In Place and Postcolonial Ecofeminism: Pakistani Women’s Literary and Cinematic Fictions, Shazia Rahman analyses how literary and cinematic creative works by Pakistani women draw connections between women and the environment and underscore the necessity of postcolonial ecofeminist theory to understanding Pakistani women’s contribution to the ecological field. This is a timely study, writes Sarah Hussain, showcasing fiction that amplifies the vital role of women when it comes to addressing the pressing global issue of environmental degradation.

Place and Postcolonial Ecofeminism: Pakistani Women’s Literary and Cinematic Fictions. Shazia Rahman. University of Nebraska Press. 2019.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Given the increasing ecological problems we are facing globally, Shazia Rahman’s book, Place and Postcolonial Ecofeminism: Pakistani Women’s Literary and Cinematic Fictions, could not have been written at a more appropriate time. Literature is a powerful tool in helping humans understand problems by awakening an emotional response, and this is pivotal, because without emotional connection, one rarely feels the need to act. Rahman is a literary critic who has written about Environmental Humanities in a number of academic journals. However, Rahman’s latest published work gives readers an opportunity to consider the severity of today’s environmental problems, and Rahman highlights how this can happen through analysing literary and cinematic fiction. Her book shows why the exploration of postcolonial ecofeminist theory is essential in order for us to value women’s contribution in the ecological field.

Rahman’s book offers an interesting perspective on postcolonial ecofeminist works as she explores the representation of Pakistani women by analysing films – Sabiha Sumar’s Khamosh Pani (2003) and Mehreen Jabbar’s Ramchand Pakistani (2008) – as well as novels – Sorayya Khan’s Noor (2006), Uzma Aslam Khan’s Trespassing (2003) and Kamila Shamsie’s Burnt Shadows (2009). Rahman (16) states that:

through fictions, women can represent both what is and what could be, the dangerous possibilities and the ideal. Fictions allow us to imagine suffering as well as joy. They help us feel empathy for others and imagine better ways to live and seek justice.

The inclusion of Pakistani women in the ecological field is often ignored as media reports associated with the region are frequently connected with terrorism while other relevant news is often overlooked, especially in the Western media. Rahman’s book focuses on the neglected visibility of women’s roles in trying to prevent ecological degradation in the region. She argues that ‘Pakistan’s women’s attachment to their environment and their environmental concerns and issues are often ignored because patriarchal discourses about Islam and religion are dominant in multiple realms’ (4). This poses a problem as women’s knowledge regarding environmental regeneration is ignored, which is a huge detriment as their specific ecological knowledge would enable everyone to be more equipped to deal with climate change.

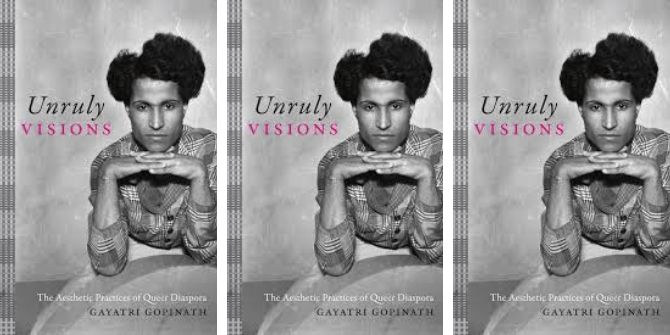

Image Credit: Champa tying a manat to a tree next to a saint’s tomb. Screenshot from Ramchand Pakistani, directed by Mehreen Jabbar, published in Place and Postcolonial Ecofeminism by Shazia Rahman and used by permission of University of Nebraska Press.

Rahman has chosen significant literature to draw attention to Pakistani women and their connection to the environment and place. The theme of ‘place’ largely informs her book, and through this theme she introduces us to the relationship between ecofeminist theory and postcolonial theory. As she states: ‘the postcolonial ecofeminism discussed in my book is an important answer to the dilemma of Pakistani intellectuals; instead of embracing religious nationalism or siding with U.S imperialism, this scholarship emphasises embracing our ecosystem and all the creatures in it while simultaneously resisting patriarchy’ (6). She believes that there should be more attention given to postcolonial Pakistani literary studies in order to address growing environmental problems.

The book emphasises how European colonialism has played a part in further oppressing both women and the environment. The analysis of Sumar’s film Khamosh Pani addresses the violence targeted at women and the environment as the film explores the 1947 partition of British India, in which Pakistan was created. Rahman highlights how the South Asian women portrayed in the film are exploited as is the environment due to the capitalist economic model. Rahman states:

since the empire has had a hand in oppressing the poor, sexual and gender minorities, non-white people, women, other species, and the environment, postcolonial theory, ecocriticism, and feminism are each equally important.

Rahman delves further into the ‘place’ theme as we are introduced to the problems associated with a human-made border. By analysing the film Ramchand Pakistani, she explores the existence of the border between India and Pakistan, which is only marked by a white cemented line. Rahman explains how ‘as with the border created by colonial powers around the world, the border between Pakistan and India does not take the local people or the environment into consideration’ (61). We see how this border further impacts women as Rahman shows us through the analysis of specific characters. Her exploration of the displacement theme draws attention to the problems associated with war and nationalism. She argues that ‘nationalism and humanism oppress human and nonhuman others when we fight wars without regard for the land and all who live there’ (141). Rahman wants her readers to consider environmental problems as a global crisis by encouraging ‘throwntogetherness’. This concept requires humans to realise that the natural earth is a shared space that we occupy and it is essential for us to negotiate this space with humans and nonhumans alike.

To further highlight how women and the environment are exploited through the destruction of landscape, Rahman explores place-based postcolonial ecofeminism as she discusses the vernacular landscape of East Bengal. By examining the cultural landscape that evolved, this gives readers a chance to reflect on how it has been shaped by social attitudes. She does this by analysing Khan’s novel Noor (2006). Rahman states that ‘reading the novel through a postcolonial ecofeminist perspective, we see that the violation of the land was commensurate with the violation of people, especially women, and true healing will only come about with the acknowledgment’ (82). Through her analysis, Rahman highlights the atrocities caused in 1971 when Bangladesh gained independence and we further recognise people’s relationship with land. The story draws attention not only to East Bengal, but to the multiple partitions in the region. Rahman argues that ‘Noor implies that attention to space-time and vernacular landscape can lead to understanding and healing from the trauma of war and violence.’

When the natural land is abused, women are primarily affected as they use the land as a means of livelihood. Through Place and Postcolonial Ecofeminism, we understand through Pakistani women’s creative work how women and the environment have been subjugated. Furthermore, we are able to appreciate the relationship between social and environmental justice. At a time when we must address climate change, it is essential to value the contribution of those women who have been primarily affected by ecological degradation and Rahman amplifies those voices by drawing our attention to significant literary and cinematic fictions of Pakistani women.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Great review that hit on the nerve. The in-depth knowledge and interconnectedness of the multitude of factors involved in this issue can only be captured and augmented by innovative and deep thinkers with natural zest such as the reviewer.

This is an important topic that should not be dealt with in a restricted area of this planet, rather it should be examined a cross all nations and boarders. Well done!