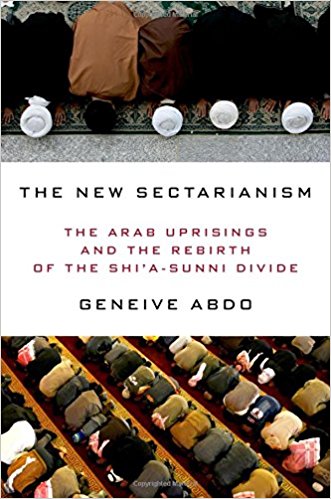

In The New Sectarianism: The Arab Uprisings and the Rebirth of the Shi’a-Sunni Divide, Geneive Abdo argues that growing tensions between Sunni and Shi’a Islam have become the primary conflict and challenge within the Middle East. While Abdo’s analysis of social media discourse is original, Nagothu Naresh Kumar fundamentally questions the book’s reliance on a primordialist understanding of sectarian conflict in the region.

The New Sectarianism: The Arab Uprisings and the Rebirth of the Shi’a-Sunni Divide. Geneive Abdo. Oxford University Press. 2016.

A primary debate that animates sectarianism in the Middle East is its etiology. While some scholars seek to place it in the realm of modernity and look for its origins in geopolitics, realpolitik and modern state practices, others bestow it an ancient heritage. Theoretically, these inclinations can be distilled as instrumentalist and primordialist approaches respectively. The primordial prism, prominent in policy, diplomatic and media circles, argues that age-old animosities animate the contemporary conflicts between Sunnis and Shias. In this view, the conflict reaches back to the seventh century and early Islamic history plays a prominent role. Geneive Abdo’s book, The New Sectarianism: The Arab Uprisings and the Rebirth of the Shi’a-Sunni Divide, tries to walk a tightrope between the two, but is easily tempted to side with primordialism.

Western analysis and thought, according to Abdo, do not apportion due importance to religion as a causal factor in the Arab world in spite of experiencing Islamism for three decades, and instead look through the default political prism of the nation state. For her, these two aspects interact with one another to produce distortion and policy oversights and prevent ‘fruitful interaction between East and West’ (9). Ultimately, for Abdo, religion as a causal heavyweight stands on its own without recourse to other variables such as the economy. It is no more an epiphenomenal aspect when it comes to explaining the region (146).

Throughout the book, sectarianism is thus used as a category of analysis and as an explanatory device. This conceptual leap is crucial for it seeks to walk over the instrumentalist approach that prizes materialism: instrumentalists are wary of employing a sectarian prism and see it as a political construct that is malleable for manipulation by elites.

Abdo does not discount the argument that conflicts in the region are due to the weakening of the state or to the Iraq war of 2003. However, for her, one of the fundamental reasons for violence lies in the reimagining of Islam by various actors. Such refashionings, usually comprising an uncompromising stance, lead to others being deemed unbelievers. For Abdo, the region’s future is imprinted with sectarian strife because these are ultimately questions about doctrines and thus, by extension, irreconcilable, making conflict inevitable. Likewise, all geopolitical concerns and issues may either wither away or transform, but not sectarian issues. Islam is a special case, for since its incipient days it has witnessed unresolved questions about authority and legitimacy. The book also makes the argument that sectarianism in the region is an ever-present threat with a timeless quality to it (149). Sectarianism in the Middle East is therefore an unremitting leviathan in waiting, ready to burst onto the stage with fervour through only a slight nudge.

Image Credit: (Marcu loachim CCO)

Image Credit: (Marcu loachim CCO)

According to Abdo, the series of changes brought about politically for the Shias in the Arab world sows insecurity and ‘even fears of extinction’ among the Sunnis, which demands them to combat the threat (13). From her analysis of the tweets of figures such as clerics and sheiks, which betray a pronounced rancour between Sunnis and Shias, Abdo claims that the primeval strife between the two sects is just being recast in the contemporary scene. However, the analysis of these tweets and their layers of virtual vitriol on Twitter belies an analytic preference for those in power. Thus, questions of power and authority go unexamined in the book.

Of course, the current conflicts in the Middle East likewise cannot be explained away by taking recourse solely to geopolitics. They are grounded in formidable Islamic political theology. Contemporary Jihadi ideology similarly depicts Shias as apostates and also excludes certain Sunni communities for not living up to their strictures. Ibn Taymiyyah and Abd al Wahhab and their doctrinal enunciations are influential among contemporary jihadists, and ‘othering’ can function as a top-down process to become part of the social strata. An example would be Saudi Arabia’s curriculum that denigrates everyone except those who subscribe to Wahhabism. Contemporary Salafist and Wahhabi discourses also oppose the Shias on two fronts – firstly, Shia practices of venerating different figures implicate them as mushrikin or polytheists. Secondly, since the Shia steadfastly do not acknowledge the rectitude of the Prophet’s companions and successors, they are dubbed as rejectionists and thus as a threat to Sunni believers.

Nonetheless, the book’s central claim that religion as a variable in comprehending the Middle East has been given short shrift does not hold under close examination. The region, in fact, is seen typically as a hotbed of sectarianism, religion and illiberal passions. This is also evident in the over-emphasis and palpable fixation on Islam, Muslims, Muslim religiosity and Muslim women. Islamic Piety, in other words, stands as a substitute for the region, and any incongruities that do not fit into these categories are relegated analytically, which in turn expunges the histories and agency of non-Muslims, non-Muslim Arabs and other communities.

Ironically, the association of sectarianism with the Middle East is also problematic for it assumes, negatively so, that the region is religious, and more so than any other region when juxtaposed with its counterparts such as the ‘secular’ West. This conjunction of Muslim religiosity is invariably evident in the collocation ‘Muslim World’, which Abdo uses uncritically across the book (51, 65, 86).

To privilege sectarianism as a social and political category therefore obfuscates more than it reveals and has little analytical purchase. Religion may be called on to bear the causal weight, but its complexities, such as other modes of sociality and relationality, are conveniently ignored in the book in favour of stable, ossified categories and reifications.

Sectarianism as a category also projects a monolithic picture of Shias across the Middle East, wherein Shia groups that do not follow Twelver Shiism (prominent in Iran) are clubbed together due to their geopolitical positions. Even within the Shia, there are fissures, such as how the Khomeini doctrine of Velayat-e faqih (clerical power that goes against the grain of authority and exercise of power in Shiism) horrifies Shia clerics in Iraq as well as Iran. It also reduces complex theological differences to catchy terms.

The book’s primordialism furthermore ignores overlapping alliances and associations. For example, it does not unravel the alliance between Iran, Hamas, Hezbollah and Syria. There is invariably a critical need to take sectarianism seriously without relying on established essences or explaining it as a function of something else altogether. The book will certainly be profitable to those who look at how social media discourses function in the Middle East and how these, in turn, shape perceptions that have tangible effects. However, despite the original analysis of tweets and snippets from clerics and sheiks, the book has less to offer when it comes to understanding sectarianism today.

Nagothu Naresh Kumar holds an MPhil from JNU, New Delhi, with research interests in religion and global politics, intellectual history and anthropology of religion. Read more by Nagothu Naresh Kumar.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book: