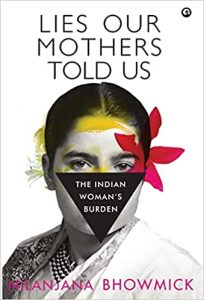

In Lies Our Mothers Told Us, Nilanjana Bhowmick explores the structural constraints that impede empowerment and gender equality for middle-class women in India. Weaving together personal stories and journalistic investigation, the book presents these middle-class women’s experiences and negotiations in an accessible manner, write Riddhi Bhandari and Sriti Ganguly.

Lies Our Mothers Told Us: The Indian Woman’s Burden. Nilanjana Bhowmick. Aleph Book Company. 2022.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

‘She wanted to make sure that she was seen not only as a professional woman earning a salary but also a good homemaker’ (1), writes Nilanjana Bhowmick about her mother in Lies Our Mothers Told Us. Working mothers have to strike a bargain and manage both paid work and domestic responsibilities. The guilt at not doing or being enough perpetually haunts working mothers in addition to the fatigue of being constantly overworked. Lies Our Mothers Told Us tells the story of women who dare to aspire and find themselves juggling work and home. They are constantly shown their ‘rightful place’ at home, in workplaces, in informal gatherings and in public spaces. Myriad forms of violence embedded in social structures continue to shape the everyday lives of these women.

Bhowmick weaves stories of growing up in a patriarchal household, witnessing her mother’s struggles and negotiations, with her journalistic investigations into the lives of similar women from different parts of India. The discussion moves from case studies to macro-level reflections on policies and structural constraints that impede empowerment and gender equality.

A few themes stand out. First, the absence of institutional support that hinders women’s progress at every step. Chapter Two critically evaluates the well-intentioned Right to Education (RTE) Act of 2009 that mandates equal schooling opportunities for children. It is disturbing to read that when Bhowmick visited villages in Uttar Pradesh in 2018 and 2019, she found young girls immersed in household chores while their young brothers scrolled away on mobile phones. Girls looked exhausted and disinterested in the classroom. In rural India, the disproportionate burden of household and farm chores continues to be a leading cause of irregular schooling among girls and their higher dropout rates after primary level. An Act that is celebrated for making elementary education free and compulsory still fails girls. While it enshrines education as a right, minimal effort is made to address societal patterns or provide institutional support that will enable girls to stay in school.

Image Credit: Photo by Nikhita S on Unsplash

The lack of sanitary toilets is another major impediment that keeps girls away from schools and women away from the streets. Similarly, the absence of childcare centres for working mothers hinders their labour force participation. There is also a failure of imagination on the part of governments and policymakers when it comes to understanding and prioritising women’s needs. This becomes evident when a crucial item, like the sanitary napkin, never makes the government’s list of essential items. Unsurprisingly, it is one of the first items to be cut by families under financial strain, as happened when the COVID-19 lockdown was announced.

Similarly, Bhowmick discusses the gendered nature of public spaces where women are conspicuous by their absence. Like Shilpa Phadke (2007) and others, Bhowmick emphasises women’s right to loiter and claim public space without fear. However, modern Indian cities continue to be unsafe for women, where they face myriad forms of harassment. In the name of safety, women either take themselves off the streets or engage in the exhausting mental labour of calculating risks and strategies to navigate public space ‘safely’. Technocratic solutions to this unequal access and skewed gendered presence in public spaces centre on increased surveillance as a remedy. Smart city projects belabour the need for safety apps and more CCTV instead of broader social shifts to make cities more gender-inclusive spaces. These required changes range from ensuring access to clean public toilets, better socialised men and a gender-sensitised and responsive police.

The double burden of managing home and wage work is another theme in the book. The pandemic revealed this as working from home for women meant managing gruelling routines of unpaid domestic and care work, attending to children’s education and to their own wage work. Bhowmick alludes to time-use surveys that have repeatedly shown that women dedicate disproportionate hours to household work in comparison to men; in rural or poor urban areas, women spend a large amount of time queuing up for and ferrying water (Chapter Nineteen).

This double burden of work, Bhowmick argues, has only been compounded by a narrow conception of empowerment that has perpetuated the ‘lie’ of the ‘multitasker goddess’, according to which women are expected to juggle different forms of work successfully and without complaint.

Chapters Ten to Twelve situate such ‘empowerment’ in the intersections of capitalism and patriarchy to consider its implications for women and work. Bhowmick weaves together employment data and the quotidian life stories of women who are engaged in different forms of paid and unpaid work. These personal accounts offer insights into how women’s entanglements with work are simultaneously unavoidable, burdensome and precarious. On the one hand, domestic and care work continue to be the exclusive and unpaid domain of women. On the other hand, because of the demands of domestic and care work, women’s participation in wage work remains uncertain, undervalued and underpaid. They are often the first casualty in downsizing efforts as became evident in the sharp decline in women’s employment during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Image Credit: Photo by Tushar Arora on Unsplash

Bhowmick points out that even in contemporary capitalism, women continue to be valued much more for their reproductive than their productive labour. Workplaces are not designed with women and their needs in mind, whether for childcare or for flexible working hours and spaces. Women are also seen as unreliable, distracted, less efficient and more likely to discontinue work after marriage and/or children. Women internalise low self-worth, are more likely to settle for low-paying jobs and have difficulty articulating demands for better wages or flexible working conditions. The double burden of work also pushes many women out of the workforce: too ashamed to explain the demands of domestic work, such exits reinforce the perception of women as unreliable, short-term employees. The alternative is to find jobs that fit the template of the ‘multitasker goddess’. The desirability of teaching is one such example discussed in the book as it allows women to strike a ‘balance’ between unpaid household work and paid employment.

Yet, Bhowmick also emphasises that in capitalist economies, women are increasingly seen as consumers. There is a slew of products and ads targeted at them: electronic appliances to simplify domestic chores, packaged foods to simplify cooking as well as jewellery and other luxury consumer goods for traditional festivities. One could add beauty products and services to the list. However, the implications for women’s freedom and empowerment are mixed at best: while these products simplify certain aspects of life, they still delegate the sole responsibility for domestic and care work to women and they assign value to women only when they fit the familial and societal schema of being ‘good’.

Bhowmick also critically evaluates the celebrated trends of ‘leaning in’ and the related figure of the ‘superwoman’ (or the ‘girl boss’ for Gen Z). This refreshing discussion analyses the continued lack of support for women even in workplaces headed by women. Informed by patriarchal classifications that associate productive labour with men, work culture and workplaces require that women act like men to succeed. Hence, women who cannot ‘lean in’, who need flexible working hours and are unable to draw a strict separation between work and home, are seen as weak and do not typically receive the support they need. We see this in the contemporary debates over menstrual period leave (90). Some of the strongest pushback has come from successful working women who worry that this demand centres a woman’s sex/gender, thus reinforcing the idea that women are weaker, different and less employable. In workplaces, ‘empowerment’ mantras don’t alter the unequal gendered structure of workplaces; they only lend weight to the idea that women do not belong in the workplace unless they can act with male privilege.

This is where Bhowmick unpacks the ‘lie’ referred to in the book’s title. This is the promise of change – a more equal and better world for empowered, employed and urbane middle-class women. The fact that the modern woman in a democratic nation can have it all is a lie and the women in Bhowmick’s book see through this: they do not see their lives as ‘having it all, but rather as having to do it all’ (27).

The costs of this lie are manifold and reveal the limits of choice. Women are overwhelmed, exhausted and often make peace with everyday misogyny and harassment to continue working. Bhowmick documents the perpetual state of anxiety, unhappiness, guilt, self-doubt and overall poor mental health that can even push women to consider suicide: another excruciating price women pay to maintain the lie. She provides data to show that women ideate about and attempt suicide far more frequently than their male counterparts (Chapters Four and Seventeen).

Furthermore, women’s experiences with modern clinical therapy reveal its limitations in addressing women’s trauma. Aside from being expensive and exclusionary, many women in Bhowmick’s book expressed their disappointment with therapists who often failed to understand that women’s issues are rooted in their gendered positions in a patriarchal society. Women frequently turned to spiritual gurus, alternative forms of healing and collective ritual participations such as in satsangs (a gathering of followers for religious sermons) to cope with the demands of their lives. Here, women found empathy and reported feeling more comfortable articulating complaints, unhappiness and disappointments.

Such unexpected communities of shared experience also coalesce around women vloggers, who document the private and everyday goings-on in households (Chapter Thirteen). This chapter was reminiscent of Sara Ahmed’s (2021) explorations of the importance of complaint as feminist pedagogy that has the potential to foster critical consciousness, solidarity and new kinds of collectives, even as ‘due process’ frequently fails the complainant.

Now a few points to quibble. An aspect that seemed central but was left relatively unexplained was the author’s understanding of ‘the middle class’. There is academic literature on the fuzziness – even deceptiveness – of defining the middle class (Deshpande 2006; Dickey 2016). Perhaps ‘middle class’ is deliberately left unexplained in the book because it is an affective location that transcends financial/material means. In any case, one wishes Bhowmick had been more explicit about her definition of the middle-class Indian women that inform her book. Additionally, the book barely approaches the category of women through an intersectional lens that acknowledges caste and religious overlaps and differences.

Image Credit: Photo by Belle Maluf on Unsplash

More importantly, why are the lives of middle-class (mostly urbane) women in India a particularly important segment for this study of persisting gender disparities and patriarchal norms? In Chapter Two, Bhowmick discusses the lives of adolescent girls from rural upper-middle-class families who own agricultural farms. ‘Being middle class in rural India means girls must face added pressures that affect their education, like having to fetch water […] or perform agricultural or household labour’ (15). In what ways is the situation different in poor rural households?

Perhaps the book is situated in Sara Dickey’s focus on the pervasiveness of middle-class values and aims to highlight that, despite change, there is a staidness regarding women’s social position. An important point is how middle-class women hesitate to talk openly about abusive and violent relationships or even openly criticise their partners and fathers. This has been tied to the idea of middle-class respectability that silences, conceals and controls narratives of family life and relationships. While the absence of support structures is a strong factor that keeps women in abusive relationships, upholding respectability is an equally important element. The women that this book focuses on allude to the aspirations of the middle class – education and employment as key vehicles of change – to show how these have not panned out as expected when it comes to women’s lives and social positions.

One also wishes that the book had delved into women’s workforce participation as bringing value beyond wages. Particularly important to us as a sociologist and an anthropologist is the opportunity women have through their work to expand their social networks beyond the friends and associates they share in common with their husbands. These are available to women through worship groups, micro-finance groups, the much-maligned kitty party groups and through vlogging communities. They can empower women to imagine a world beyond the one they currently inhabit and to have a support system that is their own and distinct from their familial one. Exploring the potential of work as a site for such networks is an important thread for future research.

Bhowmick also points out that empowerment remains at the level of financial or digital empowerment and women still lack intellectual empowerment. But what intellectual empowerment entails, and how it can be achieved, are unexplored themes. This is particularly jarring because of Bhowmick’s contention that ‘for most middle-class women the term feminism is either scary or something that has no direct bearing on their lives’ (91). The book’s exclusion of suggested ways towards ‘intellectual empowerment’ given the alleged failure of ‘feminism’ is striking because there seems to be no way out of the lies and burdensome lives for Indian women. The book mentions a few silent forms of resistance – showing up in the kitchen with a book that would rile the matriarch or not making an effort to cook a delicious meal, fearing that it would tie them to the kitchen forever. But these instances are scarce.

Lies Our Mothers Told Us is not shocking, especially to those who mindfully live around and as working women in modern India. But what the book does, effectively and affectively, is deeply sadden. What disappoints is the striking similarity of patterns and worlds across space and time. In this way, the book provides several ‘a-ha’ moments. Bhowmick writes that often women wanted someone to say to them, ‘I hear you’. Just as spiritual gurus, vlogger communities and satsang groups ‘heard’ women, Lies Our Mothers Told Us does the same by connecting readers with Bhowmick and the women whose experiences and complaints she documents. While the claim that the lives of middle-class women have not gained attention is not entirely correct, Lies Our Mothers Told Us presents their experiences and negotiations in a more accessible manner.

Note: This review gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science. The LSE RB blog may receive a small commission if you choose to make a purchase through the above Amazon affiliate link. This is entirely independent of the coverage of the book on LSE Review of Books.