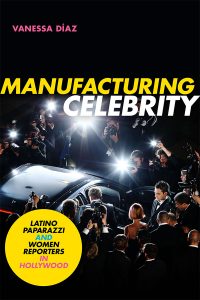

In Manufacturing Celebrity: Latino Paparazzi and Women Reporters in Hollywood, Vanessa Díaz demystifies the role of the Latino paparazzi and women reporters in celebrity media production. At a time of great upheaval in labour markets, Díaz’s interdisciplinary analyses at the intersection of work, race, gender and media are particularly insightful and relevant, writes Jonathan Pye and Sara Castro Cantú.

Manufacturing Celebrity: Latino Paparazzi and Women Reporters in Hollywood. Vanessa Díaz. Duke University Press. 2020.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

In Manufacturing Celebrity, Vanessa Díaz critically examines and demystifies the role and position of the Latino paparazzi and women reporters in celebrity media production. Manufacturing Celebrity is a participant-ethnography written over a period of approximately ten years whilst Díaz was working at People magazine. It offers a study of precarious labour and how the ‘Hollywood-industrial complex’ depends on, and weaponises, these workers. The two populations under study – the paparazzi and celebrity reporters – experience this precarity in different ways. At a time of great upheaval in labour markets, Díaz’s interdisciplinary analyses at the intersection of labour, race, gender and media are particularly insightful and relevant.

A guiding analytic through Manufacturing Celebrity is that of visibility and invisibility and how the politics of vision intersects with those of inclusion, racialisation and sexualisation. Throughout the ethnography, Díaz highlights how celebrity visibility is manufactured through the invisibility of the Latino paparazzi and how paparazzi inclusion depends on this invisibility. Likewise, the politics of vision impacts the work of female reporters. Unlike the Latino paparazzi, they are visible on the red carpet; however, this visibility results in their sexualisation and the reinforcement of heteronormative understandings of female sexuality. As a result, for both women reporters and the Latino paparazzi, visibility comes with risks – it is an opportunity for the surveillatory politics of celebrity media production to cement their relative precarities.

Surveillance therefore emerges as a distinguishing theme throughout the ethnography. The Latino paparazzi intimately surveil the celebrities; however, the surveillatory politics and logics within Hollywood serve to racialise and exclude the paparazzi from full participation within celebrity media production. Similarly, female reporters surveil celebrities on the red carpet; however, this surveillance is once again reversed, and they become the highly sexualised object of Hollywood’s gaze.

Photo by Clem Onojeghuo on Unsplash

Manufacturing Celebrity opens with an exploration of the Latino paparazzi in Los Angeles. Díaz focuses mostly on one paparazzo, Galo, and his experiences driving around Hollywood and trying to take the most sought-after photographs. Her analysis emphasises how the Latino paparazzi are denied equal access to celebrity media production: instead of attending red carpet events, they shoot from the sidelines, withstanding harassment and spending hours each day hiding and waiting inside their cars. This denial of access is predicated on the racialisation of the paparazzi who are portrayed as aggressive, illegal and ‘other’. They are easily disposable and interchangeable and are frequently racially and linguistically profiled.

As Díaz explores in Chapter Three, this racialisation of the paparazzi comes with risks. The racialising logics that marginalise the Latino paparazzi also resulted in the concomitant erasure of the death of a Latino paparazzo, Chris, who died following an interaction with the police. Díaz explains that the work of the Latino paparazzi is intimately associated with the ‘economics of violence’ (97): these ‘economics’, in tandem with racialisation, rendered Chris disposable within the Hollywood-industrial complex. After his death, online discourse focused on assigning blame to him, with little to no consideration of his life or humanity.

This perceived disposability also results in efforts to legislate against the paparazzi and perform hatred toward them in order to signify status and to gain empathy within celebrity media. Díaz labels these ‘media rituals of hate’ (119) and explains that they function as an extension of ‘social death’, or denial of personhood. The Latino paparazzi, in many ways, occupy a state of ‘social death’ resulting in the amplification of celebrities’ and consumers’ hatred for the paparazzi. This sharply contrasts with the movement and socioeconomic value of the media they produce. The legitimacy of the Latino paparazzi as a cultural producer is thus denied.

Much like the Latino paparazzi, women reporters experience precarity in similar yet contrasting ways. Unlike the paparazzi, whose work often takes place close to celebrities’ homes and workplaces, female reporters are more likely to be found on the red carpet and at legitimised spaces and events. Díaz offers a fascinating analysis of the red carpet in Chapter Four, explaining that it is intimately related to the cultural concept of celebrity and elitedom. The iconicity of the red carpet has become a ‘media ritual’ (127) and is used within Hollywood to naturalise and legitimate order and distinction. Furthermore, these same reporters are also sexualised by heterosexual, male celebrities and through their visibility on the red carpet, thereby reinforcing heteronormative attitudes towards women’s sexuality and the female body.

These heteronormative attitudes towards the female body are especially prevalent in coverage on celebrity weight loss and weight gain. Such coverage reproduces toxic understandings of the ‘ideal’ female body. Díaz’s analysis is especially insightful here, as she explores how such coverage depends on imaginary or ‘parasocial’ (219) relationships between consumers and celebrities and the psychocultural importance of these relationships in the construction of celebrity media culture.

Díaz’s writing style throughout Manufacturing Celebrity is clear, powerful and compelling. Both thorough and accessible, Díaz is successful in grabbing the attention of both students and scholars of media as well as of the casual reader. Díaz’s approach is interdisciplinary, borrowing from anthropology, sociology, media studies and cultural economics to bring to life the unexplored and understudied lives of the paparazzi and celebrity reporters, and to paint a rich tapestry of the processes that result in the invisibility of these racialised and gendered labourers.

Her methods, which include one-to-one conversations, interviews, ethnographic observations and personal insights from her own work on celebrity magazines, inform her analysis of the Hollywood-industrial complex and of the people that help create it. By interviewing and writing about specific paparazzi, reporters and interns, Díaz accomplishes the task of giving a voice and a face to those who are often rendered voiceless and invisible. Her insights and conclusions have wide-reaching implications for the politics of labour, media and economics: for example, in her discussion of how Donald Trump simultaneously used celebrity media practices to build his brand, while also humiliating and belittling reporters and the media throughout his presidency.

Manufacturing Celebrity is a book for students of ethnicity, culture and contemporary media as well as for those interested in the socio-political discourses regarding celebrity culture in the US. Díaz writes a comprehensive and detailed account of the lives of those who are sidelined in the process of manufacturing celebrity and integrates theory without sacrificing the human perspective. As Díaz herself writes, ‘the book provides a better understanding of the reporters’ and paparazzi’s work, lives and struggles, as well as how their lives and struggles impact the media they produce’ (250). Its target audience is therefore those interested in gaining an in-depth understanding of the intersections between class, race, gender and labour.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.