In How Soon is Now? From Personal Initiation to Global Transformation, Daniel Pinchbeck presents his argument for the need for urgent transformations at both the personal and global scale if we are to tackle the ‘hard problems’ posed by climate change and other pressing environmental issues. While querying aspects of Pinchbeck’s argument and the transition movement more broadly, Jason Hickel nonetheless welcomes this as a brave and necessary book from an important contemporary thinker.

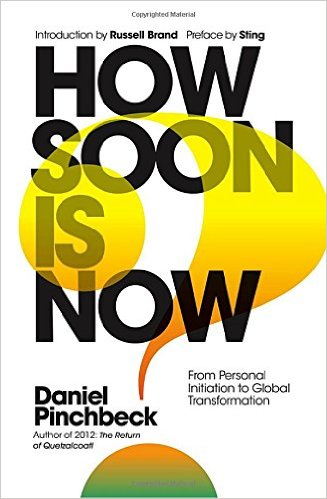

How Soon is Now? From Personal Initiation to Global Transformation. Daniel Pinchbeck. Watkins. 2017.

Our civilisation is in the throes of multiple, interlocking crises. Over the past 60 years, half our planet’s tropical forests have been destroyed, and by 2050 most of the rest will be gone. 40 per cent of our agricultural topsoil is seriously degraded, and scientists expect that continuing degradation will cause farming yields to collapse within our lifetime. Fish stocks are rapidly disappearing. Species are becoming extinct at a rate faster than any time in the past 66 million years. And we’re presently on track for around four degrees of global warming – with catastrophic consequences – even with the emissions reductions promised under the Paris agreement.

Our civilisation is in the throes of multiple, interlocking crises. Over the past 60 years, half our planet’s tropical forests have been destroyed, and by 2050 most of the rest will be gone. 40 per cent of our agricultural topsoil is seriously degraded, and scientists expect that continuing degradation will cause farming yields to collapse within our lifetime. Fish stocks are rapidly disappearing. Species are becoming extinct at a rate faster than any time in the past 66 million years. And we’re presently on track for around four degrees of global warming – with catastrophic consequences – even with the emissions reductions promised under the Paris agreement.

In light of all this, I’m always a bit surprised by how little urgency I sense out there. It’s not that the writers who fill the pages of our newspapers and books are unaware of the magnitude of these crises: the science is hard to avoid. But people seem to feel that it’s somehow unbecoming to sound the alarm with any immediacy. Nobody wants to appear panicked or unreasonable, after all. And so the veneer of calm sophistication persists, with a few gentle reformist suggestions offered here and there – nothing too disruptive to our cellophane status quo.

There are, of course, a few voices out there that buck this trend. Daniel Pinchbeck is one of them. His new book How Soon is Now? From Personal Initiation to Global Transformation ruptures through the fog with energy and passion. It offers a readable account of the hard limits we’re bumping up against, reviewing the state of knowledge on climate change, arctic methane, ocean acidification, land use and many other pressing ecological issues.

What are the solutions to these crises? Pinchbeck is, refreshingly, not persuaded by those who claim that we can avert disaster without making any substantial changes to our lifestyles or the way our economy works. On the contrary, he cuts straight to the chase: the problem is our economic operating system itself, with its reliance on ever-increasing consumption and its addiction to exponential growth.

Pinchbeck is no luddite. He is excited about rapid gains in solar technology and eager for new ideas like the ‘energy internet’, algae-based fuel and cold fusion – and his enthusiasm for these innovations is infectious. But he recognises that technology alone won’t save us. Even if we somehow manage to harness cheap, clean, unlimited energy, we would still proceed to ‘rapidly exhaust our resources, plundering the last fish from the deep in the oceans, pulling out the remaining raw material buried deep in the Earth’. To really stop our destructive momentum, he writes, we need to make a rapid transition to a de-growth model or a steady-state system.

Image Credit: (Steve Johnson CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: (Steve Johnson CC BY 2.0)

How Soon is Now? is packed with ideas for how to make this transition happen. We get punchy primers on regenerative farming, permaculture, the localisation movement and the importance of shifting away from meat consumption, for instance. In a chapter on the money system (which, being based on interest-bearing debt, has a destructive growth imperative built into it), Pinchbeck explores alternatives like cryptocurrencies, time banks and demurrage. Recognising that policymakers are unlikely to organise a total system overhaul, he hopes these piecemeal alternatives – which are already being practised – will gradually catch on to the point of rendering our current system obsolete.

For Pinchbeck, these practical alternatives are only part of the solution, however. More importantly, he says, we need an evolutionary leap in our collective consciousness. We need to shift from the dualism of Western thought, which posits a fundamental distinction between subject and object, humans and nature – the deep logic of our destructive economics – and move toward a philosophy of interconnection and interdependence. To illustrate what he means, Pinchbeck draws on his own personal narrative of moving from ‘secular materialism’ to a worldview of more mystical dimensions, aided in no small part by psychedelic substances like peyote, iboga, mushrooms and ayahuasca.

Most people who follow the transition movement, for lack of a better term, have probably noticed that psychedelics are back in fashion. I first heard about ayahuasca a few years ago, when it was still relatively unknown. Today it seems ubiquitous. Many, like Pinchbeck, hail ayahuasca and other psychedelics as crucial medicines for our time – a way to help us recognise and transcend the logic of capitalist culture. And they recruit the insights of ‘indigenous wisdom’ toward this end as well, especially from those groups that have a long tradition of working with psychedelics for shamanic purposes.

As an anthropologist, I agree that there’s a great deal we can draw from indigenous conceptions of the world, many of which reject human-nature dualisms. I think that people who see the world as characterised by relatedness and unity are able to grasp crucial truths that Western science tends to miss. Those who claim the mantle of ‘civilisation’ denigrate such people as ‘animists’, but learning – or remembering – their insights may well prove crucial to our salvation. In this sense, I agree with Pinchbeck wholeheartedly. That said, I do worry about how ‘indigenous tribes’ get represented in the discourse of the transition movement. Too often they are lumped together as though they’re all the same, and they are generally cast as timeless and unchanging in their beliefs and practices – as if they have no history. Such representations risk sliding into a kind of orientalism.

Then there is sexuality. ‘We have inherited a restricted model of romantic and erotic love,’ Pinchbeck writes. ‘Most people still believe that monogamy is the only way to find enduring happiness […] But humans are not naturally monogamous, and the current system forces many people to act hypocritically.’ Then his strong claim: ‘the planetary mega-crisis is directly related to the problems we confront as a species in this area of love and sexuality.’ Drawing on Dieter Duhm’s manifesto, Terra Nova, and observations from Tamara, the free-love commune in southern Portugal, Pinchbeck argues that overcoming the jealousy and possessiveness of monogamous love is essential to achieving true liberation.

I don’t deny that there is truth to this. But this vision of sexual authenticity rests on the assumption – peddled by some evolutionary biologists – that polyamory is the ‘natural’ form of sexuality for humans, hardwired into us over millennia. Most anthropologists reject this notion. Humans may not be naturally monogamous, but they are not ‘naturally’ anything else either. Expressions of sexuality and erotic desire – to say nothing of love – are always cultural; there is no ‘authentic’ sexuality that exists somehow outside of culture, no desire antecedent to language. Not even in Tamara. As Slavoj Žižek has put it: ‘There is nothing spontaneous, nothing natural, about human desires. Our desires are artificial. We have to be taught to desire.’

These are not indictments of Pinchbeck’s book so much as cautionary observations about certain strands of thinking within the transition movement. For anyone interested in considering how we got into this mess and how we can get out of it, How Soon is Now? will not disappoint. It takes readers on a journey through radical thought spanning Carl Jung and Hannah Arendt, Jack Kerouac and James Lovelock, Murray Bookchin and Buckminster Fuller. Even Pope Francis gets some attention. Pinchbeck is an important thinker of our time, and his is a brave and necessary book.

Dr Jason Hickel is an anthropologist at the London School of Economics and the author of Democracy as Death: The Moral Order of Anti-Liberal Politics in South Africa (University of California Press, 2015). In addition to his academic research, Jason writes regularly for The Guardian and Al Jazeera. Read more by Jason Hickel.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

“While querying aspects of Pinchbeck’s argument and the transition movement more broadly, Jason Hickel nonetheless welcomes this as a brave and necessary book from an important contemporary thinker.”

Among various notes sounded in this book, as orchestrated under its author’s baton – sounds like one is an attempt to paint Homo sapiens as ‘naturally’ polygamous – or, ‘polyamorous’ (in this interesting promotional idiom of reference).

For some reason – (all the acid I did back in the 1960s? – having a flashback?) – one recalls Margaret Mead’s attempt to ‘discover’ how atrociously repressive and sexually puritanical western society and standards are. How convenient her native informants, from whom she elicited the ‘evidence’ i.e. stories, quoted remarks, statements attributed (to one informant, in particular) – were so far away from her readership, unavailable to confirm her ‘version of events’ – in case anyone wasn’t so sure.

As Mead’s informants ‘could not be reached for comment’ – so her indictment by cross-cultural implication, passed off as comparison – turns out to have been a bit … dubious based on Samoans who recalled her visit to their island decades later.

In the context of the 20th century’s thoroughly modern, progressive sociopolitical project of trying to ‘engineer a more perfect society, and reinvent ourselves in our own perfected self-image’ – from Margaret Sanger and the contraception crusade, to sexologists (like Money, Masters & Johnson etc) etc etc – ultimately the ‘sexual revolution’ of the 1960s – Mead became a pop icon and folk hero of the zeitgeist. Hailed as ‘brave’ and so on, just like the above review does Pinchbeck’s redux of that ol’ rodeo dough.

By the 1960s, Mead had made her mark among that era’s chattering classes in the USA – soon to spawn daytime talk tv shows (Phil Donahue etc) she became a celebrity – the only anthropologist ever to achieve ‘Household Name’ status, popular recognition.

Mead based her promotion of ‘free love’ (making her the darling of a certain interest out there) – by availing of an ‘exotic’ culture – safely unfamiliar to her readership, that she could posture as the sole authority for our edification. Nobody, especially her captivated popular readership – knew anything about cultures in the S. Pacific, any different from whatever she claimed.

In the process of her ‘brave and necessary’ exposition, alas. Mead not only painted a psychosexually bizarre picture of the ‘model culture’ she studied. She ended up making a fiasco of anthropology – when key indications in evidence emerged, only decades later. Especially – comments by Samoans. Asked about their culture – some recalled Mead’s visit and their considerable displeasure, feeling they’d been exploited – upon learning exactly what Mead had claimed about their traditions and reputation as a culture – all for the edification of the intrigued – however uncritically so – reader.

Especially in terms of Mead’s core ‘message’ – the indictment by default of modern western society, as sexually puritanical and pathologically repressive – evidence upon which Mead’s claims staked out on the ‘easy sleazy sexually easy’ Samoan culture – was fatally flawed at best, and at worst – deceptive whether as a matter of self-delusion or deliberate deceit – propaganda or ‘spinformation’ – doctoring the documentation as ‘necessary.’

Really surprising to see a review like this – lip service to ‘questioning’ this book’s microwaved rehash of such fodder – coming from one who ought to know better (one would think, if one – dared) – an anthropologist at the London School of Economics (!).

The unmasking of Mead’s ‘sexual liberation campaign’ ethnography – in terms of its acceptance and popular gushing acclaim as gospel truth by and for the 1960s – didn’t come until the 1970s/1980s – too late. That was the same era in which Castaneda’s ‘Don Juan put on’ at UCLA. Castaneda was awarded a doctoral degree for a completely fraudulent ‘field work’ by his committee professors – anthropologists all, and professionals. What plausible deniability do PhD specialists in anthropology have for aiding and abetting the demolition of their own discipline’s foundations of credibility?

Mead’s popular audience was also targeted by Castaneda. General readers have a better alibi for ‘not knowing any better’ than to swallow such malarkey whole. But it seems Mead didn’t fool all of the people all of the time – even before her muddled methodology was exposed. By some indications, her ethnography of a polyamorous society was more astutely perceived – if only by a few – as Mead’s psychodrama (mirroring society). One of my faves is one from 1965, that aired in USA on ABC-TV – called OUTER LIMITS: COUNTERWEIGHT. Using a fictional name Mead serves as model for the character of – the celebrity anthropologist lady all cool (so sophisticated etc) – who, as the story unfolds – ends up undergoing a psychosexual melt-down.