In Fiber: The Coming Tech Revolution – And Why America Might Miss It, Susan Crawford explores how the political machinations of large corporations in the US have reduced the impetus to invest in fibre infrastructure, with a potentially detrimental effect not only on US competitiveness and innovation, but also on public health, education and community access to resources. This is a meticulously researched and accessible account of the development and implications of fibre optic technologies, writes Courteney J. O’Connor.

Fiber: The Coming Tech Revolution – And Why America Might Miss It. Susan Crawford. Yale University Press. 2018.

Susan Crawford introduces Fiber: The Coming Tech Revolution with an anecdotal story about a trip to South Korea during which she truly started to understand the revolution of fibre optic connections and networks. I admit to being surprised at the feats of connectivity Crawford describes and the extensive fibre network that is already operating in places such as South Korea: interactive holographic technology and augmented reality were available (in a limited fashion) during the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang. The investment by the South Korean government of billions of dollars over the last decade has ensured that South Korea is on the cutting edge of telecommunications technologies and accustomed to the sort of high-speed, high-volume connectivity that in the United States and elsewhere still seems to be only a distant possibility.

While the US does have fibre optic cables between cities (‘long haul’ or ‘backbone’ lines, 6), and in some metropolitan areas (‘middle-mile’ lines, 6), the lines do not actually extend to customers’ premises: the fabled last mile. The political machinations of large corporations in the US have reduced the impetus and willingness to invest in fibre infrastructure, to the potential detriment of not only the US economy but also the future competitiveness of American businesses at the international level. The future is, according to US telecommunications companies, too expensive to pay for in the present.

One of the things I find most useful about this particular book is the fact that Crawford not only makes the entire volume readable for anyone who chooses to pick it up, but she also takes the time to explain the concepts upon which the book is based (fibre optics, 5G and so on). So many authors now assume that all those reading their books have the knowledge of a subject matter expert, removing their work from the majority of the public that may be trying to educate themselves in a particular area. Not so with Crawford. Fiber is full of anecdotal remarks and segues that not only contribute to the general impact of the knowledge she is imparting, but also to the sense that this book is for everyone: this is an incredibly refreshing method of writing. For example, in explaining her visit to a fibre optic research and development facility in Chapter Two, Crawford makes the point that a single fibre optic cable can in fact ‘carry the entire weight of data on the internet’ (22). Considering she has just explained that fibre optics are literal strands of pure glass, this fact is both incredible and the best explanation I have yet come across in my research. It certainly leaves you wondering why less than 10% of the United States has fibre to the home (FTTH) services.

Image Credit: (chaitawat CCO)

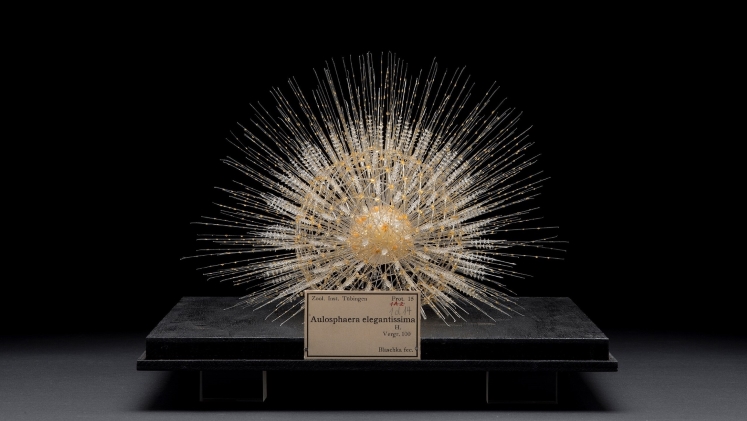

Image Credit: (chaitawat CCO)

This is one of the leading themes of Crawford’s book: the United States, considered by most to be one of the most highly developed countries in the world, known for innovation and high levels of technological uptake, has low-quality and high-cost internet. And this is, apparently, in large part thanks to cable and telephone monopolies that have no economic incentive to upgrade their services in the face of high up-front costs. In the short term, one could imagine this being difficult to explain to shareholders, but considering the rapid rate of technological innovation and diffusion, this can only hurt the American economy and international competitiveness in the long run. So why wait?

In order to maintain an international reputation as a home for innovation and also to keep its place at the forefront of technological progress, the US needs to embrace fibre optic solutions and technologies. As can be seen in Crawford’s many examples, other nations are already outstripping the US in terms of services offered, relatively low costs and the strength and speed of communications technology and access. Fibre optic technologies will reinforce and improve not just the economy in the long run; it will also positively affect public health, national education at various levels, relative inequality and community access to resources.

Collaboration between schools and universities is possible with fibre connections, allowing students at one end of the country to manipulate laboratory equipment on the other side of the country in real time (97). Rural communities that would otherwise be unable to access educational opportunities can ‘beam in’, as it were, especially given the possibilities presented by VR/AR technologies. Healthcare-in-the-home services can offer the elderly, the chronically ill and their families some peace of mind knowing that at the touch of a button, a high-quality audiovisual feed can be made between a patient and their healthcare professional without ever leaving the house (121). Fibre connectivity can introduce new educational and development opportunities in low-income neighbourhoods, allowing communities in these areas access to the sort of services that higher-income communities take for granted (136). In terms of security, there is a necessity for high speed, secure communications that do not have to operate within the bandwidth limits of today. Thus, maintaining current communications technologies rather than investing in fibre will be a significant hindrance to the future of the United States and its citizens.

As we can see, however, there are significant incentives for corporations in the US, particularly cable and telephone monopolies, not to develop fibre further, or at least not right now. Without a move for federal policy, which is itself inhibited by the interests of these corporations and monopolies, it is increasingly unlikely that fibre will get the sort of traction in the United States that it has gained elsewhere. The US will therefore continue to lag behind the more technologically enhanced (and, perhaps, technologically dependent) nations, such as South Korea.

While the US is a very good case study for the ongoing battle between corporate interest and public policy, it is by no means the only country within which these contestations are taking place. It is, perhaps, the most widely publicised case due to the sheer global reach of American mega corporations, but the fact remains that many of the points that Crawford makes in her examination of the (lack of) uptake of fibre in the US due to corporate stakes can be applied elsewhere. The politicisation of corporate interests and the value of these when determining public policy is an area that deserves further analysis and development, and Crawford adds to that body of work quite nicely with this text.

I can genuinely say that I would recommend Fiber to any number of people with an interest in the development of fibre optic technologies, particularly in relation to the United States. And while this book is US-focused, many of the lessons that Crawford communicates through her stories and easy-to-follow writing style can be applied in nonpolitical contexts. Crawford’s description of the technological innovations and application of fibre optic research and development is generally useful as well as being politically explanatory. The material is obviously meticulously researched as well as being very well-written according to a logical narrative structure (something I cannot say about every book I read in the technology and security fields). I thoroughly enjoyed this volume from start to finish and recommend it as an excellent addition to any bookshelf.

Courteney J. O’Connor is a PhD candidate with the National Security College of The Australian National University. Her research considers the securitisation of cyberspace and the development of cyber counterintelligence policy and practice.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Find this book:

Find this book:

1 Comments