In Remembering Women’s Activism, Sharon Crozier-De Rosa and Vera Mackie explore the memorialisation of women’s activism, drawing on case studies from Anglophone and Asia-Pacific contexts. Partly a feminist history, partly a study of memory, this intricate analysis not only offers interesting insight into how women have worked to improve society and the ways this has been remembered, but also the implied question of how such figures and those now stepping to the forefront will be remembered—and misremembered—in years to come, writes Bethan Johnson.

This review is part of a theme week published in the run-up to International Women’s Day 2019 (#IWD2019) to showcase and celebrate women’s scholarship across the social sciences and humanities. You can explore more of the week’s content here.

Remembering Women’s Activism. Sharon Crozier-De Rosa and Vera Mackie. Routledge. 2018.

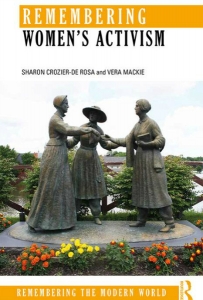

‘History and memory are gendered’ (1), claim authors Sharon Crozier-De Rosa and Vera Mackie in the opening lines of their new book, Remembering Women’s Activism. Part of a larger Remembering the Modern World series published by Routledge, the authors dissect the intricate interweaving of gender and history in their study of women’s engagement with activism and its memorialisation. Partly a feminist history, partly a study of memory, the book uses mnemonic sites (memorials, archives, statues, street names, museums) to evaluate the roles women have been shown to play in the making of the modern world.

After establishing its parameters in a brief introduction, the book tackles the topic of women’s activism and how it has been remembered through four thematic chapters—focused respectively on suffragettes; nationalist revolutionaries; female labour advocates; and, finally, on ‘grandmothers’ (women more commonly known as ‘comfort women’)—before concluding with a section on the future of female activism and its memorialisation. Each of the chapters includes a comparative element, as campaigns and activists from various countries are considered and then contrasted.

In the suffrage chapter, Crozier-De Rosa and Mackie compare how the suffrage movements in the US, the UK and Australia developed and succeeded in their aims for universal suffrage, as well as the acts and reputations of specific suffragettes, such as Emmeline Pankhurst, Millicent Fawcett and Susan B Anthony. Having charted these women’s deeds, some militant and others less so, in the name of suffrage, the authors chart their memorialisation through analysis of the various museums, exhibits, statues and archives that have sought to preserve and retell the story of suffrage campaigning. By showing the precarity of archives such as The Women’s Library, the designs and placements of statues that depoliticise or ‘domesticate’ more militant activists and the couching of many suffragist artefacts in poorly contextualised exhibits, the authors effectively demonstrate how much modern, popular understandings of the suffrage movement have been moulded to serve more palatable narratives about how women garnered the vote and, relating to militant suffragettes in particular, how female activists organise and campaign.

The chapter discussing female revolutionary nationalists take as its examples Qiu Jin of China (1875-1907) and Constance Markievicz of Ireland (1868-1927). Crozier-De Rosa and Mackie consider how Markievicz’s place in the history of Irish republicanism, as a powerful campaigner for a unified Ireland as well as her work in elected positions, has always been intimately linked to her status as a wealthy woman. The authors explain how Markievicz’s reputation became increasingly tarnished, along with that of many other Irish revolutionary women, by accusations of sexual impropriety, cowardice and feminine flightiness. By analysing the designs and placements of statues of her, the authors likewise illuminate how there have been attempts in some regions to soften her image. Markievicz, it is rightly shown, has proven to be a sort of Rorschach test for onlookers, whereby people of various regional, political and gendered identities advance a different narrative about her based on their own predilections.

Image Credit: Statue of Qiu Jin, Shaoxing, China (猫猫的日记本 CC BY SA 3.0)

Image Credit: Statue of Qiu Jin, Shaoxing, China (猫猫的日记本 CC BY SA 3.0)

Qiu Jin’s reputation, the authors argue, has also gone through varying degrees of alteration over the course of regime changes in China. With Qiu Jin beheaded for her role in attempting to overthrow the Qing dynasty, Crozier-De Rosa and Mackie trace the roots of her radical thinking and militancy through her well-educated childhood, her time in exile among revolutionary thinkers in Japan, to her plotting the uprising as she led a local girls’ school and published a radical women’s journal. The authors then compare this with Qiu Jin’s turbulent memorialisation, whereby she has been buried and reburied almost a dozen times. While largely ignored during Mao’s lifetime, they show how she has more recently been adopted as a laudable heroine by numerous factions in Chinese politics who seek to appropriate her revolutionary spirit to further their criticisms of ‘Old China’.

Using a triadic approach, the chapter on female labour activism focuses not on specific women who altered policies, but rather on industrial accidents and strikes that galvanised reforms, specifically the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in New York City in 1911 (which killed 123 women and 23 men), the Tomioka Silk Mill strikes in Japan in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries and the Rana Plaza building collapse in 2013 (which killed more than 1,100 workers). The chapter discusses how the hardships and sometimes deaths of women working in these sites motivated politicians and members of society to reform workplace safety regulations. Emotional accounts of female suffering are evidenced as being particularly influential in gaining reform, and have likewise endured to inform how these workers are remembered.

Finally, the chapter on ‘grandmothers’ and the politics of sexual violence in war includes a brief exploration of activism regarding ANZAC Day, before turning to the memorialisation of women who faced sexual slavery during the Second World War by Japanese military personnel. The chapter describes how, for more than two decades, weekly protests each Wednesday outside of the Japanese embassy in Seoul have not only inspired similar activism elsewhere, but also placed pressure on government officials to recognise and respond to survivors’ and activists’ objectives, such as attaining an official apology and reparations. The authors note how pressure from activism such as this has influenced international relations in the latter half of the twentieth century. As the most well-known mnemonic site on this issue, the chapter devotes considerable time to the statue placed on the square where this protest is held in Seoul, its artistic interpretation and replications in other places around the world.

In the foreword by the series editors, Remembering Women’s Activism is described as being aimed at ‘students, scholars, and general readers of contemporary history’ (xii): while perhaps slightly too generalist and brief to advance the understanding of scholars whose expertise is on any of the given examples, the work certainly provides students and non-specialists ample insights, as well as an array of useful literature to further their studies through the book’s extensive endnotes. The book is particularly successful in its ability to happily marry sections devoted to providing background information on an activist or event with how they have been memorialised.

Crozier-De Rosa and Mackie also do a commendable job elucidating the intricacies of archives, museums and exhibitions as well as the designing of statues for readers. The fiscal politics of memory are acknowledged—particularly regarding how funding decisions influence who is memorialised and how—and serious thought is given to how various styles of presentation subconsciously influence how the public is introduced to these women. For those interested in remembrance history or students learning about archives for the first time, this element of the work is invaluable.

Perhaps the most subtly impressive element of the book may be Crozier-De Rosa and Mackie’s sustained, somewhat underlying, message about the augmentation of women’s places in history when left to men, be they in politics or in academia. Throughout, examples are given of how female activists’ legacies are diminished, or their sharp edges smoothed away, by the memorials influential men have created for them. On numerous occasions, the authors mention when female activists worked to create their own memorials, and this effectively implies that more work should be done contemporaneously by women activists to prepare their work for memorialisation so as to avoid misrepresentation.

Illuminating in many regards, Remembering Women’s Activism nevertheless suffers slightly by some obscurity in its methodology and by its almost teleological concluding section. The book discusses an array of issues that galvanised women throughout the modern era, but Crozier-De Rosa and Mackie never reveal their justification for choosing the movements featured in the book. Campaigns regarding reproductive rights (be that access to birth control or abortions), pay equity and temperance, for example, are well-known sites of female activism, and yet find no place in this narrative. Moreover, in the introduction, the authors note that their featured examples will be from Anglophone or Asia-Pacific regions. The authors are careful to provide a balance of examples from the featured regions, but they fail to justify why they selected the areas they use. In doing so, questions regarding the universality of their claims about how women’s history has been altered by the male gaze and about the comparability of these two localities arise. While a book about women’s activism need not cover every movement around the world bolstered by women, it does behove authors to justify what compels them to tell certain stories and not others.

Crozier-De Rosa and Mackie show a sustained engagement with the politics through which their readers will approach this book. The work even concludes on the line: ‘As we have demonstrated above, putting the history of women’s activism on record can provide resources for future political campaigns’ (210). Following references at various points in the text to the current state of gendered politics, their concluding chapter ‘Marching On’ pays particular attention to the Women’s March, first organised in 2016, coupling it with developments in feminist activism such as #MeToo, centenary celebrations of female suffrage and the fact that women currently hold high office in countries such as Germany, Myanmar and Japan.

As the rest of the book reflects, there is no unidirectional path in women’s activism, though, and developments in the months since the book’s publication complicate the impression given that there is a new wave of female activism making forward progress towards gender equity. The 2018 American midterm elections saw the election of more women than ever before, and #MeToo has emboldened many new conversations around the world about the treatment of women in society. However, at the same time, in the final weeks of 2018 attempts were made to dissolve a South Korean foundation for comfort women, and in the early weeks of 2019 accusations of antisemitism levelled against Women’s March organisers saw the Democratic National Committee and many other partners withdraw support from the event and crowd numbers shrink.

Nevertheless, pervasive in the conclusion and the rest of Remembering Women’s Activism are not only interesting insights into how women have worked to improve society and the ways that work has been remembered, but also the implied question of how such figures and those now stepping to the forefront will be remembered—and misremembered—in years to come.

Bethan Johnson is a doctoral candidate in the Faculty of History at the University of Cambridge. Her doctoral research explores the rise of militant separatist groups in Western Europe and North America in the mid-Cold War-era. The work explores the life-cycle of violent ethno-nationalism, driving forces behind radicalisation along separatist lines and authoritative methods for ending and avoiding deadly conflicts. Her master’s dissertation, also undertaken at the University of Cambridge, studied the manipulation of cultural nationalism for political unionist purposes by Lady Llanover in nineteenth-century Wales.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics

Find this book:

Find this book: