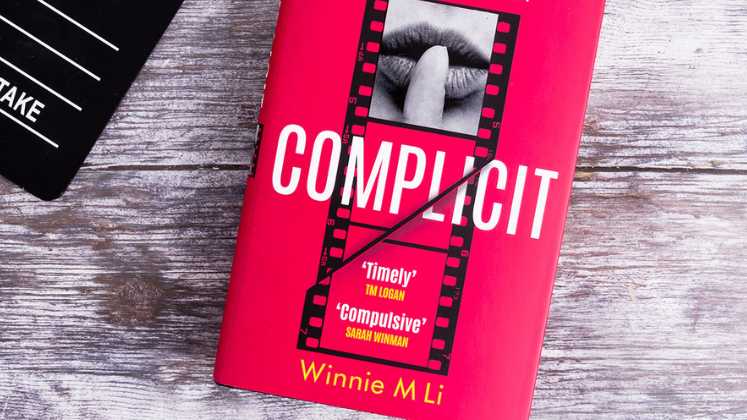

‘Like the best filmmakers, Li draws you to the edge of your seat and keeps you there’. Following Winnie M Li’s debut novel Dark Chapter, winner of the Not the Booker Prize 2017, Complicit is her new thriller that follows protagonist Sarah Lai as she reflects on her past experiences of silence, suppression and abuse in the film industry. We speak to Winnie M Li about writing the novel, delving into workplace practices and webs of complicity, the power of fiction for social justice movements and the need for spaces of collective healing.

Q&A with Winnie M Li on Complicit. Orion Books (UK)/Atria Books (US). 2022.

Q: Could you introduce Complicit to readers?

Q: Could you introduce Complicit to readers?

Complicit is a mystery set in the world of filmmaking. 39-year-old Sarah Lai teaches screenwriting at a local college, but was once an aspiring film producer. When she’s approached by a New York Times journalist about a powerful male producer she once worked with, she’s forced to confront the truth of her ruined career in the film industry — and how she may have been complicit in certain injustices. It’s obviously inspired by the #MeToo movement, but also by my own experiences in film — and as a sexual violence survivor, who has done a lot of thinking and consulting on how we tell these kinds of stories in the media.

Q: How invaluable was your past experience as a film producer when writing Complicit? When did you decide that the film industry would be the setting for your second novel?

Oh, I wouldn’t have been able to write the book if I hadn’t previously worked in film. So much of it thematically is rooted in a lived experience of that industry and understanding how it ticks. I worked for a London-based production company for six years. I’ve been to Cannes, I’ve been to the Oscars, I cast A-list actors before they became famous. I wanted to capture all the manufactured glamour of that world, while also showing the hard work, graft and inequality of it. From the moment I first had the idea for Complicit, I knew it was always going to be set in the film industry. (From a practical perspective, it’s also because I knew I wouldn’t have to do a huge amount of research either!)

Q: Complicit shows how abusive practices can be tolerated and ignored – and the consequences of this. Yet you also show how workplace structures can make it difficult for individuals to challenge such behaviour. How important was it to explore these complex layers of complicity in the novel?

In some ways, that was the whole reason I wrote the book! Shortly after the Harvey Weinstein allegations broke, a friend remarked: ‘I don’t get it. If people knew Weinstein had been doing this to women for years, how was he able to get away with it for so long?’ And I remember thinking ‘Ah clearly, you’ve never worked in the film industry before…’ So what I wanted to do in Complicit was show how and why professionals in these workspaces would turn a blind eye to that kind of behaviour – because they don’t want to endanger their job, because they’re ambitious about their own careers, because they don’t feel like they would even be listened to or taken seriously. And how that, compounded over years, results in irreparable damage done to lives and to careers. A lot of it’s about the loss of talent from workplaces and industries – all the films by women which never got made, because they were bullied or ignored or worse.

Q: Complicit shows how those in the creative industries, especially women, can be diminished by everyday work dynamics – whether unacknowledged labour, precarious contracts or being treated as dispensable ‘fodder’. Do we need to address this economic vulnerability if we are to properly challenge abusive behaviour in all its forms?

Yes, absolutely. The economic vulnerability – the precarity – is what enables the abusive behaviour, because predators know they can get away with bullying, deception and worse in an environment where workers are so worried about losing their job or their gig. You can’t expect to stamp out abusive behaviour without setting up systems of accountability, where the behaviour can be reported, where there can be consequences for the perpetrators – and more importantly, where young workers can feel there are the structures in place to support them, so they can reach their greatest potential within that industry.

Q: Thinking about other recent high-profile works addressing #MeToo in the film and television industries, such as The Assistant and Bombshell, were there any tropes that you sought to avoid or challenge when writing Complicit?

I thought The Assistant was brilliant, and Bombshell was entertaining and well done, too. They were both great portrayals, again, of that precarity which young women are often subject to in the media industries. I think I was most conscious of these being a very white portrayal of the #MeToo issue – you didn’t find many characters of colour (if any) in these stories, and the female protagonists were, of course, white and conventionally attractive. Once you introduce race and class into the narrative, the precarity – and the potential for abuse and for injustice – are even more emphasised. So through Sarah’s character, I wanted to show how being a child of immigrants, being Asian-American and financially challenged in a predominantly white, affluent industry, means you have to work even harder to get your foot in the door and to be taken seriously. And that the potential for being exploited or overlooked is even greater.

Q: Complicit builds the story and tension by interweaving Sarah’s first-person narration with interview transcripts with a number of female colleagues, including her boss Sylvia. What led you to fold these different voices into the novel?

It was actually in a fairly late draft that I decided to fold in those different voices. From a writerly perspective, I think I felt that Sarah’s voice was a little too dominant and I needed something to break up her monolithic narration. And thematically, it was important to show the various perspectives that other players might have had on these issues. There are multiple sides to any story, of course. Not only it is the journalist’s job to investigate these multiple sides, but it’s also our job as readers – and as humans – to consider how other people, of a different age, class, social status, etc, might react to something that happens. Some of the other women interviewed in Complicit are not sympathetic to victims, some are quite blind to what’s happening, while some are even more vulnerable than Sarah.

Q: Something that comes over powerfully is Sarah’s wariness about engaging with a journalist, yet she seems to find a growing agency and self-understanding in telling her story. How does this speak to your own PhD research into how rape survivors enter into and experience different forms of media engagement?

I think in general, rape survivors are wary of engaging with the media, because there is a fear their story and their words will be distorted and exploited. There is good reason for this. Many of the survivors I interviewed for my PhD research felt that on some level their very personal story of trauma was being used by media outlets for ‘content’. There wasn’t much care put into how that material was obtained (impersonal, unsympathetic interviews, for example) or how it was presented (unflattering photos of the victims, sensationalist word choice, etc). There are so many media practices that can impact a victim’s personal, emotional experience of telling their story. And yet, nearly all victims tell their story because they want the truth and the injustice to be known. So I wanted to capture that tension in Complicit: can Sarah trust the journalist with her story? Will that go some way towards repairing the injustice that was committed years ago?

Q: Your PhD research explores how social, economic and cultural capital can affect which survivor voices are heard in the public sphere. How did you thread this theme into Complicit?

It undergirds the entire book. Because the issue of capital – which enables certain survivor voices to be heard in the public sphere – is the very same determinant of who gets to work in the creative and media industries in the first place. So of course it tends to be photogenic, media-savvy, middle-class survivors whose voices are heard or whose stories are told. When it came to #MeToo, you had A-list Hollywood actors, household names but also very skilled media professionals sharing their story – and that celebrity aspect is what blew up the news cycle. In Complicit, Sarah is very aware that she is an unknown name to the public, that no one’s really going to care about her story – but just maybe, compiled alongside much bigger names, her story can now make a difference.

Q: Your research is partly rooted in interviews with rape survivors and partly in an auto-ethnography of your own experiences of being a public rape survivor, author and activist. Did writing Complicit shape the way you approach these methodologies in your research?

While my PhD research definitely fed into writing Complicit, I can’t say it was the other way around: that writing Complicit directly affected my PhD research. Practically speaking, I found it quite difficult to balance two large projects that take up your headspace in very different ways. Plus writing fiction is a very different approach from the methodologies I’m using for my PhD! But who knows? I’m heading into writing up my data collection now, and perhaps something Complicit-influenced will come up… That’s the beauty of writing. You never know, until you write it!

Q: What role can fiction play in the work of academics and other changemakers who are seeking to address social justice issues and engender social transformation?

I think fiction and creative storytelling can play a huge role. You reach people through empathy: by identifying with a fictional character, readers gain a better emotional understanding of how individual lives are affected by an issue, and why change needs to happen. A lot of academic and ‘change-making’ work can be quite dry: statistics, data-oriented research, policy discussions, intellectual debates. You have to inject the humanity for an issue to really hit home. That’s why the best social science research doesn’t lose sight of the fact that these are human experiences, individual lives that we are studying.

Q: At the beginning of Complicit, Sarah seems quite isolated following her past experiences in the film industry. Given your own role in setting up the Clear Lines community, how important is it to create such spaces of collective healing, sharing and action?

It’s very important to have a community, especially when you’re dealing with issues of trauma or injustice. One of the things that can compound the trauma is that sense of isolation, that you’re entirely on your own dealing with the impact of abuse. I founded Clear Lines partly because I was feeling so isolated when I was writing my debut novel Dark Chapter. In the process, I realised there are so many fellow survivors, artists, activists out there who want to bring about change surrounding sexual violence, so I wanted to create a collective space for us all to be in dialogue with each other. That’s also what the #MeToo movement did for victims: enabled a collective space for our stories and experiences to be heard, and for us to find a commonality and a community. And I think that’s what fiction can enable as well!

Further reading/listening

Official Complicit book launch with Marai Larasi, Professor Liz Kelly, Rowena Chiu, Dr Katherine Angel and Professor Joanna Bourke – hosted by The SHaME Research Hub at Birkbeck College, University of London. Watch the panel discussion here: https://shame.bbk.ac.uk/blog/complicit-silence-vs-speaking-up-in-hollywood-and-everyday-workplaces/

New York Times review of Complicit

Winnie M Li interview with Times Radio on ‘Sexual Abuse in the Film Industry’

Interview with Winnie M Li on PBS show, ‘Story in the Public Square’

Note: This interview gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The interview was conducted by Dr Rosemary Deller, Managing Editor of the LSE Review of Books blog.