In Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics, renowned scholar Stephen Greenblatt offers an analysis of depictions of tyrannical figures in seven of the sixteenth-century playwright’s works for a fresh take on Shakespeare and our contemporary political milieu. Reviewing this multilayered testament to the value of interdisciplinary understandings of societies and governing systems, K.A. Doyle examines how the book is relevant as a lens on US politics and on social science research more broadly.

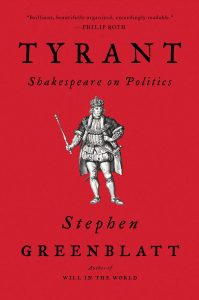

Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics. Stephen Greenblatt. Vintage. 2018.

Shakespeare and US Politics: How a 16th-century playwright’s perspective contributes to understanding the 2016 US presidential election and to social science research

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

Stephen Greenblatt’s Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics might not be high up on the reading lists of political science scholars and students. The author’s resume, while impressive, is not likely to nudge the title any higher: since 2000, Greenblatt has been the John Cogan University Professor of Humanities at Harvard University, and he specialises, to no surprise, in understanding the writings of William Shakespeare, among other offerings of modern literature and criticism. His 2011 book, The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, won the Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction. He is also credited with pioneering ‘new historicism’ – an approach to reading and interpreting literature by situating it within the political, social and cultural contexts in which it was written (and consumed).

Stephen Greenblatt’s Tyrant: Shakespeare on Politics might not be high up on the reading lists of political science scholars and students. The author’s resume, while impressive, is not likely to nudge the title any higher: since 2000, Greenblatt has been the John Cogan University Professor of Humanities at Harvard University, and he specialises, to no surprise, in understanding the writings of William Shakespeare, among other offerings of modern literature and criticism. His 2011 book, The Swerve: How the World Became Modern, won the Pulitzer Prize for Nonfiction. He is also credited with pioneering ‘new historicism’ – an approach to reading and interpreting literature by situating it within the political, social and cultural contexts in which it was written (and consumed).

So what does Greenblatt, through this compact and unfussy analysis of seven of the sixteenth-century playwright’s plays, have to say about contemporary US politics? He avoids calling out any world leaders by name, yet reckons with the current political moment throughout the book. As could be expected, there is an unevenness in the overlay onto current events, given Greenblatt’s new historicism approach and his intention to say something about authoritarianism past and future. There is less discussion of institutional norms than might be relevant to our context since it is generally monarchies under consideration in Shakespeare’s plays (not counting those based on Roman times).

Nevertheless, in examining the King Henry VI trilogy, Richard III, Macbeth, King Lear, The Winter’s Tale, Julius Caesar and Coriolanus, Greenblatt makes some contemporary parallels explicit (invoking ‘grabbing’ women when sketching a portrait of Richard III (54) and citing Russia to (literally) bring home the account of Roman warrior-hero Coriolanus’s turn to the Volscians to engage in secret dealings (178), for example) and compels the reader to frame the key points of Tyrant for a fresh take on Shakespeare and our political milieu. Although the book was published in 2018, the upcoming 2020 US presidential election encourages a timely review with an eye towards the social sciences.

Appreciating the political context in which Shakespeare was writing – Elizabethan England, under constraints on free speech against the monarch’s rule – it appears he had much to say about human psychology, but also political systems and power, explored through fictional and historical reigns from the Roman to his own contemporary era. Shakespeare turned a critical eye to the political systems and power struggles in transition to tyranny; he studied and portrayed the factors shaping this political devolution.

As demonstrated most conspicuously by Richard III, would-be tyrants are enabled to seek this extreme, concentrated and violent form of power by their own psychological frailties, or ‘psychopathology’ (55), including ‘limitless self-regard, the law-breaking, the pleasure in inflicting pain, the compulsive desire to dominate. He is pathologically narcissistic and supremely arrogant’ (53). King Lear suffered this as a later-in-life affliction. The motivations of those closest to the tyrant who also happen to hold some power, either politically, militarily, financially or familial, and the incited behaviour of the ‘crowd’ or greater society, supplement these qualities. Macbeth and Coriolanus, for example, succumbed to delusional claims to power due to provocations from their wife and mother, respectively; John Cade, lower-class but politically savvy, begins the dismantling of law and order by swaying the ‘mob’ (37) in King Henry VI, which serves the interests of the devious Duke of York.

Would-be tyrants are tactical and tactful power-grabbers but tactless governors once the power is theirs:

For the tyrant, there is remarkably little satisfaction. True, he has obtained the position to which he aspired, but the skills that enabled him to do so are not at all the same as those required to govern successfully.

And this failing will frequently tip them over into the self-destruction which was nevertheless on standby during the ascent, as Greenblatt points out in the ultimate fortunes of Richard III and Macbeth. Coriolanus never garners the votes he needs to assume consulship in Rome because his tactlessness, captured in his inability to ‘play the politician’ (176) and feign both respect for the lower classes and self-control, supersedes in the final stretch.

Finally, there isn’t a fail-proof strategy to constraining the ascent or the reign of the tyrant, much as there isn’t an orderliness or inevitable sequencings of events for the tyrant to seize power. In Julius Caesar, even when minor characters and tribunes from Murellus and Flavius to Brutus heed the warning signs of tyrannical ambitions, their judgements as to how best to quell the unravelling situation are questionable, and the outcomes of their actions are not as planned.

In fact, Greenblatt concludes that the view of Shakespeare as expressed through his plays was that ‘the best hope lay in the sheer unpredictability of collective life, its refusal to march in lockstep to any one person’s orders’ (187-188) and that ‘a popular spirit of humanity [… could never be] completely extinguished’ (189). Individuals, from the commoner to the elite, were capable of influencing events for the better, too.

Between these broad points lies myriad insights and direct and indirect commentary on US politicians, institutions and voters. Namely, a major question that reveals itself is who is letting the eventual tyrants get away with it? This is addressed in one of the most insightful passages of Tyrant. Greenblatt breaks down six ‘accessory’ types based on the plot of Richard III, which should appeal to political scientists as professional purveyors of taxonomies; although, as Greenblatt cautions:

listing the types of enablers risks missing what is most compelling about Shakespeare’s theatrical genius: not the construction of abstract categories or the calculation of degrees of complicity but the unforgettably vivid imagining of lived experience.

His classification, nevertheless, ensnares those who acquiesced passively or actively supported the emergence of the tyrant, from the (relatively) few who are genuinely convinced of the usurper’s false intentions – the so-called ‘victims’ and ‘dupes’ (66) – to the proportionally small group that marches along to, and even maybe helps orchestrate, the dangerous antics of the usurper, in the hopes that they will individually gain from the allegiance. He also captures a group that actively participates in the schemes of the tyrant, but with much broader motive than the aforementioned direct collaborators. They are most like the faceless and nameless crowd, which can be readily co-opted, the differing but flammable motivations igniting each other in something like a social tipping point.

There are some socioeconomic claims embedded in Greenblatt’s typology, but overall the different groups are not ascribed particular characteristics based on gender, race or other categories. From an interdisciplinary perspective, this section of Greenblatt’s analysis helpfully refreshes the question of how Donald Trump was elected in the 2016 US presidential race, if we associate the current president with authoritarian tendencies and assess voters as various groupings of enablers with motivations.

What led voters to cast their ballots as they did in 2016? Demographics were largely taken for granted in the lead-up to the 2016 election, and further attempts to tackle this question in the few years since the election have often solicited data on voting intentions, behaviour or outcomes from a featured subset of the population, such as white voters, those without a college degree or those with a lower socioeconomic status.

But Greenblatt’s categorisation is a reminder that segmenting the population based on these standard variables is not a sure means to understand the complexity of voting behaviour and social and emotional collectivity. His reading of the script also invites us to consider whether we should account for tyrannical ambitions playing a role in voting behaviour before the vote is cast. For example, in Peter K. Hatemi and Zoltán Fazekas’ account, both elected leaders and voters – especially in a time of populism – display narcissistic tendencies. The authors focus on the voters, arguing that Democrats and Republicans were shown to exhibit equal yet divergent narcissistic traits: those who were associated with a greater sense of entitlement were ‘[led…] away from the Democratic party’. A politician mirroring the general predisposition of narcissism and this specific angle might be a popular choice.

Many studies have documented the outsized role of racial and gender biases in the 2016 election; others show that gender biases are perpetrated by women, too. It should come as no surprise, then, that ‘demography is not destiny’, as Andrew Gelman and Julia Azari assert, even though some demographic identifiers have a measurable correlation with attitudes and voting preferences. In other words, the characteristics of the voting population that have absorbed social science research are useful but insufficient parameters for voting behaviour if we do not account for how such preferences are activated.

This is not to say that findings of sexist or racist views or that the notion of ‘cultural anxieties’ within particular voting blocs are irrelevant or immaterial; rather, the intricacies of ‘lived experience’ defy narrow research, and psychological understandings of human reactions and behaviour under conditions of rising populism and authoritarianism help expose various prejudices and economic or other uncertainties.

Tyrant is exceedingly relevant as a lens on US politics and social science research and makes a useful case, too, for incorporating interdisciplinary understanding of societies and governing systems. It is, finally, a multilayered testament to recognising the ‘political’ in our work and acting on it for the public interest, as Greenblatt and Shakespeare do by revealing, in their own ways, political forces and our agency within them.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Image by MikesPhotos from Pixabay.

1 Comments