In Demanding Development: The Politics of Public Goods Provision in India’s Urban Slums, Adam Michael Auerbach explores why some urban slums in India are able to demand and secure public goods from the state while others fail. This interesting and well-written analysis will enhance understanding of how poor communities use democracy to ‘demand development’ in India and the mechanisms through which slum residents can increase their access to state resources, finds Mahvish Shami.

Demanding Development: The Politics of Public Goods Provision in India’s Urban Slums. Adam Michael Auerbach. Cambridge University Press. 2020.

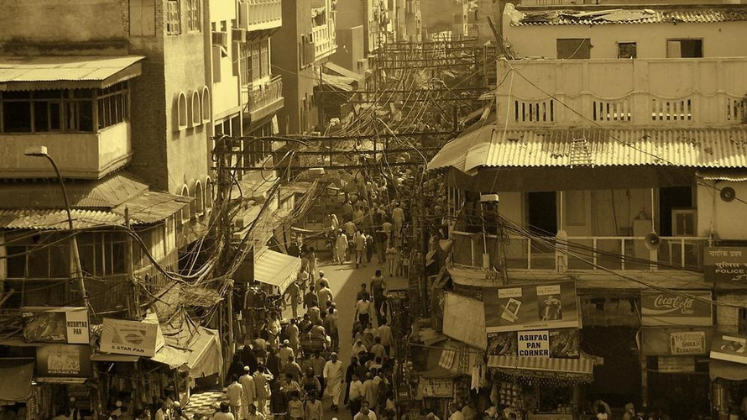

The last few decades have seen a shift in the landscape of poverty as populations have migrated from rural villages to urban cities in the hope of prosperity. However, since most of these immigrants were poor, they lacked the resources to afford proper housing in the city, and instead squatted in slums. These slums, along with having congested and semi- to non-permanent housing structures, also suffer from limited access to state resources. Yet slums are not completely deprived of state provision. Even a cursory look at these settlements will reveal that they do receive some public goods. However, this provision is fairly ad hoc, with some settlements enjoying considerable provision, while others have almost nothing.

The last few decades have seen a shift in the landscape of poverty as populations have migrated from rural villages to urban cities in the hope of prosperity. However, since most of these immigrants were poor, they lacked the resources to afford proper housing in the city, and instead squatted in slums. These slums, along with having congested and semi- to non-permanent housing structures, also suffer from limited access to state resources. Yet slums are not completely deprived of state provision. Even a cursory look at these settlements will reveal that they do receive some public goods. However, this provision is fairly ad hoc, with some settlements enjoying considerable provision, while others have almost nothing.

This begs the question of why there is variation in provision levels across slums. Despite slums being a hub of urban poverty, up until now this question has largely remained unanswered. Adam Auerbach sets out to answer this for India. His book, Demanding Development: The Politics of Public Goods Provision in India’s Urban Slums, explores why some slums are able to demand and secure public goods from the state while others fail.

The empirical analysis of the book is focused on Bhopal in Madhya Pradesh and Jaipur in Rajasthan. The choice of these cities might at first seem surprising: while they are large cities, they are not megacities like Delhi or Mumbai. However, as the author highlights, the majority of slum residents are found not in megacities, but in medium-sized cities spread across the country. Moreover, focusing on medium-sized cities has the added advantage of exploring how the poor cope when living in cities with lower state capacity and lower levels of visibility – the author quotes Mike Davis (2007) in calling these ‘faintly visible second-tier cities’ (36). Within these cities Auerbach conducted 2545 resident surveys in 111 slums. This dataset was complemented by rich qualitative data collected over fifteen months. This included ethnographic studies of eight settlements, along with interviews of politicians and government officials.

Image Credit: Cropped image of ‘Dharavi Slum’ by Jon Hurd licensed under CC BY 2.0

The combination of the qualitative and quantitative datasets allows Auerbach to provide extremely interesting insights into why slums enjoy varying levels of state provision. The variation, he argues, is explained by the ‘political organisation of settlements and the degree to which they are integrated into larger party networks’ (4). Settlements which have a dense network of party workers enjoy higher state provision, as party workers compete against each other for followers, and securing state resources shows their responsiveness to slum residents’ needs.

Moreover, the political party itself monitors the activities of these leaders/party workers, as inactivity on their part can be seen to tarnish the party brand. Dense party networks also have the advantage of offering residents multiple channels of political connectivity as slum leaders would now have access to political elites. Lastly, the network creates an organisational structure which can be relied on to rally slum residents. Combined, these factors enable slums with dense party networks to enjoy significantly higher provision levels, thereby improving their welfare considerably.

The question this raises is: what determines party density? Auerbach argues that this is impacted by two factors: settlement size and ethnic diversity. The first explanatory factor is fairly straightforward and intuitive. Large settlements attract the attention of political parties because of their size. Auerbach notes how slums are essentially seen by politicians as vote banks and therefore they are more likely to expend resources towards leaders in larger slums as they tend to have larger followings. On the flip side, he argues that large slums also incentivise the emergence of slum leaders within settlements – the large population size makes it more probable for them to secure decent-sized followings in the settlement. This multiplicity of leaders means there is a greater number of people that can be brought into the party organisation, which in turn results in greater levels of provision for the reasons mentioned above.

The second explanatory variable is ethnic diversity. According to Auerbach, ethnically diverse slums produce denser party organisations and therefore enjoy greater state provision. This at first seems counter-intuitive as the literature mostly finds that ethnic diversity can be detrimental to public goods provision. However, Auerbach argues that ethnically diverse slums tend to have a greater number of slum leaders – at least one for each ethnic group. Over time these leaders are brought into the party fold and therefore become part of the party organisation. Thus, ethnic diversity allows for the establishment of dense political networks. What Auerbach also notes is that in most Indian slums, a leader’s non-ethnic characteristics, such as charm and connectivity, are of greater importance to residents than their ethnic background. As a result, ‘while higher levels of ethnic heterogeneity tend to increase the density of party workers, ethnicity does not rigidly define linkages between residents and party workers’ (207).

According to UN-Habitat, 850 million people live in slums, and the figure is expected to rise in the future (3). These are poor residents of the city, living in precarious settlements, who, unlike regular citizens, are unable to rely on programmatic provision. Yet our understanding of how they survive in the city is still fairly limited. Auerbach’s book makes a substantial contribution towards improving this. Using detailed qualitative data combined with an extensive quantitative dataset, he convincingly explains why certain slums are better than others at gaining access to state provision. Moreover, he gives insights into how slums function, both in terms of how leaders are picked – ranging from discussions amongst residents, to informal elections, to their gradual emergence over time by demonstrating their ability to get things done – and the agency residents enjoy.

Furthermore, the book adds a new dimension to explaining vulnerability: the extent of political organisation. Based on the results presented here, one would argue that when determining which slums are most vulnerable and thus most in need of government attention, levels of political organisation must be taken into consideration. Slums which lack political organisation are least likely to be able to mobilise resources from the state and therefore should be allocated more resources. Lastly, the book makes us rethink the negative relationship between ethnic diversity and public goods provision. As Auerbach himself notes, ‘the mechanisms operating between ethnic diversity and public goods provision are of course complex, numerous, and likely uneven in the direction and magnitude of their effect’ (232). Still, the findings of this book demand that scholars explore the relationship in more detail and with an open mind.

Overall, the book is an interesting analysis of how the poorest of the poor use democracy to ‘demand development’ in India while living in a settlement which tends to be ignored in developing countries. It is extremely well-written and it contains interesting qualitative interviews that not only help explain the mechanism behind the results, but also bring the slums to life for the reader. I thoroughly enjoyed reading Demanding Development and feel it has greatly enhanced my understanding of how slums function and the mechanisms through which these residents can increase their access to state resources.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.