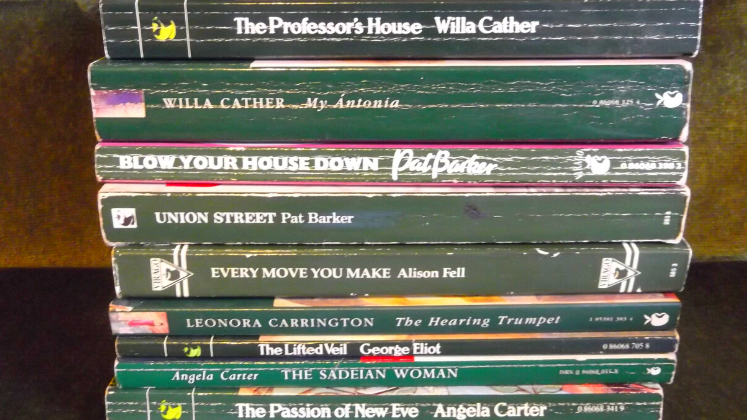

While the iconic green spines of Virago Modern Classics have become a fixture in the literary imagination, D-M Withers looks into the early history of feminist publisher Virago Press to explore how the decision to publish a fiction reprint list represented a significant change in the publishing strategy of a company whose main activity had been non-fiction, in new or reprint form.

Image provided by LSE RB editor

‘I thought, I’m going to start a fiction list, and I’m going to make the books look gorgeous so everybody will want to read them,’ recalled Carmen Callil (2010, 213). And with this impulsive thought – this publishing flight of fancy – the Virago Modern Classics were born.

It was a weekend binge-read of Antonia White’s Frost in May that made Callil arrive at such a thought. Michael Holroyd had lent her a copy. He had a hunch the story of a nine-year-old girl’s school days in an English convent would resonate with the Virago Press founder. This hunch proved to be true.

Frost in May was republished by Virago in June 1978, selling 11,401 copies by May 1980 – a bestseller for the company at the time [1]. It was the first title in a series that helped reshape literary history and popular reading habits in line with feminist forms. The Virago Modern Classics elevated the publishing value of the forgotten woman writer, and carved out enduring cultural recognition for the belated, lost and hidden.

The green spines of the series have since become a fixture of the literary imagination: blocks of dark colour that instated a quietly subversive and discernible feminist presence on shelves of bookshops, living rooms and bedside tables. A publishing idea so conceptually seductive and, in branding terms, aesthetically effective, it almost seems like their realisation was an inevitable chapter in Virago’s story of commercial success.

Yet when we look in detail at the early history of Virago Press, we can see how the Virago Modern Classics, as a fiction reprint list, did in fact represent a significant step-change in the company’s publishing strategy.

Virago Press, 1972-76: Research and Development

Virago Press were founded, initially as Spare Rib books, in 1972. Callil was joined in the venture by Rosie Boycott and fellow Australian Marsha Rowe, both of whom soon left to develop Spare Rib magazine. Virago Press were incorporated as a limited company in 1973, and operated as an editorial imprint of Quartet Books between 1973-76. Quartet were also a new publisher, established in 1972, with the aim of publishing books in the ‘Midway’ format, now commonly referred to as trade paperbacks.

At the time, trade paperbacks were the new and chic way of publishing. Unhampered by the cheapness and ephemerality associated with mass-market paperbacks, trade paperbacks were nonetheless affordable, unlike hardback books. For the small-to-medium-sized publisher, trade paperback publishing created new business opportunities. With lower print runs and break-even points, it created conditions for publishers to grow steadily and develop audiences for untested and ground-breaking books.

During Virago’s time with Quartet, the publisher was in a state of research and development. While Callil, who had been working in publishing since her arrival in Britain from Australia in the 1960s, had a wealth of experience – and contacts – to draw on, she had only worked in publicity roles. Along with Ursula Owen and Harriet Spicer who developed Virago in its early years, there was a need to upskill on the business side of publishing. Refining Virago’s publishing concept, and building an attractive and coherent list, was also vital.

The mission statement that adorns Virago’s first book catalogue clearly reveals the publisher’s intent. Virago were ‘the first mass-market publishers for 52% of the population — women’ [2].

The first list clearly speaks to readers with an interest in the politics of women’s liberation, and is notable for its heterogeneity. Fenwomen, by Mary Chamberlain, an account of village women’s everyday lives in the Cambridgeshire fens, was the first book Virago published. There is The British Woman’s Directory, a compendium of practical information about women’s liberation, for the well-informed and uninitiated. Mary Stott – Guardian Women’s Page editor and Virago advisory board member – features prominently with her memoir, Forgetting’s No Excuse, and edited collection Is This Your Life?, the first feminist media studies book published in Britain.

There are books about gender stereotypes, feminist spirituality, Russian women revolutionaries and sexuality. Angela Carter’s The Sadeian Woman is also listed. In October 1973, there were plans for Carter’s controversial cultural history to be Virago’s leading title, with manuscript delivery scheduled for Christmas 1974. Imagine the impact this would have made! Perhaps sending similar shockwaves to Germaine Greer’s The Female Eunuch, which Callil had managed publicity for in the early 70s? Virago eventually published Carter’s book in 1979 [3].

Virago’s first list was varied and interesting but there are two important things to note.

There are no reprints and no fiction.

During the first three years Virago were publishing, reprints were a minor consideration. There is even evidence that reprints were perceived within the company as a sub-category of the emerging Women’s Studies market [4].

Enter the reprint

So, what changed, and why?

The increasing importance of reprint publishing to Virago as the 70s wore on has a lot to do with the economics and business structure of Virago at the time. As already mentioned, Virago operated as an editorial imprint of Quartet Books between 1973-76. In practical terms, this meant Quartet had control over finance and business decisions. This was obviously not a satisfactory situation, not least for a feminist company, and Virago were keen to raise the money to become fully independent.

Building up a profitable backlist – and fast – was key to this process. This is not so easy to do with unknown authors. It also takes time to find and commission new work. Writers do not always deliver to deadline, life gets in the way (see Angela Carter, above).

With reprints, however, the book already exists. If a title has been languishing on a publisher’s backlist for decades – as many of the books Virago republished had – most likely it would be cheap to acquire publication rights. (This is arguably not the case today, with the boom in reprint publishing of all kinds.)

Image Credit: Cropped image of ’19th March 2017, green spines’ by themostinept licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Once rights were acquired, all that was needed was some clever work to reposition the title in the marketplace, revealing its relevance to the contemporary reader. For Virago and Callil especially, who was experienced and skilful in the art of publicity, this was the easy part.

Virago’s first publication as an independent company in January 1977 was, significantly, a reprint: Life as We Have Known It by Co-operative Working Women, originally published by the Hogarth Press in 1931.

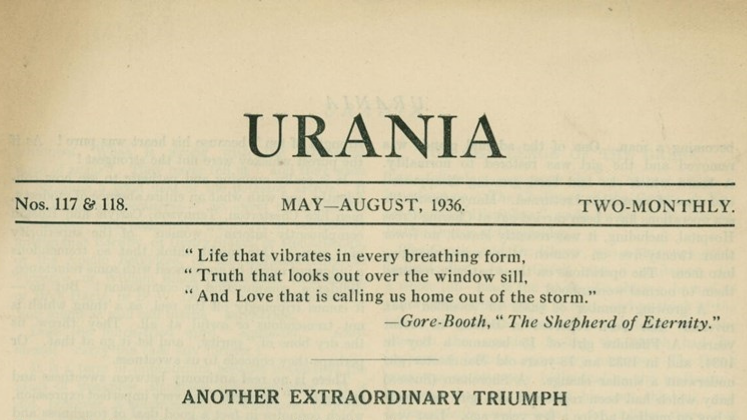

It was also the first publication in the Virago Reprint Library, ‘a series of out of print classics – history, memoirs, fiction’ [5]. The sequence of categories is worth dwelling on here. While not exactly an afterthought, fiction was certainly the poorer relation to history and memoir. This is further reinforced by the fact that the first six titles in the Virago Reprint Library were all non-fiction – histories and feminist social theory from the early twentieth century.

Despite intentions to publish one work of fiction in the Virago Reprint Library (Sarah Grand’s The Beth Book), this never materialised. Virago did publish this title, but as a Virago Modern Classic, in 1980. In total, eight books were published in the Virago Reprint Library before the series was edged out following the launch of the Virago Modern Classics, ‘a new series of outstanding out of print twentieth century novels.’ [6]

Knowing all this, if we return to the quote from Callil at the start of this blog post, we need to take its undertone of flippancy – of sudden change – seriously.

Surveying Virago’s first six years of publishing, we can see that the decision to start a fiction reprint list was a departure for a company whose main activity had been non-fiction, in new or reprint form.

This is not to say that the Virago Modern Classics did not represent the culmination of Virago’s publishing journey: throughout the 1970s, the strategy becomes ever focused, like a camera lens fixing on its object. But it was a departure nonetheless.

The enduring success of the series – it remains core to Virago’s publishing today – occludes our access to this earlier chapter in Virago’s history, a time when those famous green spines were barely a twinkle in Callil’s eyes.

Notes

[1] ‘Dear [blank] from Kate Griffin, 14 May 1980’, MS 5223, Box 11, University of Reading.

[2] ‘Virago: Our First Catalogue, Books for 1975-6’, Add MS 89178/6/2, The British Library.

[3] ‘Minutes from Virago meeting, 17 October 1973’, Add MS 89178/1/2, The British Library.

[4] ‘Factors We Consider When Taking on Books’, MS5223/10/11-1, University of Reading.

[5] ‘Virago: New Books and Complete List, June 1977-June 78’, Add MS 89178/6/3, The British Library. My italics.

[6] ‘Virago: New Books and Complete List, June 1978-June 79’, Add MS 89178/6/4, The British Library. My italics.

Note: This feature essay gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

The first book published by Virago was “Fenwomen”; not, as your article states, “Fenwoman”.

Thank you Jeremy, this has now been corrected.