In Displacement: Global Conversations on Refuge, editors Silvia Pasquetti and Romola Sanyal bring together contributors to explore different experiences of forced migration at local, regional and global levels. Advancing conversations around how localised humanitarian responses interact with the larger global context, this is a timely, profound and thought-provoking collection, writes Husne Akgol.

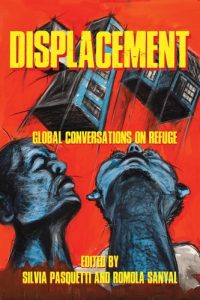

Displacement: Global Conversations on Refuge. Silvia Pasquetti and Romola Sanyal (eds). Manchester University Press. 2021.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

‘When the Polish Police caught us, they beat us, and destroyed our mobile phones. They broke my friend’s hand and let their dogs loose on us. It was really scary!’ reports an Iraqi asylum-seeker stranded at the Belarus-Poland border in search of access to the European Union. The ‘migrant and refugee crisis’, as coined by the United Nations, at the Belarus-EU border is currently one of the most ardent debates around refugee crisis displacement, yet one that is purported to be a crisis manufactured for political ends by the Belarusian leader.

This, however, is far from the only case in which refugees are manipulated for political purposes and used as bargaining chips, as in Turkey’s decision to open its borders with Greece and Bulgaria in 2020. With the significant rise of right-wing populism, persons fleeing persecution are refused access to safety under the pretext of preserving state security, whereas human security tends to be neglected. At a time when forced displacement has reached a historic record of over 82 million people globally, and policies of externalisation, deterrence and exclusion are practised at varying scales across a significant majority of states, Displacement: Global Conversations on Refuge is extremely timely and pertinent.

Displacement is co-edited by two prolific academics, Dr Silvia Pasquetti, a political sociologist and urban ethnographer working in law, urban studies and refugee studies, and Dr Romola Sanyal, Associate Professor in Urban Geography, whose research mostly focuses on urbanism and forced migration. The book thus reflects the interdisciplinarity and intersectionality that both co-editors aspire to achieve and have long employed in their work.

Displacement aims to transcend a mere account of forced displacement situations or developments across the globe. Rather, it engages in extensive conceptual exploration of the complexity embedded within the comparative nature of forced migration. To this end, it emphasises the need to adopt a relational approach which allows for interactions among different scales of forced migration at the local, regional and global levels. As such, it attempts to advance conversations around how localised humanitarian responses interact with the larger global context.

Image Credit: ‘View of the sprawling Kutupalong refugee camp near Cox’s Bazar, Bangladesh’ by Russell Watkins/Department for International Development licensed under CC BY 2.0

A rather interesting example of this is presented in Tazreena Sajjad’s chapter on the Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh, which illustrates how global norms and policies are diffused to and adopted at the local level. Sajjad shows how the securitisation of refuge, which is predominantly practised by the Global North, is exercised within the localised humanitarian responses of the government of Bangladesh against the Rohingya refugees displaced from Myanmar.

In addition to its cross-regional approach, Displacement also aims to advance interdisciplinary conversations by going beyond the disciplinary siloes in which the field of forced migration is trapped (2). It achieves this by incorporating urban studies, history, geography, race studies, political science and biopolitics into the field of forced migration and by utilising various qualitative methodologies including ethnography, historical archives and textual analyses of official discourses.

The chapter by Chia Youyee Vang, for example, is a good example of how history could be utilised in making sense of state responses to forced migration situations. Vang links the emergence of US humanitarianism policy and the ‘rescue and liberation myth’ (33) toward Hmong refugees to its history of imperialism and militarism in Vietnam as per its anti-communist foreign policy. Vang uses historical archives of the Hmong refugees resettled in the US following the US decision to disengage from Southeast Asia during the Cold War. This chapter speaks greatly to the book’s effort to ‘decolonise’ refugee studies from its American/Eurocentric standpoint, mainly by tracing the historical trajectories of imperialism, racism and power through the lenses of refugees. Similarly, the rich background of contributing writers also challenges the convention of discussing the realities of displacement in the Global North, whilst the significant majority of situations take place in the Global South.

I found Konstantina Isidoros’s chapter on Sahrawi nomads in North Africa particularly noteworthy not only in terms of its depiction of how the global (humanitarian systems) interacts with the local (the Sahrawi nomads), but also in terms of the starkly disparate meanings attributed to ‘refugee’ status by the Sahrawi versus by humanitarians. As a nomad community roaming the Algerian desert, the Sahrawi are equipped with the knowledge, skills and capacities necessary to navigate the desert ecology. However, as they expect their nascent nation state to be recognised, they inadvertently became refugees after the Moroccan invasion of West Sahara. ‘To the Sahrawi, they are citizens of their nation-state-in-waiting receiving the humanitarians as visitors’ (156).

The political agency of refugees, a recurrent theme throughout the book, thus takes a completely different form here, where the Sahrawi are the main agents and decision-makers within their ‘glocality’, whereas the humanitarian workers are visitors who share refuge and need protection. Isidoros employs the Foucauldian term ‘heterotopia’ to describe the Sahrawi camps as ‘juxtapositions of incompatibilities in a single space’ (155). The camps are nothing unusual for the Sahrawi, but are more so for the humanitarians, which is contradictory to the conventional presumption of refugees as in need of protection and shelter. Thus, the chapter presents an antithetical form of relation between humanitarians, as representatives of the global, and the Sahrawi locals.

In expanding the theoretical avenues of forced displacement studies within the realm of biopolitics, Jonathan Darling’s chapter on distance, deferral and immunity in the urban governance of refugees deserves special attention. Darling presents the spatial and discursive distancing of refugees by the UK through practices of outsourcing, externalising and offshoring migration management. He employs Roberto Esposito’s conceptual framework of biopolitics, where the communitas, or a community of individuals tied to each other by common obligations, strives to preserve its immunity, namely its identity and constitutive order, from external threats by distancing them.

This spatial distancing is practised by states either in the form of externalisation and offshoring of refugee reception facilities or in the form of ‘selective incorporation’ of refugees to fulfil international commitments. Selective incorporation of threats in immunology is necessary for the body’s production of antigens, during which the body incorporates and neutralises these threats, which helps to keep the immune system functioning. This neutralisation, Darling argues, is managed in the UK through refugees’ dispersal across marginal, de-industrialised locations, which works to keep them insulated from the rest of the constituents of the communitas, and hence public discourse.

Displacement advances our understanding of forced migration by accentuating the transnational, historical and interdisciplinary lenses through which the field could be conceptualised and theoretically enriched. Through profound and thought-provoking chapters, it goes beyond its promise of circumventing disciplinary siloes to arouse readers’ curiosity about other potential areas of inquiry that could be problematised in relation to forced migration. Thus, Displacement will appeal not only to scholars, students and practitioners within the field of forced migration, but also to those working across a number of other disciplines and areas of study.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.