In Libres d’obéir : Le management, du nazisme à aujourd’hui [Free to Obey : Management, from Nazism to Today], Johann Chapoutot offers a new critical history of management, arguing that current managerial thought is in part a legacy of Nazism. Focusing particularly on the influence of Reinhard Höhn, Chapoutot suggests striking parallels between Nazi approaches to management and modern managerial techniques, writes Nadia Matringe.

Libres d’obéir : Le management, du nazisme à aujourd’hui [Free to Obey : Management, from Nazism to Today]. Johann Chapoutot. Gallimard. 2020.

The Nazi roots of our managerial apparatus

The Nazi roots of our managerial apparatus

Johann Chapoutot’s new book, Libres d’obéir (Free to Obey), reveals the ‘liberalism’ at the heart of the Nazis’ conception of management (Menschenführung). The book focuses on the itinerary of Reinhard Höhn (1904-2000), one of the many technocrat intellectuals serving the Third Reich. Höhn, a lawyer by training, started his career in the Sicherheitsdienst des Reichsführers-SS (SD), the intelligence agency of the SS and Nazi Party in Germany, before becoming a general in the army. His rise in status was the result of tireless intellectual energy combined with social and tactical skills. He published various treatises on politics, public administration and military history under the Nazi regime before devoting himself to teaching and theorising business management from the 1950s onwards. The managerial thought elaborated by Höhn and his fellow Nazis relied on a form of Social Darwinism which claimed to reject the state and envisaged ‘freedom’ as the driving force underlying economic performance.

Contrary to the healthy logic of natural selection, the state, for Höhn, had a counter-selective role, since it enabled the diseased, the dreamer, the idle and the madman to prosper at the expense of the wholesome, and thus threatened the accomplishment of the Germanic race. According to this view, the state did not exist among the original Germans, organised in tribes and in families respectful of life and of the natural laws. While forest ‘Germanity’ never knew despotism or dictatorship, the emergence of the state was seen as concomitant with the racial degeneration of Ancient Rome and with the fixing of a set of abstract rules in parchment (the Justinian Code). Unlike the Jews who were seen as people ‘of the book’, the Germans were in essence bound together by an instinctive community of body and spirit that did not require any supra-natural guarantor of the commonwealth (neither the state nor the Church). The Nazis wanted rules and norms to be simplified, and bureaucracy erased. The Nazi community viewed itself as a natural and spontaneous union of free men, who obeyed themselves by obeying their leader. The Führer embodied the commandment of life itself and was chosen because he could interpret the laws of nature and decide what the German people wanted – sometimes without knowing it themselves.

In practice, state power was in competition with myriad ad hoc ‘agencies’ whose lifespan was limited to the completion of one mission for which they were given a budget and a timeline (for example, the Four Year Plan, the Organization Todt and the Reich Commissioner for the Consolidation of German Nationhood). Unlike the sclerosing state, such organs were seen to be in harmony with nature: speedy in their deliberation and flexible in implementing their mission. The state could continue to exist only to support and anticipate the natural law through the establishment of a eugenic legislation of sterilisation (and later execution) of the ‘non-performant’ (leistungsunfähige Wesen). Meanwhile, healthy Germans who worked for their community could be chemically boosted thanks to methamphetamines (prescribed en masse to workers and soldiers). The German people were tools, materials, factors of growth. The purpose was to bring about a nation united in its fight for life and against the wanderings of liberal individualism and Marxist tyranny.

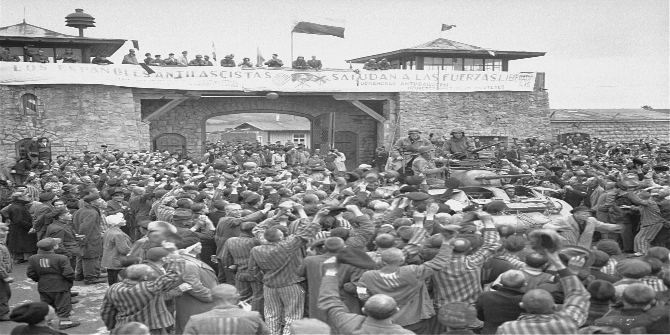

The productive effort of the Germanic ‘biomass’ required compensation. Obsessed with the risk of a political revolution, the Reich rulers bought the consent of their people through tax reductions and social benefits financed by spoliations and plunders. A management that would gratify and promise was necessary to motivate and create a productive community. ‘To each his due’ (Jedem das Seine), the horrific motto engraved on the entrance of the Buchenwald concentration camp, meant that justice was equated with the Nazis’ notion of equity (just rewarding) rather than equality.

The perspectives of upward mobility sold by Nazi bosses and glorified in movies were accompanied by an effort to promote happiness at work. ‘Strength through Joy’ (Kraft durch Freude), a Reich-wide work council, ensured the wellbeing of German workers. Millions were spent on improving the lighting and ventilation of factories and the nutrition of workers. The KdF created canteens, spaces of conviviality and libraries. It organised classical concerts in factories and developed sports and competition games. The workers were also taken care of outside the factory with hikes, cruises and all-inclusive stays at holiday resorts. Höhn was also attentive to managers’ self-development and encouraged them to take all the necessary measures to enhance their creativity (exemplified by his later 1979 book, Die Technik der geistigen Arbeit. Bewältigung der Routine, Steigerung der Kreativität [The Technique of Mental Work: Overcoming Routine, Increasing Creativity]). Thus ‘staff wellbeing’ was an integral part of Nazi managerial thought. Leisure and self-care had meaning only in relation to work: they existed to relax and recharge the productive individual and to optimise production.

Like tens of thousands of members of the old Nazi elite (academics, journalists, doctors, businesspeople), after the war Höhn put his intelligence into the service of the new ideals of economic growth and triumphant Western democracy, as the director of an industrial think tank working on efficient management techniques (Deutsche Volkswirtschaftliche Gesellschaft). The purpose was to produce American-style versatile managers as opposed to the specialised doctors and engineers that had dominated German business since the rule of the last German Emperor and King of Prussia, Guillaume II (1888-1918). A German version of the Harvard Business School (also replicated in France with INSEAD in 1957) was inaugurated by the DVG in Bad Harzburg in 1956. Students were practitioners sent by their employers to undergo a short period of training.

The ideal of management Höhn taught at the school was inspired by the reformers of the Prussian army who had devised a ‘mission tactic’ (Auftragstaktik) – itself inspired by Napoleon – after defeat in the Battle of Jena in 1806. This tactic consisted in giving general orders confined to certain objectives (e.g. take hold of this hill before dusk); soldiers were then free to choose the best means to reach the target. Such a margin of autonomy heightened the soldiers’ sense of responsibility. Failure to succeed denoted personal deficiency.

Höhn transposed the Auftragstaktik to business with his ‘management via delegation’, supposedly anti-authoritarian and thus suited to the new democratic culture. Unlike before, bosses were not supposed to prescribe a specific course of action up to the most precise details of its execution. They assigned a goal and a time delay, and then observed, evaluated and controlled the workers’ response. The Nazi system of ‘co-management’ was supposed to prevent conflict between bosses and employees (envisioned as ‘companions-collaborators’) and nip all desire for contestation in the bud. Members of the company were united by the same organic links as all members of the natural community. Free-to-obey workers and self-managing managers did not need to think about who they were and what they wanted, since they did not exist outside their common, biological drive towards growth.

Höhn’s approach was the only German alternative to the management theories of France’s Henri Fayol or the American Peter Drucker. His impenitent Social Darwinism found fertile ground in the 1950-70 world of the ‘economic miracle’, as notions of high growth, productivity and competition had previously driven the Nazis’ relentless quest for production and power. The ‘Bad Harzburg method’ was the pride of the FRG for decades. This method was supposed to be equally applied to the public sector and the anti-state, pro-agencies perspective of Höhn’s model appears as a precursor to New Public Management. However, after Höhn’s past caught up with him, Bad Harzburg fell into disgrace and new business models took over. Yet, Höhn continued to publish until 1995. When he died in 2000, he was saluted as a great thinker of contemporary management by the press from all sides and Chapoutot observes that he continues to have devoted followers such as Aldi, the mass distribution giant, quoting their managers’ handbook (Aldi, Manuel responsable secteur, s.l.n.d., rubric 4, unpaginated, quoted in Chapoutot, 125).

Chapoutot contributes to both the history of management and a broader well-established line of critical theorising on modernity. The Nazis’ managerial thought differed from other theories which emerged in the context of twentieth-century industrial capitalism. The Nazis’ focus on productivity can, of course, echo Frederick Taylor and Henry Ford’s ideas. The Nazis have been shown to have adopted Ford’s antisemitic critique of ‘productive’ (production-oriented) versus ‘parasitic’ (Jewish, lucre-oriented) economic endeavours, and their engineers modelled their Volkswagen plant on Ford’s River Rouge (Stefan Link, 2012). On a theoretical level, the Nazis’ mechanisation of the workers relied less on the glorification of machinery and technical competence than on organic metaphors supported by an imaginary folklore. Nazi workers were not artificially turned into productive forces: their productivity came from a biological imperative.

In this sense, the Nazi managerial thought shared similarities with Georges Doriot’s business philosophy, influenced by Alfred Whitehead’s vitalism (Martin Giraudeau, 2018). Höhn shared with Doriot a weariness regarding fixed theories and routinised procedures, as well as an understanding of business as a form of life. Yet they differed in their interpretation of what life was. For Doriot, life was the uncertainty at the core of business operations, a constant movement that could only be controlled thanks to a combination of ‘smell’ and careful examination and anticipation (Giraudeau, 2018). For Höhn, life was a movement ruled by the determinist laws of Social Darwinism: it just had to be lived, whether this was on the battlefield or in business. Höhn’s polar opposite was perhaps Drucker, for whom life was defined by its ‘meaning’ (or the absence of it) and who thought that work should enable the workers to realise themselves individually (Nils Gilman, 2006). For Drucker, ‘management by objectives’ did not mean that workers were free to obey, but that they should participate in the elaboration of objectives. Furthermore, Drucker did not conceive social promotion as an ideal that helped the workers keep quiet, but as a strategy to include and empower workers (Gilman, 2006).

By highlighting the striking parallels between the Nazi notion of Menschführung and modern managerial techniques, Chapoutot also contributes to the debate on the ‘modernity’ of Nazism, which has so far often focused on its anchoring in a particular historical moment, rather than on its influence on the present. The non-exceptionality of Nazism was first pointed out by the German ordoliberal movement. Rejecting the idea that Nazis were anti-state, the ordoliberals interpreted Nazism as an ‘invariant’ whose history could be traced back to the first critics of liberalism at the end of the nineteenth century, and whose elements of state socialism, economic planning and Keynesian interventionism appeared in other types of economy such as Soviet planning or the New Deal (Michel Foucault, 1979). The dismayed interrogation of what kind of ‘modernity’ could have produced Nazism, understood as an exception rather than an invariant, underlay Hannah Arendt’s reflections around the ‘banality of evil’ (Arendt, 1963), and generated various answers ranging from the Enlightenment obsession with rationality (Max Horkheimer & Theodor Adorno, 1947) to the influence of technology (Zygmunt Bauman, 1989). More recently, scholars have tended to depart from morally driven indictments of antisemitism to focus on the material forces that enabled the rise of Nazism at a transnational level, whether this was economic imbalances (Adam Tooze, 2006), support from various social classes with different motivations (Michael Mann, 2004) or a global rejection of liberalism steered by progressist fervour and belief in technology (Link, 2012).

Chapoutot in a sense combines and goes beyond these different schools of thought. He describes the Nazi approach to management as a product of both national history (the Prussian defeat against France) and transnational influences (German engineers ‘productivity missions’ in the US in the 1920s), and he links antisemitism, anti-state ideals and economic planning in situating them within a Social Darwinist matrix. Above all, Chapoutot dares to suggest how our current managerial thinking is in part a legacy of Nazism.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Nadia Matringe gives thanks to Rosemary Deller for her thorough editing and insightful suggestions, to Al Bhimani and Dmitrii Zhikharevich for their feedback on this review and to Dmitrii for having introduced her to a whole field of literature which she did not know.

Image Credit: Photograph of the Prora building complex on the island of Rügen, Germany, built as a beach resort designed for German workers as part of the ‘Strength Through Joy’ KdF project (Martijn van Exel CC BY SA 3.0).

This book has been heavily criticized in France. You can read a translated review here: http://www.letexier.org/?Johann-Chapoutot-s-reductio-ad-Hitlerum-When-ideology-prevails-over-historical