Co-creativity and collaboration

It’s been a playful few weeks in LTI, starting with Chrissi Nerantzi from Manchester Metropolitan University presenting a workshop on playful and creative learning in HE.

Chrissi’s workshop was full of exercises designed to get people moving, thinking and talking with others. She started off by pointing out that being creative doesn’t always mean coming up with something completely original, as remixing, adapting and taking ideas into another context is also creative. We discussed the fact that the majority of learning theories omit the emotional and physical aspects of the learning process. We were asked to think about what we enjoy about teaching and also to discuss our failures and what went wrong for us when teaching recently. Talking this through with another person and getting feedback on what intervention would help was very useful and illustrated that we probably don’t spend enough time sharing and getting feedback on failure and yet this is where we can learn the most.

Chrissi’s workshop was full of exercises designed to get people moving, thinking and talking with others. She started off by pointing out that being creative doesn’t always mean coming up with something completely original, as remixing, adapting and taking ideas into another context is also creative. We discussed the fact that the majority of learning theories omit the emotional and physical aspects of the learning process. We were asked to think about what we enjoy about teaching and also to discuss our failures and what went wrong for us when teaching recently. Talking this through with another person and getting feedback on what intervention would help was very useful and illustrated that we probably don’t spend enough time sharing and getting feedback on failure and yet this is where we can learn the most.

Chrissi recognised that sometimes it can be hard to make large scale change in institutions and gave some personal examples of the barriers and blockers that she has experienced but she also demonstrated that by taking a playful approach to your teaching and making small changes you can create a positive environment which encourages learners to experiment, be creative, try things out and get feedback.

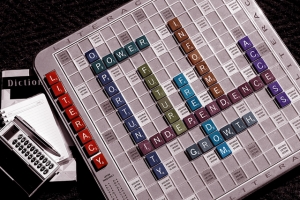

Following on the theme of play and creativity, this week I went up to Coventry University to attend RemixPlay2, a summit to celebrate the design and application of all things gameful, playful and creative in Higher Education. This is the second year of the event hosted by the Disruptive Media Learning Lab in Coventry University (see my blog post on last years’ event). This year’s focus was on co-creativity and collaboration. With similar messages to Chrissi’s workshop on taking an experiential approach to learning by doing, there were a lot of examples of how playful activities and games can be embedded within courses.

Following on the theme of play and creativity, this week I went up to Coventry University to attend RemixPlay2, a summit to celebrate the design and application of all things gameful, playful and creative in Higher Education. This is the second year of the event hosted by the Disruptive Media Learning Lab in Coventry University (see my blog post on last years’ event). This year’s focus was on co-creativity and collaboration. With similar messages to Chrissi’s workshop on taking an experiential approach to learning by doing, there were a lot of examples of how playful activities and games can be embedded within courses.

Ross Flatt from the Institute of Play in New York has worked with a lot of teachers to transform their practice and was an advocate of involving students in the design process and using games as tools for assessment. Sylvester Arnab’s in his keynote argued that the word ‘Fail’ should be defined as ‘First, Attempt In Learning’. He has worked with staff and students on several interdisciplinary projects to try and solve problems in the community. Sylvester has found that by giving students a sense of purpose and encouraging them to think creatively about how they can use what they have learnt to change the world for the better, they are more likely to engage and be motivated to learn. Changing assessment to problem or project based tasks provides students with an intrinsic motivation and shifts the focus away from learning just for passing exams.

Both events provided a lot of inspiration and ideas on the ways we can transform teaching and assessment to be more creative and collaborative. If you are interested in finding out more about using games for learning, we are holding a workshop on designing games for learning on Monday 26 February book a place via the training and development system.

We are starting a community of practice for anyone at LSE who is interested in playful and game-based learning in HE. If you are interested in joining please contact LTI.Support@lse.ac.uk.

If you have an idea on how to make your teaching more playful, creative or game based and would like some funding to support the implementation and evaluation we are currently accepting proposals for Spark and Ignite grants, the deadline for applications is Friday 2nd March, contact s.ney@lse.ac.uk for more information or to discuss your idea.