When it comes to academic writing, words matter – but do we overly tame and narrow the meanings and reach of the terms we use? In this feature essay, Charlotte Wegener and Ninna Meier invite readers to think about words that are important to their own research and twist them, squeeze them – perhaps even risk overdoing them – to see how this might prompt new perspectives or unexpected insights. Below Wegener picks a fight with her own topic word ‘innovation’ and reflects on the limitations of ‘hedging’ when it comes to academic writing.

This essay is part of a series examining the material cultures of academic research, reading and writing. If you would like to contribute to the series, please contact the Managing Editor of LSE Review of Books, Dr Rosemary Deller, at lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk.

Word Matters, Words Matter: On Fine-Tuning our Vocabularies of Academic Writing to become Better Writers

Image Credit: (Steve Johnson CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: (Steve Johnson CC BY 2.0)

‘Word matters’ means word issues, word stuff, thinking about what words can do and what we can do with words. ‘Words matter’ means that we must select carefully which to use, dig into them, investigate their connotations and possible usages. Written words are our primary communication tools and many key words in the humanities and social sciences are tricky, ambiguous and open to interpretation. Some words, such as democracy and freedom, are even called floating or empty signifiers. Their meaning is unstable and can be used for a variety of purposes.

We have been preoccupied with word and writing matters for years. Initially, each of our research subjects – public innovation, leadership and management – sparked our concerns. These concepts refer to activities in abundance and have been defined in an over-abundance of ways. They will never be tamed and narrowed down to one single, unambiguous meaning. Many research traditions encourage us to take control of words. The kind of fine-tuning we address here points in the opposite direction. Rather, we want to play with key words of our research to see what we can do with them and what they do to us. We seek a vocabulary that allows for various sources of insight into what it means to be human, to be a researcher and to be a writer. To further a scholarly field, we need to experiment with and even transgress traditional vocabularies in order to make innovative and impactful contributions. We need to sharpen our sensibility towards what we can do with words, try our their metaphorical power and even add new meaning to them.

In doing this, we have been inspired by Milan Kundera’s ‘Sixty-Three Words’, a chapter in The Art of the Novel (1988). Here he shares the 63 words that make up the dictionary of his novels: his key words, his problem words, the words he loves. We invite you to explore word matters with us because words matter. Write a blog post about your favourite word, a word that keeps annoying you, a word that slips through your fingers no matter what you do to control it. Choose a word that is important in your research and twist it, squeeze it, overdo it or connect it with other words in brand new formations. We have experienced how doing this provides for new insight into our research fields, for unexpected perspectives and for novel modes of writing (Meier and Wegener, 2017; Glăveanu, Tanggaard and Wegener, 2016).

Below, from her favourite writing space at the kitchen table, Charlotte tells the story of getting into a fight with her topic word ‘innovation’, discovering an addictive use of hedges and how she recovered through radical un-hedging and finally finished the text.

On Innovation and ‘Hedging’

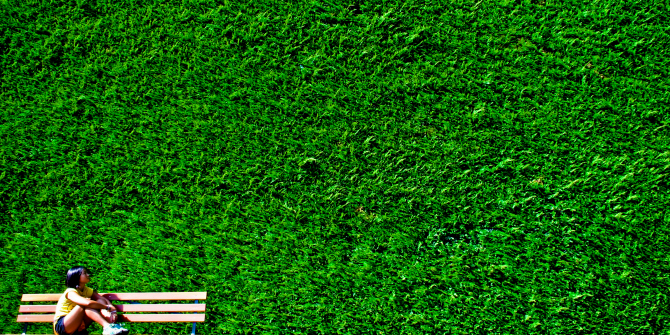

Image Credit: (Mish Sukharev CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: (Mish Sukharev CC BY 2.0)

The morning sun is caught by the prism in my kitchen window. Myriad rainbow spots are sprawled over the white wall, and some have even escaped to the white-painted panels in the hall through the open door as if they have decided to elope from the group. Today I have an insistent voice in my head telling me I will not be writing something of either quality or interest. It paralyses me when someone, anyone, asks me to write something specific. Write that funny incident! Write that review! Write analytically. Write about innovation (my main research subject).

I can’t.

My texts have to evolve from the inside (not my inside, the inside of the text itself). Or sideways, obliquely. Rebelliously, surprisingly. I like my texts to surprise me, as the science fiction writer Ray Bradbury once said.

I have recently tried to write about innovation within a defined frame, and although I made the frame myself, I was bored and severely restricted. I felt I had nothing to say about innovation that wasn’t already said. I couldn’t even write something I believed in myself. I wrote because I had a book contract and a deadline, and it was indeed deadly. The more restricted I felt, the more I discovered that I couldn’t just write what innovation is, what this innovation agenda is all about and the ways in which we can make innovation happen. I was so sorry and frustrated: I wished to tear apart the arguments about innovation for growth and global competition. I wanted to strangle the word ‘innovation’. I wanted to get rid of it and tell the readers: here are my stories, here are my worries, my jokes, go find out your own truths. I have nothing more to offer, but don’t go for innovation in order to unleash ‘your inner entrepreneur’ or ‘build capacity for global competition’. All idea generation workshops, the best version of you and your company and the global market in its entirety – ‘stick ‘em where the sun don’t shine, all right?’, as horror writer Stephen King so beautifully said about ‘all those messages and those morals’.

Slowly, slowly, I discovered ways to write. I wrote about jazz improvisation and the sweet spot (where the fresh and the familiar come together perfectly); I stepped back and dissected the notion of ‘a problem’; I wrote a chapter about innovation metaphors and mused over their ordinariness – a light-bulb popping out of a brain, cogwheels, smiling stick figures or post-it notes in bright colours on walls. Innovation metaphors are certainly not innovative: how come? I rounded off the manuscript with a scene from a conference where I was supposed to talk about innovation and ended up talking about resonance, heavily assisted by young men playing jazz music for the audience just before my lecture. I caught a poetic moment of the musicians, the audience and me being in complete sync. I knew that no matter the reviews, this was the final scene of my book.

When the third or fourth version of the manuscript finally made it through the (patient and kind) editor and went out to external review, I got it back with some of the best critique I have ever received. The reviewer liked my stories, the overall idea and the fresh perspectives. But he was really annoyed by all those ‘hedges’ – didn’t I really stand up for anything I said? As I started revising, I discovered dozens and dozens of: could it be that… we might consider… this is a fact and yet, it is wrong too.

It had become a tic. The tic of a persona slippery as an eel.

What is a hedge? It is all the nice rhetorical devices used to cover my ass, celebrated in research because we learn to protect ourselves so as to make it on the global market of apolitical, impersonal, non-risky research. You can take an academic writing course and learn when to hedge and why, but I have never heard of any course offering help to un-hedge. The more afraid we are, the more we can couch our claims in cautious and tentative language. Hedging is supposed to make statements as accurate as our evidence supports. But how accurate is may, might, should, would, appear, suppose, seem, tend, likely, potentially, probably, possibly, perhaps, hypothetically, presumably, generally, usually, occasionally…??

In business, a hedge is an investment position used to minimise substantial loss, but also substantial gain. Investopedia explains that ‘hedging’ is analogous to taking out an insurance policy:

If you own a home in a flood-prone area, you will want to protect that asset from the risk of flooding – to hedge it, in other words – by taking out flood insurance. There is a risk-reward tradeoff inherent in hedging; while it reduces potential risk, it also chips away at potential gains. Put simply, hedging isn’t free.

Hedging isn’t free. Think about that.

Publishing our research is indeed like owning a home in a flood-prone area! But taking an authoritative stance and writing what we know and what we believe is true without taking out insurance for each and every claim are worth the risk.

I took the hedges out. All of them. I envisioned discharged hedges piling up in my recycle bin, a huge hedge-pile in the dark. By eliminating each and every hedge, I turned into a transparent broker of ideas and opinions. I filtered and focused. I became the prism catching the sun, pointing the reader’s attention not to my insurance and to irreproachable me, but to myriad rainbow spots on a kitchen wall.

Charlotte Wegener is Associate Professor at Department of Communication, at Aalborg University. Ninna Meier is Associate Professor at Department of Sociology and Social Work, at Aalborg University. They have been co-authors and writing friends since their doctoral studies. Since then, they have written about and explored writing in several ways. They seek to expand academic writing as both process and product, for instance by involving other modes of expression such as fiction, music, blog posts, dreams and standup to mention but a few. Specifically, they aim to make academic knowledge production more democratic, open and fun. Read more by Charlotte and by Ninna.

This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.