In A Persistent Revolution: History, Nationalism and Politics in Mexico since 1968, Randal Sheppard explores the major political transformations in Mexico since 1968 through the prism of Mexican revolutionary nationalism to show how nationalist mythology surrounding the revolutionary state has been used to bolster both the elite and growing opposition movements. Sheppard astutely demonstrates the complexities of the post-1968 Mexican context, offering an excellent snapshot of a ‘persistent revolution’, writes Myriam Lamrani.

This book review has been translated into Spanish by Narendra Bhalla, Gabrielle Henrot, María Francisca Navega and Josephine Siou (Spanish LN785, teacher Esteban Lozano) as part of the LSE Reviews in Translation project, a collaboration between LSE Language Centre and LSE Review of Books. Please scroll down to read this translation or click here.

A Persistent Revolution. History, Nationalism and Politics in Mexico since 1968. Randal Sheppard. University of New Mexico Press. 2016.

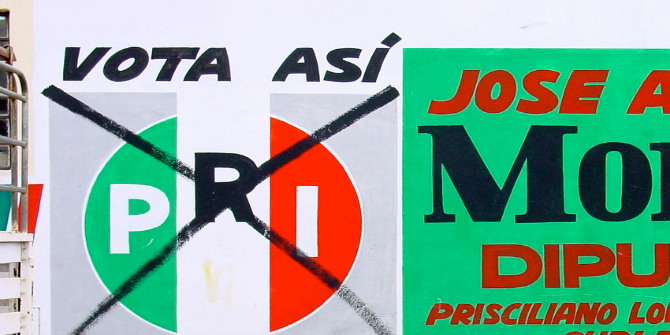

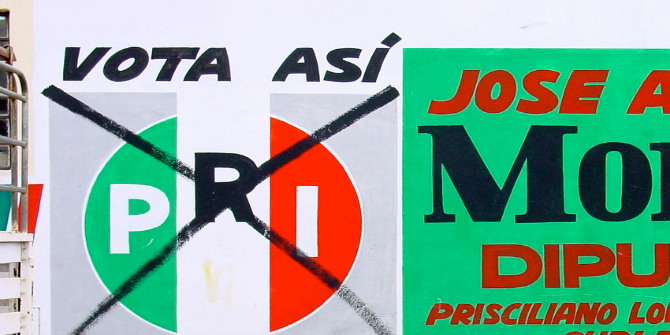

In 1990, Mario Vargas Llosa said: ‘Mexico is the perfect dictatorship.’ The Peruvian Nobel prize-winning writer was explicitly referring to the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), the ruling party that had been in power over the preceding 61 years. In his account of the post-1968 period in Mexico, A Persistent Revolution: History, Nationalism and Politics in Mexico since 1968, Randal Sheppard describes how this political colossus – now back on the political stage since the 2012 elections – ended up having clay feet.

In 1990, Mario Vargas Llosa said: ‘Mexico is the perfect dictatorship.’ The Peruvian Nobel prize-winning writer was explicitly referring to the PRI (Institutional Revolutionary Party), the ruling party that had been in power over the preceding 61 years. In his account of the post-1968 period in Mexico, A Persistent Revolution: History, Nationalism and Politics in Mexico since 1968, Randal Sheppard describes how this political colossus – now back on the political stage since the 2012 elections – ended up having clay feet.

Through a series of historical ‘snapshots’, Sheppard skilfully weaves a narrative of the slow dismantling of the Mexican state and the rise of non-elite political opposition. This shines a light on a gallery of key historical moments and revolutionary symbols prominent in the post-1968 Mexican context. From Emiliano Zapata to Benito Juárez, Sheppard examines the ways in which the political elite represented by the PRI was effectively weakened by a growing opposition movement that made use of the same nationalist revolutionary mythology to undermine the ruling political elite. The ‘Ariadne’s thread’ of this exploration of Mexican identity is precisely the nationalist mythology surrounding the revolutionary state.

The story unfolds through six main sections, each focusing on a specific historical period. Starting the book in Mexico City on 2 October 1968 with the massacre of student protesters by security forces, Sheppard introduces his topic with an event that has been mythologised in Mexico as a symbol of the PRI’s hegemony. Instead, the author argues that the Tlatelolco massacre ‘symbolised a historical rupture’ (23). It was to become a revisionist myth that would serve both the Mexican right and left. Sheppard takes this as his entry point into an exploration of Mexican national identity through the lens of revolutionary nationalism as the country came to experience a neoliberal turn. From there, he goes methodically through the successive presidential administrations, while also describing the appropriation of revolutionary cultural elements by non-elite opposition and grassroots movements.

Image Credit: (Darij and Ana CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: (Darij and Ana CC BY 2.0)

In Chapter Two, Sheppard explores the de La Madrid administration (1982-88). Symbolising a technocratic turn for the country, this was marked by the increased use of revolutionary imagery to link the government’s neoliberal turn to the ideals of the Revolution, most notably by exploiting the portrait of revolutionary leader Zapata. Chapter Three provides an enthralling description of the rise of civil society consciousness through the emergence of social movements and political opposition in the 1980s by pointing out another important rupture between the nation and the state: the 1985 Mexico City earthquake, which killed more than 10,000 people and left hundreds of thousands wounded or homeless.

The PRI government’s inept response was heavily criticised for leaving thousands of citizens organising rescue operations for themselves. Adding to the disgrace, the PRI was held responsible for the collapse of poorly constructed public buildings, thereby hinting at the party’s corruption in the aftermath of the quake, as a strong political opposition led by the PAN (National Action Party) and the Catholic Church emerged. Sheppard argues that this event facilitated an atomisation of the opposition which – and this is the core of his argument – made use of the same democratic rhetoric and symbols of the Revolution that had been endorsed by the PRI. Chapters Four and Five then take us through the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and the subsequent rise of the neo-Zapatistas in the jungle of Chiapas.

Culminating with the end of the PRI’s political hegemony in 2000 and the ensuing twelve years of PAN rule, the author concludes an intelligent discussion on the ‘complicated relationship between nationalism, politics, and culture in Mexico’ (18) in creating a Mexican identity that bridges the nation and the state. A Persistent Revolution delivers a fresh outlook on the cultural dynamics woven into post-revolutionary nationalism and historical continuity. It also brings to mind the concept of ‘eternal return’ (sensu Eliade 1949), or the idea that the power of things resides in their origins being enacted in Mexican political rituals around the myth of the Revolution.

If anything is lacking in this book, it is a thorough account of the PRI’s return in 2012 following twelve years of PAN rule. Under the Peña Nieto administration, the PRI state has been at the heart of corruption scandals, including the disappearance of the 43 students from the Rural Teachers College of Ayotzinapa. This further revealed the collusion between political parties, social movements and non-state actors, such as Mexican criminal syndicates, while seething anger at the Mexican political elite has once again harnessed civil society.

Nonetheless, the key strength of this book is its engagement with the anthropological literature on Mexico and nationalism, thus providing a clear vision on the reappropriation of revolutionary nationalist symbols to ‘contest and shape power relations’ (256), while also preserving historical continuity and the mythology of the Mexican state. Indeed, it is an ambitious task to tackle the concept of identity in Mexico, and this anthropological outlook is much welcome. The result is a portrait that emphasises the eerie resonance between Zapata, the ‘modernisation project’ under the Salinas administration (1988-94), and the EZLN (Zapatista Army of National Liberation) hailing from the state of Chiapas to wage war against the Mexican government.

In the end, Sheppard goes beyond the usual clichés by including Mexican national heroes such as Benito Juárez and Miguel Hidalgo that are ‘more relevant to Mexicans themselves’ (17). He seeks to dispel the widely held illusion that it was Subcomandante Marcos that defeated the PRI in 2000, whereas in fact it was the Catholic conservative executive, Vicente Fox (2000-06), the man that would inherit the Mexican presidency during one of the bloodiest wars in Mexico’s recent history. In an astute way, Sheppard ends up showing both the Mexican revolutionary mytho-history and our own mythology about Mexico. For anyone eager to grasp the complexities of Mexican political and cultural history through the lens of revolutionary nationalism, this book is an excellent and enjoyable ‘snapshot’ of what is indeed a ‘persistent revolution’.

Myriam Lamrani holds a BA in Art History and Archaeology – specialisation in Mesoamerica (ULB, Belgium) – and an MSc in Social Anthropology (UCL). She is currently a PhD candidate in Anthropology at University College London. Her research focuses on the role of the image in politics and popular religion in post-revolutionary Mexico. She is funded by the ERC and is part of the Making Selves, Making Revolutions: Comparatives Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics project (CARP), led by Martin Holbraad (UCL).

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

En Una revolución persistente: historia, nacionalismo y política en México desde 1968, Randal Sheppard explora las grandes transformaciones políticas en México desde 1968, a través del prisma del nacionalismo revolucionario mexicano para mostrar cómo la mitología envolvente del estado revolucionario nacionalista fue utilizada para reforzar tanto la élite y los crecientes movimientos de oposición. Sheppard demuestra astutamente las complejidades del contexto mexicano post 1968, ofreciendo una excelente imagen de una “revolución persistente”, escribe Myriam Lamrani.

Una revolución persistente: historia, nacionalismo y política en México desde 1968. Randal Sheppard. 2018.

Review translated by Narendra Bhalla, Gabrielle Henrot, María Francisca Navega and Josephine Siou (Spanish LN785, teacher Esteban Lozano).

Review translated by Narendra Bhalla, Gabrielle Henrot, María Francisca Navega and Josephine Siou (Spanish LN785, teacher Esteban Lozano).

En 1990, Mario Vargas Llosa dijo: “México es la dictadura perfecta”. El escritor peruano, laureado con el Nobel, estaba refiriéndose explícitamente al PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional), el partido gobernante en el poder durante los últimos 61 años. En su explicación del período post 1968 en México, Una revolución persistente: historia, nacionalismo y política en México desde 1968, Randal Sheppard describe cómo este coloso político – ahora de regreso en la escena política desde las elecciones de 2012 – ha terminado teniendo pies de arcilla.

A través de una serie de “imágenes” históricas, Sheppard entreteje hábilmente una historia del lento desmantelamiento del estado mexicano y el ascenso de la oposición política no elitista. Esto arroja luz sobre una colección de momentos históricos clave y símbolos revolucionarios prominentes en el contexto mexicano post 1968. Desde Emiliano Zapata a Benito Juárez, Sheppard examina las diferentes formas en que la élite política representada por el PRI se debilitó de manera efectiva por un movimiento de oposición en crecimiento, que hizo uso de la misma simbología mitológica revolucionaria para debilitar la élite política gobernante. El “hilo de Ariadne” de esta exploración de la identidad mexicana es precisamente la mitología nacionalista circundante del estado revolucionario.

La historia se despliega a través de 6 partes, cada una centrada en una época histórica concreta. El libro empieza en México City, el 2 de octubre de 1968, con la masacre de los estudiantes manifestantes por las fuerzas de seguridad. Sheppard introduce su tema con un caso que fue mitificado en México como un símbolo de la hegemonía del PRI. En cambio, el autor afirma que la masacre de Tlatelolco “simboliza una ruptura histórica” (23). Llegaría a ser un mito revisionista que serviría tanto a la derecha como la izquierda mexicana. Sheppard se sirve de este caso como punto de partida para explorar la identidad nacional mexicana a través del cristal del nacionalismo revolucionario, cuando el país llegó a experimentar un giro neoliberal. Desde allí, el autor repasa metódicamente las sucesivas administraciones presidenciales y a la vez describe la apropiación de elementos culturales revolucionarios por la oposición no elitista y los movimientos populares.

Image Credit: (Darij and Ana CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: (Darij and Ana CC BY 2.0)

En el capítulo dos, Sheppard explora la administración de La Madrid (1982-88). Para simbolizar una vuelta tecnocrática en el país y conectar el giro del gobierno neoliberal con los ideales de la Revolución, la administración usó imágenes revolucionarias, particularmente el retrato del líder revolucionario Zapata. El capítulo tres ofrece una fascinante descripción del auge de la conciencia de la sociedad civil, a través de movimientos sociales y oposición política en los años 80, señalando una ruptura importante entre la nación y el estado: el terremoto de 1985 en México City, en el que murieron 10000 personas y dejó a cientos de miles heridos o sin hogar.

La inepta respuesta del gobierno PRI fue duramente criticada por dejar a miles de ciudadanos organizando operaciones de rescate por sí mismos. Para más vergüenza, el PRI era considerado responsable del derrumbe de edificios mal construidos, insinuándose así la corrupción del partido en el periodo que siguió al terremoto, a medida que surgía una oposición política muy fuerte liderada por el PAN (Partido Acción Nacional) y la Iglesia Católica. Sheppard argumenta que ese evento facilitó la atomización de la oposición que -y este es el meollo de su razonamiento- hizo uso de la misma retórica democrática y símbolos de la Revolución que habían sido respaldados por el PRI. Luego los capítulos cuatro y cinco nos conducen por la firma del Acuerdo Norteamericano de Libre Comercio (NAFTA) y el subsiguiente aumento de los neo-Zapatistas en la selva de Chiapas. Desembocando en el fin de la hegemonía política del PRI en el 2000 y los consiguientes doce años bajo el dominio del PRI, el autor concluye con una discusión inteligente sobre la `relación complicada entre nacionalismo, política y cultura en México´ (18) creando una identidad mexicana que conecta la nación y el estado. Una Revolución Continua da una nueva perspectiva de la dinámica cultural entrelazando nacionalismo post revolucionario y continuidad histórica. Esto también trae a la mente el concepto de `eterno retorno´ (sensu Eliade 1949), o la idea de que el poder de las cosas reside en la promulgación de sus orígenes en rituales políticos mexicanos alrededor del mito de la Revolución.

Si en este libro falta algo, es una descripción detallada del regreso de PRI en 2012 después de doce años del gobierno de PAN. Bajo de la administración de Peña Nieto, el gobierno del PRI ha estado en el centro de los escándalos de corrupción, incluyendo la desaparición de los 43 estudiantes del Colegio de Docentes Rurales de Ayotzinapa. Esto reveló además la confabulación entre los partidos políticos, los movimientos sociales y los actores no estatales, como las organizaciones criminales mexicanas, mientras que la rabia acumulada contra la elite política mexicana ha unido una vez más a la sociedad civil.

No obstante, el punto fuerte de este libro es su compromiso con la literatura antropológica sobre México y el nacionalismo, proporcionando así una visión clara sobre la reapropiación de los símbolos nacionalistas revolucionarios para “contestar y moldear las relaciones de poder” (256), a la vez preservando la continuidad histórica y la mitología del estado mexicano. De hecho, abordar el concepto de identidad en México es una tarea ambiciosa y esta perspectiva antropológica es muy bienvenida. El resultado es un retrato que enfatiza la inquietante resonancia entre Zapata, el ‘proyecto de modernización’ bajo la administración Salinas (1988-94), y el EZLN (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) proveniente del estado de Chiapas para emprender la guerra contra el gobierno mexicano.

Al final, Sheppard va más allá de los clichés habituales al incluir héroes nacionales mexicanos como Benito Juárez y Miguel Hidalgo que son “más relevantes para los propios mexicanos” (17). El autor busca disipar la ilusión ampliamente difundida de que fue el Subcomandante Marcos el que derrotó al PRI en 2000, de hecho, en cambio, fue el ejecutivo conservador católico Vicente Fox (2000-06), el hombre que heredaría la presidencia mexicana durante una de las guerras más sangrientas en la historia reciente de México. De una forma astuta, Sheppard termina mostrando tanto la mito-historia revolucionaria mexicana como nuestra propia mitología sobre México. Para quien quiera comprender las complejidades de la historia política y cultural mexicana a través de la lente del nacionalismo revolucionario, este libro es una excelente y agradable instantánea de lo que en realidad es una “revolución persistente”.

Myriam Lamrani es licenciada en Historia y Arqueología (BA en Art History and Archaeology – especializada en Mesoamérica (ULB, Belgium) – y Antropología Social (UCL). Está llevando a cabo sus estudios de doctorado en Antropología en UCL (University College London). Sus investigaciones se centran en el papel de la imagen en la política y la religión popular en el Mexico post revolucionario. Esta becada por el ERC forma parte del proyecto Making Selves, Making Revolutions: Comparatives Anthropologies of Revolutionary Politics (CARP), liderado por Martin Holbraad (UCL).

Nota: Esta reseña ofrece los puntos vista del autor, y no las posiciones del blog de LSE Review of Books, o de LSE, London School of Economics.

“He seeks to dispel the widely held illusion that it was Subcomandante Marcos that defeated the PRI in 2000…”

As a Mexican, I’d never heard of this. What is the evidence there’s this ‘widely held illusion’? Marcos could not have defeated the PRI because the government was not toppled by the Zapatista movement, nor was Marcos running for office. Even those not sympathising with the PAN recognise it was Fox’s presidency what ended the PRI rule in 2000 (“el cambio”).

Many thanks for your comment Ernesto. The sentence that you singled out relates to one of the claims of the author (p. 18) which I understand as being part of this ‘mythologising’ of Mexican post-revolutionary politics, so in fact this is not to be taken literally. Sheppard is addressing the perception of the events taking place in the late 90s from afar and how, the possible association of Subcomandante Marcos with the toppling of the PRI could seemingly appear to be related. Hope this clarifies his point.