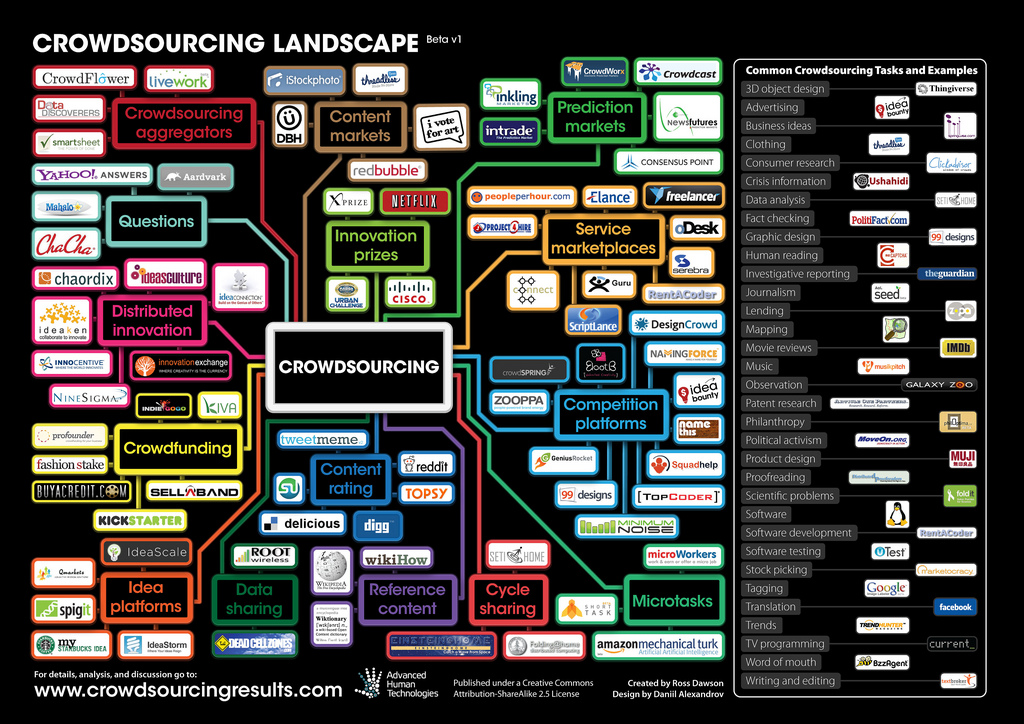

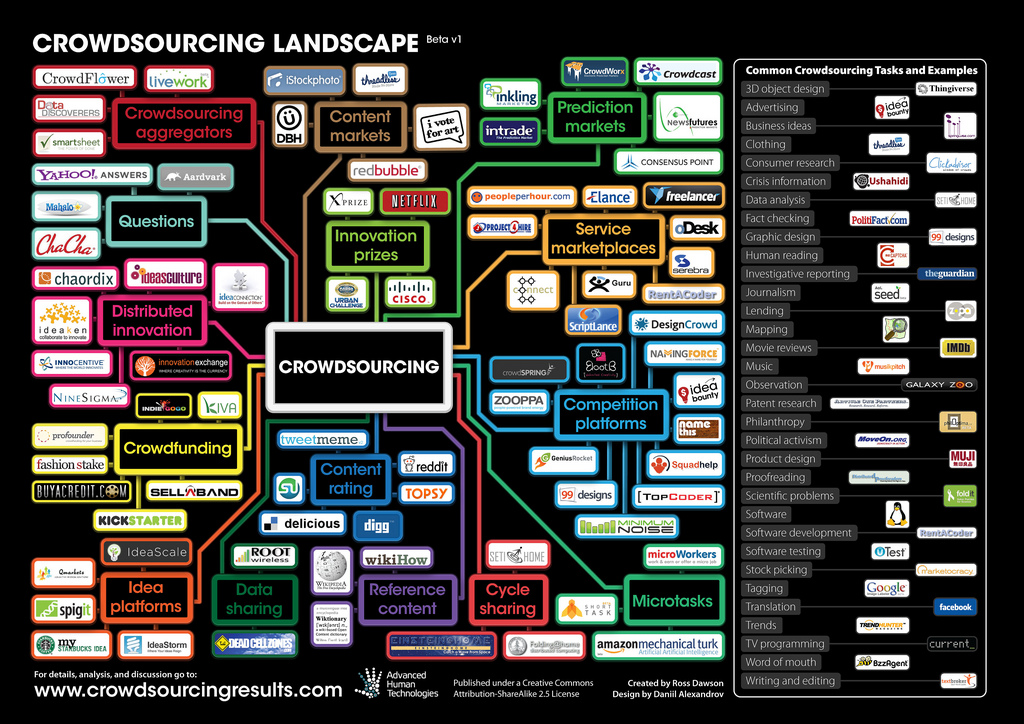

In January 2015, the London School of Economics and Political Science, through the Institute of Public Affairs, launched the third stage of an innovative civic engagement project which aimed to crowd source the UK Constitution. Involving over 1500 participants, generating hundreds of ideas and thousands of comments and votes, the crowd generated the clauses of the constitution, commented on them, voted them up and down, debated the relative merits of competing clauses and then refined them to a manageable number that could be aggregated and argued at a constitutional convention in April 2015.

‘On the whole I found the experience very stimulating and to discover there are a lot of folk out there who are thinking along very similar lines to my own leads me to hope that such exercises are the seed to seeing real change in this country.’ (Comment from project participant)

Learning Technology and Innovation came into the Constitution UK project in September 2014 to pilot an innovative model of engagement and participatory online learning that challenges the dominant paradigms of on-line pedagogy and design. Our approach is built on the potential that exists in leveraging and magnifying the power of the community and the ‘massive’, in order to empower citizens to engage in debate and identify solutions to what may be intractable, impossible or controversial problems or challenges. Our approach is informed by some detailed theoretical and practical interrogations of a number of conceptual frameworks such as peer learning, incidental learning, digital pedagogies, crowd learning and ideation. It also integrates some aspects of modern digital pedagogy such as hacktivism, making and digital citizenship (especially in terms of participatory democracy), exploring the notion of learning as incidental, tacit and exploratory. There were no readings, there was no ‘course’, no lectures, no explicit theories, just a series of challenges, a semi-gamified process of engagement and a framework to create, motivate and empower the community to make something based on what they knew and had learnt.

‘Many other participants were considerably more educated than I am, and I don’t usually get the opportunity to attend things like this, while I expect it is more normal for the (large!) group of people who had postgraduate degrees. It was wonderful to be included’ (Comment from project participant)

Our approach challenged the role of the institution and the academic in an open space. The ‘traditional’ constructs and practices that define scaffolded learning, course design and pedagogy and constructive alignment were flipped to entrust learning to an engaged, creative and critical community. The project was underpinned by an innovative pedagogical model, informed by the notion that learning can occur through a variety of informal engagements and activities, supported by both peer and academic interaction, but not privileged by either, effectively flipping the role of the academic and academy. The environment in which people could choose to learn and/or apply their learning was relatively unstructured, fluid and under the control of the community.

‘There are issues about the fact that the technology privileges people who have access and time to take part, which needs to be addressed. There are other ways it could be developed, but generally I think this is a very positive and exciting initiative. I do think universities should be doing this kind of thing, and more of it.’ (Comment from project participant)

This pilot led to some interesting observations about the model we were testing, especially regarding what is defined as participation and how deep or resonant (lasting) that participation was.

1. Harnessing slacktivism and/or clicktivism

The fleeting nature of mainly online interactions through social media is directly apparent in engagement statistics around MOOCs. What constitutes involvement can be measured in single clicks. In a community where participation started at the point where competing ideas and perspectives were voted up or down in hopefully informed ways, the depth or resonance of learning becomes an interesting question. Modern educational lore (especially in the MOOC space) argues that ‘being there’ is an educationally valid a form of participation as ‘learning there’. Certainly a challenge for our approach was harnessing the power of clicking, hacking and slacking within a community, or at least accepting that there may be learning informing those behaviours. The game aspects of our model rewarded a more in-depth engagement, but towards the end of the project where motivation and participation had begun to wane, rewarding clicking (through the mechanism of up/down votes on an idea) increased overall engagement with the project as opposed to the more traditional trail off.

2. Social observability (where the more public the engagement, the more there is observable ‘subsequent meaningful contribution’ (Kristofferson et al., 2014)

Where learning was demonstrated by participants in the project, it was clearly in the glare of the public and open to the community to comment. One of the key aspects of the model was to make it easy not to lurk. Barriers to entry were low, it was easy to post, comment and vote. In fact, despite expectations before the project, we found it easier to generate ideas than to get votes! But most importantly, it was safe community, with excellent facilitators, a wide variety of participants from a number of fields of society and a very gands off approach by the academics. Ideas became comments which became votes, flipping engagement from the traditional . Having their idea voted down didn’t stop people from participating. Openness, transparency and authenticity of interaction directly enhanced the quality of the ways people demonstrated their learning and (sometimes vocally) expressed their views and ideas. It is what makes collaborative learning powerful, the ability to share your views, debate, defend, redefine and restate them in the face of competing and supporting opinion. It is a 21st century skill of sorting and validating the relevant from the sea of information (in this case the millions of words on the platform)

‘Community members were surprisingly good at separating their own views (I voted this idea down) from the broader task (but the community supports it, so what is a workable provision). Debate was generally high quality and respectful, with many very well informed participants.’ (Community from community participant)

3. Keep the involvement of the crowd at the highest possible level

Wherever ‘traditional’ educational assumptions pervaded the pilot, it was clear that these ran counter to the wider intentions of the approach. The approach sought to value the crowd, leverage what it means to be part of a community and learn incidentally and through doing.

‘…have noticed there was a tendency to assume only academics could properly understand and assess the issues, a common problem not just with academics but other professionals, we tend to assume it is only our own professions that can really grasp the issues in full.’

The Constitution UK was a brilliant first pilot of what we hope will be an innovative programme of projects harnessing the power of the crowd, learning by, through and from the community in ways that challenge and shape the traditional approaches to pedagogy and leverage the transformative and disruptive influences of the social sciences.

We are presenting the findings from the pilot at three conferences over the next four months, if you are interested in finding out more, we will be sharing the slides, papers and outputs from those conferences on this blog, or just come along and see what we have to say.

Academic Practice and Technology Conference – July 7th 2015

Crowd Sourcing the UK Constitution – Participation and learning in a post-digital world

ALT-C – Association of Learning Technology – September 2015

Stop making sense: Learning, community, digital citizenship and the massive in a post-MOOC world

14th European Conference on e-Learning – ECEL 2015 – October 2015

Disrupting how we ‘do’ learning through participatory social media: a case study of the Crowdsourcing the UK Constitution project

‘The experiment gave this 85 year old retired professional engineer a feeling that there’s hope for Britain yet’ (Comment from project participant)

Image from https://www.flickr.com/photos/phauly/5146322288