foucault’s authorship can seem a bit stretched at times; it is perhaps rather a rationalisation and appropriation of Foucault for Bang’s own purposes.

Rather than situating the lectures on parrhēsia in relation to the problem of politics and the political – although they no doubt have a great deal to say about it, as Bang shows – it might be better to read them alongside the problem of the impossibility of the subject to speak the truth by itself under the conditions of modernity and capitalism. Thus, rather than authority, the theme would be difference: more specifically, to think differently.

It was to this aspect that the practice of parrhēsia can serve as a model, as an ethics of differentiation: parrhēsia is exactly about how the introduction of something new is possible in the old. It is a question of how truth could be produced differently, of finding the right attitude of philosophy in relation to politics. Politics and the political (as modes of thought) have never been able to produce anything new; it is the same spirals of violence, the curved lines of representation and the ever spinning wheel of Fortuna – the mere habitual repetition of concepts, to put it in Deleuzian terms. What, then, are the ways in which societies have dealt with the introduction of new thought into politics? What is at stake is exactly the relationship between politics and philosophy – ‘the critical work the thought brings to bear on itself’ (History of Sexuality II, 9). Thus, when it comes to our present, the more Foucauldian or genealogical question would be: how did it become possible to think of the political as a realm of human thought and action where the possibility of truth has become unthinkable? The lectures on parrhēsia then stand out as a suggestion that things could be otherwise – truth and politics can be co-constitutive – but there is a specific history leading up to their present enmity that displaces their old Greco-Roman unity, which is exactly what Bang seems to ignore.

Andreas Aagaard Nøhr is a PhD Student in the department of International Relations at LSE and editor of Millennium: Journal of International Studies, vol. 44. Read more by Andreas Aagaard Nøhr.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.