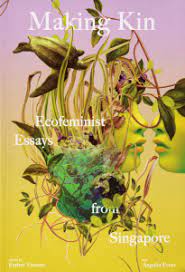

In Making Kin: Ecofeminist Essays from Singapore, editors Esther Vincent and Angelia Poon offer an evocative collection of personal essays by a diverse group of women as they experience life in Singapore and beyond. Eloquently crafted to ‘make time’ for ruminating on the overlapping discourses of selfhood, family, home, community, nation and ecology, this book will be of interest to readers of ecofeminist and ecocritical literatures, writes Alexandria Z.W. Chong.

Making Kin: Ecofeminist Essays from Singapore. Esther Vincent and Angelia Poon (eds). Ethos Books. 2021.

It has been nearly five decades since Françoise D’Eaubonne coined the term ‘ecofeminism’ in her 1974 book Le Feminisme ou la mort (Feminism or Death). Generations of academics and activists have sought to (re)examine and augment the ways in which feminist and ecological matters of concern intersect by deconstructing historical binaries such as man/woman, culture/nature, reason/emotion and theory/practice within Western thought (Douglas A. Vakoch and Sam Mickey 2018). Therefore, at its core, ecofeminism is about making visible the connection between the structural oppression of women and the destruction of the environment under a capitalist, patriarchal global order.

It has been nearly five decades since Françoise D’Eaubonne coined the term ‘ecofeminism’ in her 1974 book Le Feminisme ou la mort (Feminism or Death). Generations of academics and activists have sought to (re)examine and augment the ways in which feminist and ecological matters of concern intersect by deconstructing historical binaries such as man/woman, culture/nature, reason/emotion and theory/practice within Western thought (Douglas A. Vakoch and Sam Mickey 2018). Therefore, at its core, ecofeminism is about making visible the connection between the structural oppression of women and the destruction of the environment under a capitalist, patriarchal global order.

The eighteen personal essays in Making Kin form an exploratory dialogue that interrogates the experiential ways in which gender (and, to a far lesser extent, sex and sexuality) connects with nature, life and embodiment. It opens with Esther Vincent’s ‘The Field’, which traces her childhood memories. Through the language of poetry, she weaves together a constellation of intellectual thoughts (primarily Martin Heidegger’s topology of being, place and world) with Singapore’s perpetual territorial transformation. This lyrical essay zooms in on the displacement of human and non-human species, bringing the reader on a fleeting journey of loss and longing.

In ‘The Spell of the Forest’, Prasanthi Ram confronts her hylophobia (the fear of wooded areas). The dark, balmy spell of the tropical jungle morphs into the paralysing fear of contracting COVID-19 as Ram, a PhD candidate, is her father’s caregiver. The parent-child relationship is also explored by several other essayists. In ‘There Will Be Salvation Yet’, Tania de Rozario reflects on her troubled relationship with her mother and how religion magnifies within a person what already exists. And in ‘Coming Home: Healing from Intergenerational Trauma’, Nurul Fadiah Johari writes about how the intersecting forms of injustices of gender, class and race affect the mental health as well as the wellbeing of women in her family. For Johari, reconnection or the act of ‘returning home’ begins with communal meals and other everyday rituals learnt from her Nenek (grandmother) and Ibu (mother).

Dawn-joy Leong’s ‘Scheherazade’s Sea: Five Women and One’ excoriates the social-political-cultural-economic structures of shame and subjugation as well as the brutal plundering of Earth in the name of ‘development’. As an autistic person, Leong assiduously recounts her formative years of being forcefully trained to see and experience the world ‘from the prescribed, normative human-centric paradigm’ (110). This opposes the sensing-cognitive quality of the autistic mind, which Leong describes as being attached to a network of sentience within the living environment.

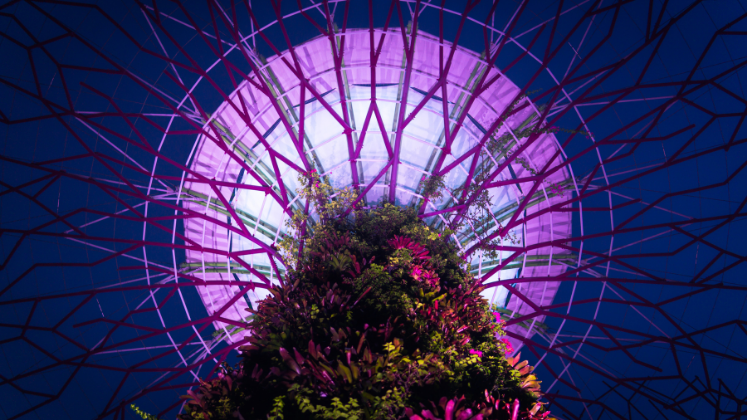

Image Credit: Photo by Kit Suman on Unsplash

In ‘Marvels of Nature Just Outside My Window’, veteran civil activist Constance Singam takes a tender introspection into the troublesome periods of illness and depression. Singam’s essay complements fellow climate and disability activist Tim Min Jie’s ‘Care is Revolutionary’. Written during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic, Tim expresses her desire to ‘feel more anger’ (187) towards the draconian laws that put migrants (employed in Singapore’s construction, manufacturing, service and marine shipyard sectors) under the longest period of COVID-19 confinement faced by anyone in the world. Tim then confides to the reader her raw struggles with burnout while drawing on the ethics of care as an active prefiguring of a better world to work towards. The volume closes with Diana Rahim’s ‘Liquid Emerald’, which traces the lasting colonial denigration of native and traditional forms of medicine and, by extension, knowledge.

With its autobiographical subject matter, the eclectic and expansive collection of personal essays in Making Kin creates a deep sense of intimacy between the essayist and the reader that soars above theoretical abstractions. The conversational tone and occasional inventiveness in structure help tease out the quotidian truths experienced by the essayist while inviting the reader to mediate within an ecocentric praxis of kinships and entanglements. These personal essays get as detailed and, perhaps, as uncomfortable as the essayist chooses to interpret the women-nature connection.

Although the back cover asserts that the volume ‘blurs the boundaries between the personal and the political’, few essays actually manage to achieve that. The volume does not construct a dialogue across differences (which the capitalist patriarchy interprets as hierarchical) to explore the tensions between ‘global’ and ‘local’, two concepts widely circulated within ecological and development discourses. This omission is analytically glaring as Cynthia Enloe (2014, 343), paraphrasing the second-wave feminist slogan, reminds us that ‘the personal is international, and the international is personal’ when it comes to questioning the logics of capitalist patriarchy.

Owing to the editorial choice of centring personal essays as a textual medium, Making Kin is also at times too liberal with its interpretation of what women-nature connections count as ecofeminist in their orientation, value, practice and/or principle. This is exemplified by Andrea Yew’s ‘Grappling’ (on being a judo practitioner), Poon’s ‘Travelling in Place’ (on the sojourner as a literary figure) as well as Grace Chia’s ‘Conquering Yeast’ (on the comfort and joys of breadmaking during lockdown). Readers looking for discussions that further ecofeminism as a relational praxis will have to engage with literature elsewhere.

Editor Vincent’s personal note to the volume, where she recalls her own experiences of reading Eating Chilli Crab in the Anthropocene that ‘inspired [her] to edit a book of similar imperative’ (12), underscores the complexities of foregrounding women’s voices while tapping on the democratising potential of personal essays to frame Singapore’s postcolonial development. There is a missed opportunity to engage with topical Singaporean subjects, such as urban agriculture and food security (the ’30 by 30’ vision was introduced in 2020) as well as family planning (pro-natalist policies were introduced in 1987, reversing one-and-a-half decades of anti-natalist policies). It would also have been analytically worthwhile for essays in the volume to draw on postcolonial ecofeminist literature from South and Southeast Asia.

Nonetheless, the genial collection of essays in Making Kin is, in the context of contemporary Singapore literature, ground-breaking to say the very least. They engage with personal events unfolding in the past, present and future (sometimes all at once), filling the reader with a vicissitude of emotions and thoughts on the overlapping discourses of selfhood, family, home, community, nation and ecology. However, for those looking for critical perspectives from and about Singapore, the volume’s attempt at viewing the world through an ecofeminist lens intermittently lacks the urgency to ‘critique, influence and change’ (Maria Mies and Vandana Shiva 2014, xiii). Perhaps greater editorial reflexivity and criticality on what ‘nature’ means within the women-nature connections that essays in this volume have sought to make visible would have been beneficial. Put simply, Making Kin is an ingenious piece of work that could ‘make more time’ to contemplate the inter- and intraspecies kinships and entanglements in Singapore and beyond.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.