In Colonial Captivity during the First World War: Internment and the Fall of the German Empire, 1914-1919, Mahon Murphy offers a comprehensive study of the experiences of the 20,000 Germans in colonies who spent in time in Allied captivity during World War One. This is an impressive analysis that uses internment as a prism to examine the War’s extra-European theatres, underscoring the conflict’s global dimensions and critically examining imperial notions of race, writes Joshua Smeltzer.

Colonial Captivity during the First World War: Internment and the Fall of the German Empire, 1914-1919. Mahon Murphy. Cambridge University Press. 2018.

Over the course of World War One, approximately 20,000 Germans in colonies from German South-West Africa to Togo, from Samoa to Tsingtao, spent time in Allied captivity. Mahon Murphy’s Colonial Captivity during the First World War: Internment and the Fall of the German Empire, 1914-1919 is an impressive study of their experiences, using internment as a ‘prism through which to analyse the extra-European theatres of the First World War’ (17). In the process, Murphy provides an expansive narrative, covering a number of geographically disparate camps and thereby connecting colonies to the battlefields in Europe.

Murphy draws on a wide range of primary sources in English, German, French and Japanese to underline the extent to which the Great War was a global war. The threat of reprisals among European powers encapsulates this theme: the poor treatment of German captives by British forces in the colonies could lead to reciprocal measures being taken against British captives by German authorities on the Western front. The result, Murphy tells us, was that ‘the escalating waves of reprisals […] played a significant role in disfiguring the Great War and linked the colonial sphere of the war directly to the battlefields of Europe’ (6). Indeed, one of the accomplishments of Murphy’s study is to demonstrate that ‘internment in one colony did not operate in isolation but was part of the web of a global camp system’ (36).

The second part of Murphy’s monograph focuses on German internees’ experiences in the colonial camps, which he analyses in terms of a number of social axes: lives in the camp depended not only on the contingencies of the specific camp, but also the class, gender and race of the individual. Thus, we learn that German officers were often interned in separate camps away from enlisted soldiers; that women were considered ‘the embodiment of would be Deutschtum (“Germanness”) in Africa’ and were therefore ‘expected to provide a moral example for young adventurous men who were said to lose their morals once separated from Europe’ (112-13); and that the treatment of German Askari – African auxiliary troops used by the Germans – was largely mediated by British concerns regarding their own ‘imperial image’ and ‘postwar concerns for the establishment of British influence in the former German colonies’ (119). However, for the British Foreign Office, one thing was certain: ‘A German is a German, whether a missionary or soldier, and as such will always be tempted to give the enemy (his own people) what assistance he can, so long as detection is difficult’ (99).

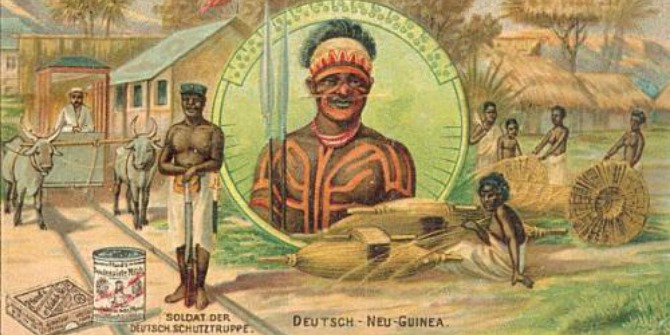

Image Credit: German and Askari soldiers in German East Africa, 1914 (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R19361 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Image Credit: German and Askari soldiers in German East Africa, 1914 (Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-R19361 / CC-BY-SA 3.0)

Indeed, race and racial hierarchy cut across Murphy’s monograph as a recurring theme. One of the immediate effects of the war was the breakdown of narratives of ‘the common European civilizing mission’ in favour of ‘nationalist imperialism’ (37). No longer was there a clear dividing line between the ‘civilized’ European and the ‘barbarian’ indigenous other; rather, ‘in the extra-European theatre both captor and captured moved away from a common European identity in the colonies towards separate national identities’ (94). Thus, Germans came to occupy an inferior position in comparison to their white European counterparts, but they were still seen as higher than non-Europeans. The conditions of German captives in Samoa, then under the control of the New Zealand authorities, is particularly illuminating in this regard: ‘those who lived outside the main settlements were even allowed to carry revolvers to protect themselves rather than having a European family “placed at the mercy of the Chinese”’ (73).

On the other hand, Murphy stresses that the racial dimensions of empire featured heavily in German wartime propaganda directed against the British and the French. This particular sub-genre of propaganda played on ‘imagery of racial savagery and mutilation’ and appropriated ‘ready-made imagery of colonial violence’ to argue that ‘the British […] had betrayed the common Christian civilizing mission’ (125-26). These texts were designed to fuel anxieties that German settlers were being subjected to the authority of colonial troops, stripped of the superior position they claimed as a result of their race. Similar to ‘Black Shame’ propaganda following the use of African soldiers in the Allied occupation of the Rhineland, these texts pointed to a fear of the ‘“barbaric” colonial soldier’, which was mobilised in both the European and extra-European theatres (140). As a result, the colonial imaginary proved to be just as global and interconnected as the physical camps themselves.

The book ends by considering the repatriation of Germans from the colonies, both during the war and after the signing of the Armistice agreement. At the outbreak of World War One, the British swiftly repatriated Germans from Cameroon and Togo, while transferring combatants and males of military age to camps in Britain. This formed Britain’s ‘ideal strategy’ for handling internees (184). However, Murphy shows that a decisive shift took place in repatriating German internees after the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915: unrestricted submarine warfare created shipping shortages and led to the prioritisation of military goals over the transportation of German citizens. Thus, as Prime Minister H. H. Asquith declared the week after the Lusitania incident, military-aged German males would be kept ‘in existing circumstances, prima facie […] for their own safety, and that of the community, be segregated and interned, or, if over military age, repatriated’ (185). Their repatriation would thus be delayed until the end of the war.

For many Germans in the colonies, repatriation and internment meant a loss of private property with little chance of eventual recovery. Murphy shows that even after the end of the war, Germans were largely prevented from returning to the colonies out of a fear that their return would, following the words of a British War Cabinet memorandum of 1919, create ‘grave internal disorder and possibly bloodshed’ in the colonies (200). Stuck in the Weimar Republic, repatriated Germans felt alienated by the Germany they encountered upon their return, with one noting his ‘[horror] at the prospect of suffrage for women’ (204). Their vision of Germany and Germanness – mediated by their experiences in the colonies – no longer seemed to correspond to the world around them.

Aside from a number of minor typographical errors throughout the text, this is an impressive study of the global dimensions of the Great War through the lens of internment. Indeed, Murphy’s narrative firmly establishes an interconnected web of camps, implicated in imperial notions of race and shaped by a common European civilising mission. While setting a global scope, Colonial Captivity still remains unified by its focus on the German experience of internment.

Joshua Smeltzer is a doctoral student at the University of Cambridge pursuing a PhD in Politics and International Studies, with a focus on twentieth-century German political thought. Read more by Joshua Smeltzer.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book:

1 Comments