In Brewing Resistance: Indian Coffee House and the Emergency in Postcolonial India, Kristin Victoria Magistrelli Plys explores the Coffee House movement as a space of resistance or ‘autonomous zone’ that emerged to contest the authoritarian turn in India during the Emergency of 1975-77. This book is an important and timely reminder of the history of resistance that underscores the importance of tangible spaces in offering sites of protest against totalitarian regimes, writes Anand Badola.

Brewing Resistance: Indian Coffee House and the Emergency in Postcolonial India. Kristin Victoria Magistrelli Plys. Cambridge University Press. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

The world is witnessing a rising tide of totalitarian tendencies and democratic reversal. In a recent report by Freedom House, 2020 witnessed the largest increase in countries experiencing democratic decline. As a result of this, the world also witnessed a sea of protests resisting these totalitarian urges. From the George Floyd protests to the protests in Hong Kong to the ongoing farmer protests in India, there is growing resistance to oppression and state violence. It is in this context that Kristin Victoria Magistrelli Plys’s new book, Brewing Resistance: Indian Coffee House and the Emergency in Postcolonial India, offers a timely work of academic scholarship where diverse themes like economic development as politics, authoritarian rule and spaces of resistance converge.

The book revolves around the Coffee House movement as a space of resistance against the dictatorial turn that India took during the 1970s. But it also touches upon other themes which are relevant for our understanding of the nature of political praxis. The primary concern of the author is spaces of resistance in the face of totalitarian regimes. Such spaces are called ‘autonomous zones’, and Plys’s main argument is that the Indian Coffee House space was an autonomous zone during the Indian Emergency of 1975-77.

India’s Dictatorial Turn – Indira Gandhi’s Emergency, 1975-77

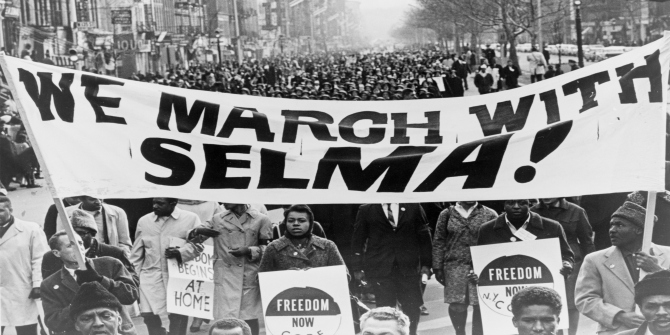

During the 1970s, then Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, faced a lot of criticism and protests against her government. Plys presents a detailed account of the social movements of the time as they protested the economic policies of the Indian government, including the Jayaprakash Narayan movement (also known as the Bihar movement, 1974-75), the Dalit Panther movement (1972-74) inspired by the Black Panther movement in the US, the Railway Workers’ strike (1974) and the Student Federation of India strike at Jawaharlal Nehru University (1975). These social movements were against Indira Gandhi’s economic policies which had broken the aura around the Indian government, such as issues of high corruption, allegations of nepotism and rising unemployment.

It was, however, the Allahabad High Court’s judgment in 1975, declaring Indira Gandhi’s electoral victory in the previous election as illegitimate, that prompted her to declare an internal emergency. In one swoop, India turned from a democracy to a totalitarian regime. Plys goes into detail describing the state repression during this time. Most of the political opposition was arrested and jailed, the press and media were suppressed and heavily censored and there were also programmes of forced sterilisation, engineered by Indira Gandhi’s son, Sanjay Gandhi. Even the judiciary caved in as it gave one of the most controversial judgments in Indian judicial history when it stated that even the right to life was not guaranteed during the Emergency. It is in the context of state repression that the Indian Coffee House at Connaught Place, New Delhi, emerged as a space of resistance, where dissidents from across ideologies came together to actively resist the Emergency. Plys calls this space ‘an autonomous zone’.

Spaces of Resistance – Autonomous Zones

But what is an autonomous zone? And how is it different from deliberative spaces of political discussion as envisioned by philosophers like Jürgen Habermas? The Habermasian notion of the public space, be this coffee houses, salons and so forth, is based on the premise that democratic institutions and culture are intact in a country. But what happens when there’s democratic decline or reversal and authoritarian regimes emerge? That is why Plys rightly prefers the concept of autonomous zones as the focus of the book is on totalitarian regimes.

Building on Saul Newman’s work, the author describes autonomous zones as:

a physical place where people gather to challenge dominant cultural and social norms and envision utopian futures. The radical politics of the autonomous zone are not just a disruption of the existing order of space […] The autonomous zone, in other words, is not just a social movement resource, nor is it simply a space in which to develop subversive discursive practices, but a space outside of state and capital in which artists and intellectuals can envision (and on a small scale, enact) alternate social practices and relations (46)

Hence, autonomous zones are unique spaces created by different actors across ideologies who have a common aim to imagine and fight for a world that is free of oppression. These spaces typically have intellectuals, artists and people from diverse political backgrounds engaging in vibrant discussions or making plans to subvert totalitarian regimes. The author’s main contention is that without such spaces, any kind of resistance to totalitarian regimes is not at all possible, as the state actively engages in form of repression that curtail the basic democratic practice of protest.

The Coffee House Movement

The second half of the book revolves around the story of the Coffee House movement in India and how the Indian Coffee House, having colonial origins, became an autonomous zone, especially during the Emergency. Plys traces the journey of the Coffee House movement during British Rule in India and how things changed after India gained Independence in 1947. The Coffee House workers formed a union in 1947 and were intent on forming a cooperative society from this. The author narrates the story of the Coffee House movement as a response to the Nehruvian policies of economic development during the initial decades of Indian independence. Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, driven by the modernisation theory of development, was determined to close the Coffee Houses, as he was against the idea of cooperatives.

But the Coffee House workers resisted, and Plys explores this aspect of the story in great detail. Indeed, this section almost feels like a different book as the focus turns to anti-colonial labour movements and their afterlives in decolonised countries. This is indeed the second line of enquiry pursued by the author, who explores what happens to these anti-colonial labour movements when ‘flag independence’ (merely political independence rather than the socio-economic liberation that the anti-colonial labour movement was pressing for) is attained. Drawing on the works of Frantz Fanon, Plys explores the transformation of the Coffee House movement as a continuation of the anti-colonial labour movement, a movement comprising workers controlling the Coffee House space.

An all-worker-run space, for Plys, is key for a space to be autonomous as the state and forces of capital cannot intervene in the inner functioning of such spaces. Hence, the author argues, because the Indian Coffee House was an autonomous zone, it was possible for it to become a space of resistance during the Indian Emergency. The author examines how this space was used by various dissidents to actively resist state repression. Building on interviews with people who were actively protesting during the Emergency, Plys tells the story of everyday resistance which the Coffee House made possible. It is here the book converges two ideas into one seamless and cogent story.

Futures of Resistance

Brewing Resistance makes a lasting impression as it discusses the importance of tangible spaces as places of resistance against totalitarian regimes. We can also see such autonomous zones emerging in the present day: for example, in the context of Anti-CAA protests in 2019-20 in India, where Shaheen Bagh emerged as an autonomous zone as people from diverse backgrounds came together, not only to resist the authoritarian tendencies of the state but also to envision a different path for Indian democracy. Similarly, in the current farmer protests, the farmers occupying areas around the border of New Delhi can be considered to form an autonomous zone. It is important that such spaces of resistance emerge, especially in an increasingly totalitarian world. It is vital that we do not forget to resist and protest at every turn of injustice; this book is a timely reminder of the history of resistance to give hope to the coming generations.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Image Credit: Photo by Antevasin Nguyen on Unsplash.