In The Origin of Others, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature Toni Morrison extends her existing nuanced explorations and interrogations of race and racism by examining the structures that construct ‘Otherness’ in the interconnected contexts of literature and lived experience. Based on a series of lectures given at Harvard University in 2016, this is not always an easy or accessible read, but Samantha Fu praises it as a powerful riposte to the persistence of bigotry, intolerance and division today.

The Origin of Others. Toni Morrison. Harvard University Press. 2017.

As a Pulitzer Prize-winning author and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature, Toni Morrison needs no introduction. Readers of Morrison’s work will be familiar with her nuanced exploration of race through the stories of African American, predominantly female characters. In The Origin of Others, her first work of non-fiction in almost a decade, Morrison examines the structures and strictures of ‘Otherness’ within the context of literature and lived experience, and in so doing exposes race as a figment of our ‘genetic imagination’.

Discrimination, Morrison begins by reminding us, is a social construct. ‘How does one become a racist, a sexist? Since no one is born a racist and there is no fetal predisposition to sexism, one learns Othering not by lecture or instruction but by example.’ As exemplification, Morrison offers up a 1955 short story by Flannery O’Connor, in which a white man attempts to educate his nephew in the process of ‘Othering’. The story concludes with uncle and nephew gazing together at the statue of a black jockey, feeling their differences dissolving, each believing himself to have acquired respectability through the common identification of an ‘Other’.

Morrison argues that this process – the invention of an ‘Other’ – is an age-old formula that has at its core the illusion of power and the need for control. Nowhere is this more evident than in accounts of slavery in America. Morrison details scenes of repulsive violence from both memoirs and fiction, in which slave owners are driven to exhaustion by the severity of the punishments they inflict. She remarks that it was almost as if they were shouting ‘I am not a beast! I’m not a beast! I torture the helpless to prove I am not weak,’ and concludes that ‘the necessity of rendering the slave a foreign species appears to be a desperate attempt to confirm one’s own self as normal’.

But such attempts to define the ‘estranged’ self are futile, she writes, because:

There are no strangers. There are only versions of ourselves, many of which we have not embraced, most of which we wish to protect ourselves from. For the stranger is not foreign, she is random; not alien but remembered; and it is the randomness of the encounter with our already known – although unacknowledged – selves that summons a ripple of alarm.

This uneasiness with ‘Others’ extends beyond African Americans; accordingly Morrison does not limit her reckoning to slavery and the black condition. In the wake of mass immigration in the twentieth century, she observes that ‘the cultural mechanics of becoming American [were] clearly understood’:

A citizen of Italy or Russia emigrates to the United States. She keeps much or some of the language and customs of her home country. But if she wishes to be American – to be known as such and to actually belong – she must become a thing unimaginable in her home country: she must become white.

In Morrison’s view, much of the alarm caused by the ongoing migrant crisis is fostered by our uneasy relationship with our own foreignness and our rapidly disintegrating sense of belonging, both of which can be alternately reinforced or diminished by literature. While she acknowledges the danger in sympathising with the stranger – the possibility of being seen as a stranger oneself – she argues that in creating and maintaining false constructs of ‘Otherness’, we deny them their personhood and ‘the specific individuality we insist upon for ourselves’. This concept of individuality is one Morrison has repeatedly addressed in her own works of fiction. ‘They shoot the white girl first’, goes the opening line of her 1997 novel Paradise, ‘with the rest they can take their time’. But the white girl is never identified, thus forcing the reader to engage with each character on the basis of her individual traits rather than through racial stereotypes.

Underlying Morrison’s examination of both her own work and that of others is the implicit admonishment that it is past time authors moved beyond ‘the color fetish’ and ‘romancing slavery’ to grapple with the ways in which literature buttresses notions of ‘Otherness’. After all, ‘the resources available to us for benign access to each other, for vaulting the mere blue air that separates us, are few but powerful: language, image, and experience.’ And what is literature, if not language, image and experience? Throughout, The Origin of Others makes a strong case for setting aside our routine and easy portrayals of race to instead embrace the opportunity that narrative fiction provides ‘to be and to become the Other’.

But though compact, The Origin of Others is by no means a universally accessible read. As a compilation of a series of Norton lectures delivered at Harvard in 2016, the book’s origins are evident in long blocks of quotations and dense digressions, which perhaps lend themselves more to verbal expression than to the written word. At times, the volume can also read like a justification of Morrison’s past work (‘my effort may not be admired by or be interesting to other black authors [… who] may wonder if I am engaged in literary white-washing. I am not’), which perhaps reflects her own experience of ‘Otherness’ as a black female author in a predominantly white- and male-dominated world. But despite these limitations, The Origin of Others is nonetheless a timely examination of the persistence of bigotry and intolerance in a world where black lives seemingly continue to matter less, where white supremacists are applauded and elected to public office and where migrant children are left for dead for no crime except that of being an ‘Other’. In it, Morrison manages to serve up a powerful reminder that ‘race is the classification of a species, and we are the human race, period’.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Amendment: The title of the Flannery O’Connor short story was removed from the original review due to its use of a racial slur.

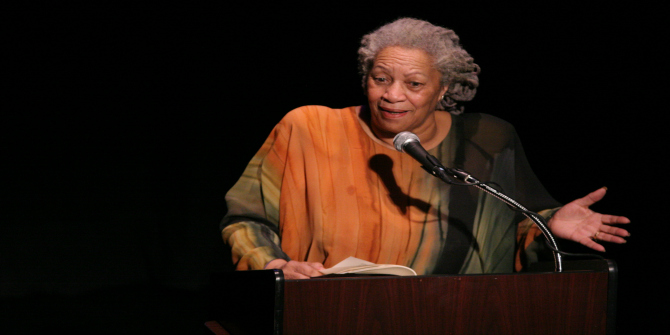

Image Credit: Toni Morrison speaking at ‘A Tribute to Chinua Achebe: 50 Years Anniversary of Things Fall Apart‘, 2008, New York (Angela Radulescu CC BY SA 2.0).

Find this book:

Find this book:

3 Comments