In Hegemonic Mimicry: Korean Popular Culture of the Twenty-First Century, Kyung Hyun Kim explores the global rise of Korean popular culture, using the concept of ‘hegemonic mimicry’ to examine how it has adapted American sensibilities and genres. This is a valuable and significant contribution to studies of Korean popular culture with an interdisciplinary approach that will appeal to scholars across different academic disciplines, writes Beyza Dogan.

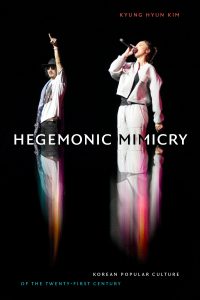

Hegemonic Mimicry: Korean Popular Culture of the Twenty-First Century. Kyung Hyun Kim. Duke University Press. 2021.

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

Hegemonic Mimicry discusses the rise of Korean popular culture, ‘hallyu’, in global settings. As author Kyung Hyun Kim aptly presents, popular culture in South Korea is formed through two identities – hegemonic American culture and local culture. Amid the strain between the two, the mimicry and adaptation of American culture have enabled the creation and success of hallyu (29). Depicting a clash of two cultures, Kim scrutinises Korean popular culture by drawing on several examples and theoretical concepts, including from K-Pop, K-Cinema and Korean television, although K-dramas and K-games are not included in the spectrum.

Hegemonic Mimicry discusses the rise of Korean popular culture, ‘hallyu’, in global settings. As author Kyung Hyun Kim aptly presents, popular culture in South Korea is formed through two identities – hegemonic American culture and local culture. Amid the strain between the two, the mimicry and adaptation of American culture have enabled the creation and success of hallyu (29). Depicting a clash of two cultures, Kim scrutinises Korean popular culture by drawing on several examples and theoretical concepts, including from K-Pop, K-Cinema and Korean television, although K-dramas and K-games are not included in the spectrum.

With the recent global popularity of Korean cultural products and the growing number of fans around the world – such as the K-Pop group BTS and its followers, ‘the Army’ – academic studies of Korean popular culture have increased in number. Some of the existing literature published on Korean popular culture has examined various dynamics in the sector, such as fandom and government subsidisation, drawing on real-life cases and examples (see, for instance, The Korean Wave edited by Yosue Kuwahara). Kim has approached this growing topic through previous academic books and articles, focusing particularly on Korean cinema, where he is also active professionally as a producer and scriptwriter.

The common theoretical approaches used in academic studies of Korean popular culture are cultural diplomacy, soft power and transnational cultural flow. In Hegemonic Mimicry, although Kim mentions such theories, he mainly explains his argument through the concept of mimicry, which South Korea also uses in other sectors to innovate, as outlined in Chapter Six, ‘Korean Meme-icry: Samsung and K-Pop’.

The book consists of seven chapters and a lengthy introduction. The chapters are interrelated but not sequential. In the preface, the author introduces the concept of ‘mimicking the west’ by explaining how Korea dealt with COVID-19 by creating its own pandemic control system after it redeployed Western medical technology (X).

The book opens with an imagined reversal of the history of the American army in Korea. Here, Kim describes a hypothetical dystopian world in which America is in the place of Korea, war ravaged and struggling economically. Then, a transoceanic army of Koreans comes, and their culture and identity surpasses anything American (2). This scenario creates a hook for the reader, much like in a fiction book, and enables readers to empathise with the position of Koreans.

For those who have recently developed an interest in Korean popular culture, the introduction gives a comprehensive overview with plenty of background information. Kim argues that, dating back to the presence of the US army in Korea, Korean identity has been situated between white and black identities, defined by Kim as an ‘off-white/blackish’ positioning. Korean identity finds itself defined by twoness – by hegemonic American culture and local culture (29) However, the author argues throughout the book that Koreans are redefining ‘becoming minjok’ (Korean national ethnic identity) through popular culture that mimics American culture but also competes with it globally.

Image Credit: ‘KARA 4th ALBUM SHOWCASE’ by m-louis .® licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Korean popular culture is based on the Korean language and does not take its power from the diaspora or cultural proximity based on the consumption of media from or close to one’s own culture (19). It has become hegemonic, but it is mimicry by nature. Hence, hegemonic mimicry differs from other cultural theories that explain the spread of one country’s culture, such as flows from the Global South or media imperialism. This conceptual framework provides readers with a method to analyse popular culture and mimicry in nations positioned between two identities.

In Chapter One, Kim broadly elaborates on the history of Korean popular culture. He starts with the example of K-Pop, emphasising that it has formed through the impact of African-American hip hop and J-Pop from Japan. The spread of K-Pop is explained with the examples of the singer PSY, who opened the door to America for K-Pop, and the group BTS, who grew with the fan force called ‘the Army’. Kim points out that K-Pop is seen as key to the export of other goods. Kim also briefly gives information about the ‘slave contracts’ that K-Pop idols have with their management companies. Kim could expand upon this discussion of the conditions for creatives in Korea and the struggles they face during trainee processes and afterwards, though he does present some details in Chapter Six.

Kim then describes K-Cinema as ‘Asia’s Hollywood’, with films mainly revolving around the topics of North Korea, period dramas and gender war comedies. It is interesting to read that K-Cinema admissions are growing and it is regaining its audience through local productions. Kim here also briefly states the relationship between K-Cinema and China and the possibility of the absorption of the former by the latter. The topic of K-Television is discussed by introducing over-the-top (‘OTT’), online video streaming platforms, like Netflix and Hulu, and their negative impact on TV viewing. In this part, Kim focuses on reality shows instead of K-Dramas.

In later chapters, Kim elaborates on K-Pop, K-Cinema and K-Television through an analysis of specific examples. Chapter Two argues that Korean rap positions itself differently than K-pop and takes its essence from both p’ansori – a Korean critical storytelling tradition – and African-American rap/hip-hop culture. Although Korea does not have the physical space of ‘the ghetto’ to inspire rap music, the education system and other social problems have influenced the development of Korean hip-hop culture.

Chapters Three and Five examine topics surrounding K-Cinema, such as body switch films affected by digital age surveillance and the significance of food and eating in recent movies. Extreme Job (2019) and Parasite (2019) are analysed in detail in Chapter Five to suggest that K-Cinema is starting to reflect real-life problems, such as class divisions and social inequality, through laughter and food. In both chapters, the author uses different concepts drawn from the works of W.E.B. Du Bois, Gilles Deleuze and Frantz Fanon. In spite of this, the descriptive aspects of the chapters outweigh the theoretical parts, as the author does not explain the concepts in detail. Thus, as a reader, I found it difficult to relate the concepts to the examples.

In Chapter Four, focusing on K-Television, Kim elaborates on ‘The Running Man’, a TV variety show, through his term ‘affect Confucianism’. This refers to a value system that incentivises hierarchy in social structures, but differs from capitalism by promoting collective identity instead of dividing people into winners and losers (143). Although Kim also draws on the idea of ‘transmedia storytelling’ – the dispersal of a story across multiple media tools – to explain the global success of ‘The Running Man’, the explanation of how it contributes to this remains weak. Later, in Chapter Seven, ‘Muhan Dojeon’, another Korean TV hit, is analysed in terms of its similarities with madangguk – a satirical theatre that emerged during the minjung movement, a 1970s pro-democracy project that criticised the government for leaving the public out of economic, political and cultural fields.

As mentioned earlier, Chapter Six approaches mimicry from another perspective by focusing on Samsung. The author emphasises the similarities between K-Pop and Samsung in their approaches to innovation, production and working conditions while becoming hegemonic. It is argued that the working conditions of Samsung factory workers who became seriously ill are similar to those of K-Pop idols who have experienced mental health problems and have even taken their own lives in some cases. This topic needs to be debated further to explore what the success of K-Pop takes from a generation.

Although hegemonic mimicry is introduced as the overarching theoretical framework for this book, the chapters adopt different concepts that are sometimes not directly related to mimicry. Further explanation of the quotes and concepts used in these chapters would help the reader make connections between the analysis and the examples.

Nevertheless, Hegemonic Mimicry is a valuable and significant contribution to the literature on Korean popular culture studies by introducing the concept of ‘hegemonic mimicry’ in detail and approaching Korean popular culture in an interdisciplinary way. This feature of the book will attract scholars from various academic disciplines as well as university students from different backgrounds.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.