In Nehru’s India, Taylor C Sherman reevaluates the role of Jawaharlal Nehru, India’s first Prime Minister, in shaping the nation, identifying and interrogating seven myths that have elevated and isolated Nehru as the lone protagonist of India’s independence story. This book offers a promising reimagination of India during its formative years under Nehru, writes Poorvi Gaur.

Nehru’s India: A History in Seven Myths. Taylor C Sherman. Princeton University Press. 2022.

Architect of independent India, non-alignment, secularism, socialism, a strong state, successful democracy and high modernism – these seven terms are used generously when engaging in dialogue around India’s first Prime Minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. How did early independent India become synonymous with Nehru’s approach not only in public discourses and electoral politics but also in academic texts? Taylor C Sherman’s Nehru’s India provides riveting answers. Sherman contextualises the seven abstract nouns that informed the first two decades of independent India’s socio-political history, positioning them as myths. For the author, a myth is not the whole story. These over-simplified representations of the era, Sherman argues, elevate but also isolate Nehru as the lone protagonist of India’s independence story.

Adopting an archivist’s gaze into the past, Nehru’s India critically scrutinises each myth across seven chapters. In doing so, Sherman’s account of early postcolonial India brings forth an insightful revisionist history that traces the making of myth and separates the ‘shadows of truth’ from it. She points the reader to crucial but missed dimensions of the ‘Nehruvian era’ to see past and present discourses in a new light.

The book begins with a rich description of a Films Division of India documentary titled Nehru (1984). Made 20 years after his death, the film presents a larger-than-life portrait of Nehru amidst scant contributing voices. Sherman utilises Nehru’s narrative to establish the trend of how scholars, bureaucrats and civil society perceived Nehru’s sole and dominant status in shaping India’s early life. Sherman’s arguments arrive at a time when Narendra Modi-led right-wing leaders systematically attack Nehru for the issues of early and present-day India.

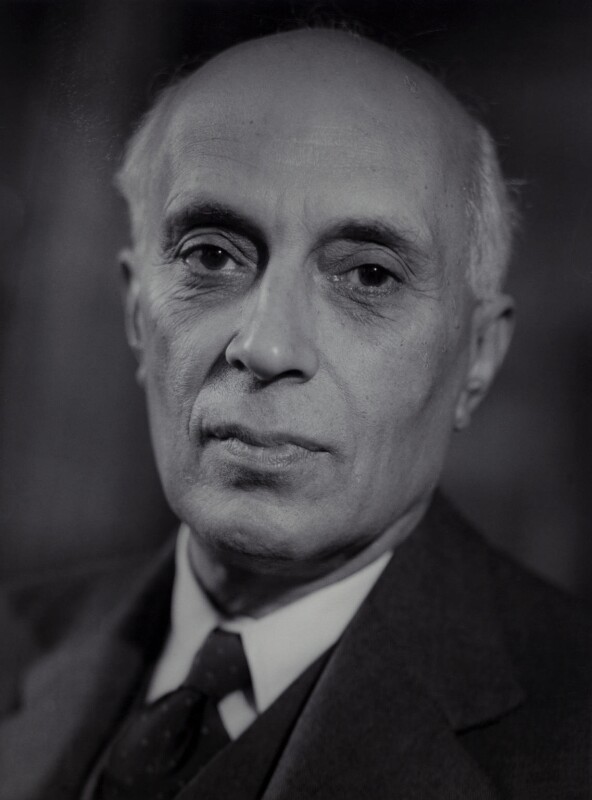

Image Credit: ‘Jawaharlal Nehru’ by Howard Coster, print, NPG x2067. Licensed by the National Portrait Gallery under CC BY NC ND 3.0

In the first chapter, Sherman dismantles the notion of Nehru as the ‘architect of India’, questioning the historical usage of this term. Unsubscribing from the legend of ‘The Great Man’, she finds an exhausted Prime Minister who preferred the presence of critics who he hoped would continually ‘pull [his government] down a peg or two’ (6). Was Nehru keen on forming a personality cult, even a soft one? The answer, Sherman argues, is a firm ‘no’. In cementing such a myth, history writers inevitably leave out incidents that otherwise pollute the clear stance of their argument. Sherman pulls out one such event in 1958 when Nehru proposed to retire but was forced to continue at the behest of his party. It is this small forgotten incident that raises crucial questions about Nehru’s ‘legacy’.

Sherman also examines India’s foreign policy under Nehru and urges the reader to think of this history in ‘imperfect, unstable and overlapping lines’ (33). Sherman argues that deconstructing India’s vision of the international order as a singular ideology resting in nonalignment overlooks the dynamic interplay of approaches India undertook to tackle its relationships – good, bad and ugly – with other nations. An interesting metaphor used to describe the extent of India’s policy on nonalignment during the Cold War is the comparison of the latter to a six-yard saree. India’s stand on nonalignment constituted only the intricate patterns of Zari embroidery on its borders and pallu ends: it ‘drew the eye, but the rest of the garment was woven with a different thread’ (51).

In the third chapter, Sherman deconstructs the myth of secularism. She presents a rich set of arguments that distinguish between the two forms of secularism in postcolonial India. One was an idealist dream, part of Nehru’s visions for India. The other was a facade comprising of tokenistic gestures focused on ‘monumental spaces, revered personalities and iconic pieces of legislation’, which left ordinary Muslims and Dalits ‘beleaguered and frustrated in their daily lives’ (82). The former was an aspiration; the latter, a messy reality. While Sherman observes a small group of senior leaders who sought to assure marginalised communities of their peaceful integration and acceptance within Indian society, bureaucratic practices continued to vilify and discriminate against them. That Nehru’s secularism extended to the inclusion of all minorities, including Dalits, foregrounds an important aspect of the revisionist framework, especially when contemporary debates on Nehru’s project of secularism are played off as a project that was directed at Muslim appeasement. Similarly, the chapter on the myth of India’s democracy questions its assumed successful implementation, the caste-based reservation system being a case in point.

Another interesting facet of Nehru’s India is the way it approaches the claim of India’s socialism, which overlaps with the myths of Nehru being the ‘architect of postcolonial India’ and of the Indian state being a strong one. India under Nehru, the author argues, did officiate socialism but it was a socialism of scarcity or even self-help. ‘Every wish, every need, every plan, every programme, had to contend with the ubiquitous sense that there was not enough money for it,’ Sherman writes (87-88). By situating the socialist framework within India’s postcolonial landscape, Sherman delineates it from the Soviet socialist model. In doing so, she illustrates the failures of a decentralised economy where the state was motivated to reduce the gap of unequal distribution through ‘benevolent developmentalist ends’ but never challenged the private industrialists who insisted on running their own show.

Ultimately, Sherman argues that the seven myths that defined early independent India can be better understood through the projects that were undertaken as part of these underpinning ideas. The successes and failures of those projects – previously unaccounted for or conveniently dropped to preserve a ‘thundering Nehru aura’ propagated by his party members, the opposition and the media – is problematised by Sherman to make sense of India’s contemporary political landscape. Sherman suggests that the over-reliance on Nehru in contemporary debates on India’s past, by critics and admirers both, is not designed to illuminate the past but rather to further political aspirations. In doing so, Sherman refuses to accept the binary adopted by parties from all political hues that either puts Nehru on a pedestal or blames him for all failures. Instead, her approach humanises the man behind Nehru’s image, his life and legacy.

As a scholar working on this very timeline, the book changed the ways I perceive Nehru’s India. Sherman’s premise of a history in seven myths serves as an unconventional guide for postcolonial scholars on how to circumvent the limitations of tracing a history when the leader under examination is the only available source in most cases. Nehru’s India demonstrates how to do this through alternative characterisations of the era.

Benefitting from in-depth research across archives in India, the UK and US and sourcing material from official as well as non-official depositories and informal collections, Nehru’s India raises a plethora of unanswered and overlooked questions, offering a promising reimagination of India during its formative years. It is a seminal book to return to and draw inspiration from for reimagining historiography and conceiving contemporary discourse on India. Since Sherman mentions that the inception of Nehru’s India lies in her prior research into secularism in early India, I intend on reading her previous book, Muslim Belonging in Secular India, next.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Banner image credit: Image by Sambeet D from Pixabay.

What an incredible read! 👌