In Uncivil City: Ecology, Equity, and the Commons in Delhi, Amita Baviskar explores the last two decades of environmental politics in Delhi, showing how the demands of ‘bourgeois environmentalism’ not only exclude the poor and marginalised from participating in environmental action but also positions them at the receiving end of violent modes of demolition and clearing. Published as we urgently examine urban inequalities in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, this book is critical to understanding the emergence of bourgeois environmentalism as a factor in the designing of New Delhi, writes Barathi Nakkeeran.

Uncivil City: Ecology, Equity, and the Commons in Delhi. Amita Baviskar. SAGE. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link): ![]()

In August 2020, the Supreme Court of India instructed the demolition of 48,000 jhuggi-jhopdis (hutments) that lined the railway tracks of New Delhi. Residents, activists and civil society organisations protested this order, particularly because it would effectively render over two lakh people (200,000) homeless in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic. Originally, this Supreme Court petition sought a solution to Delhi’s pollution crisis; it had nothing to do with housing and yet a case about pollution became about clearing poor people’s homes.

The courts’ disregard for the lives and bodies of the poor is part of a larger historical context involving the city’s urban planning processes and its environmental politics. Amita Baviskar’s Uncivil City – a collection of essays – explores this context by mapping the impact of bourgeois environmentalism on Delhi’s landscape and its social relationships. For instance, she notes that in 1996, as a result of a public interest litigation, the same court ordered hundreds of factories in Delhi to be relocated or shut down because they violated the pollution criteria in Delhi’s urban planning guidelines. Eventually, the factory owners chose to shut down instead of relocating, displacing several thousands of workers.

By ‘bourgeois environmentalism’, Baviskar alludes to a form of elite environmentalism that is governed by politics of aesthetics and a culture of modernity that is still haunted by colonial ideas of purity, public health and hygiene. Her use of bourgeois and upper class refer to instantly recognisable groups that are urban, elite, propertied, white-collar professionals: in sum, the owners of material and symbolic capital. Baviskar, an award-winning sociologist, has written several books exploring the cultural politics of environment and development in rural and urban India. In Uncivil City, her project is also partly an archival one. She probes the environmental politics of Delhi in the last two decades across various diverse spatial and social contexts such as residential spaces, workplaces, streets, extraordinary spectacles, a river and a ridge.

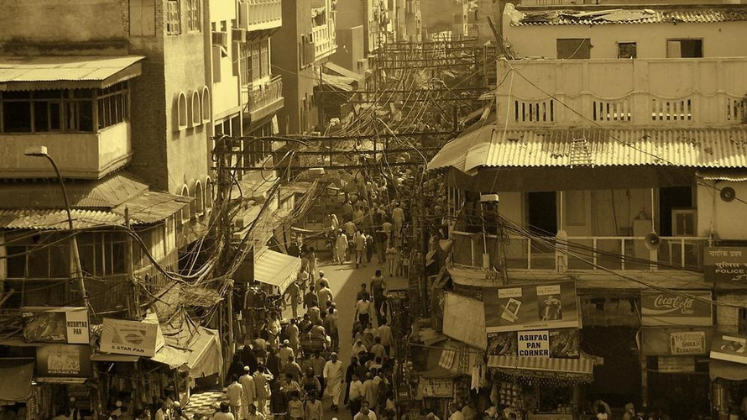

Image Credit: ‘Crowded streets of the Mina Bazaar’ by Soham Banerjee licensed under CC BY 2.0

At a simplistic level, a city’s residents and their desires determine the design of the city. However, the social relationships decide whose desires get to be heard and implemented. Urban planning, therefore, like other modes of ‘state making’, also holds the potential to exclude vulnerable and marginalised sections of the city from opportunities to both access the city and make it. The second chapter of Uncivil City provides a historical overview of Delhi’s urban planning. Baviskar illustrates how Delhi’s master plans – the city’s urban planning document – evidences an imagination of the city where certain pockets were preserved and nourished, and with it, its middle classes. At the same time, certain other parts were ‘cleaned up’ and their residents, constituting mostly working-class people and historically marginalised communities, were pushed out into ‘shanty towns’ and ‘informal settlements’, violating the city’s planned future.

However, much like other aspects of human life, desires and the complex ways in which they manifest are also difficult to discern. Therefore, while a ‘world-class’ city can, from its very outset, push marginalised sections of the city into greater precarity, it can still be something that ‘drums up consent’. Baviskar illustrates this with the example of the 2010 Commonwealth Games in Delhi. She describes the Games as a spectacle that manufactured consent despite the event displacing thousands of workers and causing severe exclusions, both monetary and otherwise. Aspirations like a ‘world-class city’, Baviskar argues, have the potential to persuade even those who might stand to lose that such a transformation is desirable.

Moreover, different groups of people can hold common desires, and yet have different pathways to pursue them. For instance, the desire for a ‘clean and green city’, Baviskar argues, much too often involves marginalised people, their bodies and their houses being equated with pollution. Cleaning up the city has involved pushing these lives to the margins. Such a process has been a common story in cities across time and space – New York, Beijing, Mumbai and Mexico City, to name a few, as David Harvey argues in his 2008 article ‘The Right to the City’. He argues that such an accumulation by dispossession is at the core of urbanisation under capitalism.

A variety of interlinked reasons inspire this iniquitous mode of city-making. One of the most important reasons for Delhi’s recent landscape of urban inequities is urged by bourgeois environmentalism, according to Baviskar; it adds epistemic violence to the already existing structural violence in urban planning, which renders and magnifies certain voices while silencing many others. This reproduces the unequal social relationships that govern the city of Delhi. Therefore, as Baviskar discusses in the fifth chapter, while cars are perceived as necessary and desirable despite their heavy contribution to air pollution, cycle-rickshaws, on the other hand, are sought to be banished.

What gets classified as an environmental issue, therefore, is dependent on these unequal power relations – who gets to be heard, as Gautam Bhan argues in his book In the Public’s Interest. The second reason, an interdependent one, is the judiciary’s role in catalysing bourgeois environmentalism: namely, how bourgeois environmentalists are able to frame concerns as matters of public interest while projecting this elite version of environmentalism as if it is universally urgent.

The poor and the marginalised are not only excluded from participating in environmental action; they are often at the receiving end of exclusionary and violent modes of demolition and cleaning. Concomitantly, environmental politics are also misjudged as elite conversations, denying visibility to the disproportionate impact of environmental crises on marginalised people, and also refusing certain concerns from being included in environmental discussions. For instance, Baviskar asks, are safer drinking water facilities for people in informal settlements an environmental concern? Tautologically, this results in a dichotomy where the concerns of the poor become labelled as specific issues as opposed to being considered as a component of a larger conversation around environment, social justice and public interest. Thus, a ‘clean and green city’ contains one too many contradictions. Environmental action in Delhi, Baviskar posits, is divorced of principles of ecological sustainability and social justice.

Though conceptualised before the pandemic, Uncivil City comes at a time when it has become crucial to examine urban inequities in light of COVID-19 and consequent state measures. When the government of India announced the national lockdown on 24 March 2020, the country began to crumble from within, and a large part of this was because those who build our cities – the working class – seem to be invisible in the eyes of the Indian state. This class of people, often occupying the most precarious of settings, are seen as encroachers and a threat to civic existence – something that needs to be cleaned up. In 2006, the human rights activist Usha Ramanathan, writing for the Economic and Political Weekly, argued that the constitutionality that ensured and protected the right of livelihood, housing and shelter had been supplanted by a legality that furthered the image of these citizens as encroachers. To this, Baviskar adds, not only does the judiciary play a role in arranging this exclusionary form of governance but it is also a significant component of it, wherein the judiciary is preferred by the middle classes to the ‘drawn-out struggle for administrative responsiveness and accountability’.

Bourgeois environmentalism and its hostility lies at the heart of the ‘Uncivil City’. The imagination of a world-class city does not hold within it space for messy, democratic dialogue of the streets. The new city that bourgeois environmentalists desire requires a violence that wrecks the city’s most marginalised, pushing them out to create space for the new urban order. Baviskar echoes what other Indian urbanists like Bhan argue: that rights in a city are not just in its physical space, but also includes having a say in political decisions regarding the use and allocation of urban resources including land and infrastructure. Although she does not quote this particular line of thought directly, Uncivil City seems to be in a conversation with Harvey’s sentiment that the kind of city we want cannot be divorced from the kind of social ties, relationship to nature, lifestyles, technologies and aesthetic values we desire.

Baviskar’s project, however, does not end with highlighting these polarising desires. She argues for a notion of ‘urban metabolism’, which – among other things– illustrates the unequal access and control of resources in a city. Such an analysis, she argues, would allow ecology to be made accountable to equity. Baviskar claims that she uses urban metabolism as a metaphor instead of a model, and this is perhaps one of the more confusing aspects of the book. Would metaphorising urban metabolism mean divorcing it of its quantitative mechanism as a tool to understand the consumption patterns of the city? Methodologically, therefore, it seems difficult to understand urban equity through this metaphor.

Uncivil City locates itself in the complex scholarship around Indian cities and marginality. We are at a moment – one that we have perhaps been approaching for a long while – where it is impossible to discuss any aspect of human life without considering the complex ways in which environmental politics impacts us. This book is therefore critical to understanding the emergence of bourgeois environmentalism as a factor in the designing of New Delhi.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.

Good articulated review