A new series of updates about emerging trends in learning technology and digital literacy

A guide on teaching with tablets

By 2017, half of the British population will use a tablet*. The device has found its place in many households, but how is it – or can it be used in the context of teaching and learning? Prof. Frank Cowell, winner of an LTI grant, and his Research Assistant, Xuezhu Shi looked into how tablets could be used by teachers in their lectures and devised a guide to help them select the right material and tools to use them as a “virtual chalkboard”

By 2017, half of the British population will use a tablet*. The device has found its place in many households, but how is it – or can it be used in the context of teaching and learning? Prof. Frank Cowell, winner of an LTI grant, and his Research Assistant, Xuezhu Shi looked into how tablets could be used by teachers in their lectures and devised a guide to help them select the right material and tools to use them as a “virtual chalkboard”

Watch the recording of NetworkEDGE Professor Sonia Livingstone 25/02/15

Powerpoint slides from the presentation: Sonia Livingston @ NetworkEDGE – Slides

Tweet your questions and join the debate #lsenetEDGE

Open data & education – hacking the archive

Our NetworkED seminar with Marieke Guy on 26 November was on open data in education. Marieke gave a broad overview of the topic of open data, discussing the different ways that open data is currently being used, who is using it and how it could be used in the future. Marieke gave lots of interesting examples of projects that have used open data and pointed out various open data tools such as Histropedia which allows users to timeline and tag data from Wikipedia or equipment.data which allows HE institutions to sharing educational equipment and facilities.

One of the most interesting aspects of the talk for me was the idea that we should be doing more with open data in the classroom. Marieke advocated using real data sets in teaching and learning as a way to engage students and get them to apply concepts, theories and critical thinking to real world issues and to help them develop their digital literacy skills. This leads in nicely to our upcoming NetworkEDGE seminar with Professor Matthew Connelly which will be on ‘hacking the archive’.

Professor Connelly will be talking about his course ‘HY447 – Hacking the archive’, which uses big data from various International History databases and teaches students new tools and techniques to explore various the vast array of material available online. Students are encouraged to rethink historical research in the digital age as older primary sources are increasingly becoming available online alongside newly declassified information and ‘born digital’ electronic records. Interdisciplinary research is becoming more essential with academics collaborating across disciplines and with the broader public in order to mine extensive amounts of online data.

Matthew will be speaking at NetworkEDGE on Wednesday 14 January 2015, at 5pm

The event is free to attend but places are limited so will need to be reserved via the staff training and development system or by emailing imt.admin@lse.ac.uk. All our talks are live streamed and recorded for those who can’t make it.

The event is free to attend but places are limited so will need to be reserved via the staff training and development system or by emailing imt.admin@lse.ac.uk. All our talks are live streamed and recorded for those who can’t make it.

See the slide share of Marieke Guy’s presentation here: http://www.slideshare.net/MariekeGuy/edtalk2 and go to the LTI Youtube channel for the video of the event and to watch previous NetworkED and NetworkEDGE seminars.

Weekly Roundup in Education Technology: Action Games and Learning, Openwashing and more

Open data or openwashing? – Audrey Watters

Open data is undoubtedly a hot topic, raising issues that go beyond just technology and stretch to education, privacy, human rights, transparency and many other topics. Our event with Marieke Guy today (livestream available; see also our Q&A on open data) will be touching upon some of the relevant issues when discussing open data in education.

In a timely intervention, Audrey Watters criticises the ambiguity attached to the word “open” and highlights the frequent abuse of this ambiguity for business purposes (“openwashing”):

We use “open” as though it is free of ideology, ignoring how much “openness,” particularly as it’s used by technologists, is closely intertwined with “meritocracy” — this notion, a false one, that “open” wipes away inequalities, institutions, biases, history, that “open” “levels the playing field.”

If we believe in equality, if we believe in participatory democracy and participatory culture, if we believe in people and progressive social change, if we believe in sustainability in all its environmental and economic and psychological manifestations, then we need to do better than slap that adjective “open” onto our projects and act as though that’s sufficient or — and this is hard, I know — even sound.

Is it time to start the debate about what we mean by “open” with the larger picture in mind?

Mapping Change: Case Studies on Technology Enhanced Learning – UCISA

This report (the full version of which is available here) presents case studies of institutional approaches towards technology enhanced learning across the United Kingdom. One of the themes emerging is the increasing importance of assessment with technology; an area that we will be covering in more detail on this blog in the weeks to come. Rather than just streamlining procedures and reducing administrative efforts, technology can support new pedagogic approaches and assist in improving the quality of assessment significantly. For a first glimpse into the efforts undertaken by LSE in this field have a look at our summary on LTI’s latest Show&Tell on assessment with technology.

Innovating Pedagogy 2014 – Open University

This year’s report by the Open University highlights ten trends in education for many of which technology is either an integral aspect or can enhance the learning experience. Whether learning through storytelling, massive open social learning (post the MOOC-hype), flipped classroom or any of the other trends address, the report makes for interesting reading and offers plenty of topics for further discussion and analysis.

Information and digital literacy: It’s not all about technology – CILIP Information Literacy Group

Responding to the interim report on “Digital Skills for Tomorrow’s World” by the UK Digital Skills Taskforce, LTI’s Jane Secker and Stephane Goldstein from InformAll pose a perhaps somewhat unexpected criticism. While generally praising the report and its intention, they criticise it for focusing too heavily on technological skills:

We feel that this suggests too narrow an approach to the relationship that individuals, in a knowledge-based society and economy, need to develop with information.

Instead, they argue for a broader definition of digital and information literacies, which encompasses the skills needed to survive in the digital world:

Equipping people with the knowledge, understanding, skills and confidence that they need to search for, discover, access, retrieve, sift, interpret, analyse, manage, create, communicate and preserve ever-increasing volumes of information, whether digital, printed or oral

Headshot: Action video games and learning – Gizmag

Few of us would think of action video games as improving our learning. Perhaps even too few of us? This recent study suggests a link between action games and the development of learning capabilities. It will be interesting to observe when (and if) education seizes the potential offered by games for both learning and learning capabilities on a larger scale.

* Education technology is rapidly moving, sometimes divisive and always interesting, especially to us working in Higher Education. Every week, we share and comment upon a selection of interesting articles, posts and websites relating to education and technology we stumbled upon during the week. Do comment, recommend and share!

Q&A with Marieke Guy

You can watch the video recording of the Marieke Guy NetworkED seminar on our LTI Youtube channel and a Q&A with Marieke can be found below

- Marieke Guy from Open Knowledge

Ahead of her NetwokED seminar talk on Wednesday 26 November Marieke Guy answered some questions for LTI on open data in education.

Q1. How would you define ‘open data’? How does this relate to ‘open access’ and ‘open education’ ?

We’re very lucky to have an excellent definition of open data from Open Definition, which specifically sets out principles that define “openness” in relation to data and content:

“Open means anyone can freely access, use, modify, and share for any purpose (subject, at most, to requirements that preserve provenance and openness.”

So we are talking about data that is available for people to access and can be reused and redistributed by everyone. One of the important points to make is that openness does not discriminate against commercizal use. Open data is definitely a friend of open access and open education! Publicly funded research publications should not only be open access but the data behind them should also be shared and openly available. At the Open Education Working Group we see open education as a collective term that is used to refer to many practices and activities that have both openness and education at their core. Open data is an important area, along with open content, open licensing, open tools, open policy and open learning and teaching practices. This is becoming even more the case with the rise in online learning, MOOCs and the use of learning analytics.

Q2. Who typically uses open data and what does it get used for?

Anyone can consume open data as an end-user benefitting from openness, but there are two main groups who have a specific interest in dealing with open data. Data providers (such as the government or your institution) may be interested in releasing and sharing data openly. Data handlers are interested in using the data available, maybe by developing an app or service around the data, or by visualising the data, or by asking questions of the data and mining it in some way. A nice easy example here is the Great British Toilet map,

where government data was combined with ordnance survey and open street map data to provide a public service app that helps us find the nearest public convenience. You can also add toilets you find to the map, allowing the data that is available to be improved on.

Obviously people who want to get their hands messy with data will need to be data literate. One of our core projects at Open Knowledge is School of Data. School of Data works to empower civil society organisations, journalists and citizens with the skills they need to use data effectively in their efforts to create more equitable and effective societies.

Q3. What are the pros and cons of open data?

The main benefits for using open data are around transparency (knowing what your government and other public bodies are doing), releasing social and commercial value, and participation and engagement. By opening up data, citizens are enabled to be much more directly informed and involved in decision-making. This is about making a full “read/write” society, not just about knowing what is happening in the process of governance but being able to contribute to it.

Opening anything up makes organisations more vulnerable, especially if they have something to hide, or if their data is inaccurate or incomplete. There is also a cost to releasing and building on data. Often this cost is outweighed by the social or economic benefit generated, but this benefit can develop over time so can be hard to demonstrate. Other challenges include the possible misinterpretion or misrepresention of data, and of course issues around privacy.

I personally see open data as being in the same space as freedom of speech with regard to these challenges. We know that open data is the right way to go but there are still some subtleties that we need to work out. The answer to a ‘bad’ use of open data is not to close the data, just as the answer to a racist rant is not to remove our right to freedom of speech.

Q4. Do you have any examples of projects that have involved using ‘open data’ and if so what advantage did ‘open data’ bring?

Earlier this year Otavio Ritter (Open education data researcher, Getulio Vargas Foundation, Brazil) gave a talk to our Open Education Working Group. He mentioned a case in Brazil where the school census collects data about violence in school area (like drug traffic or other risks to pupils). Based on an open data platform developed to navigate through the census it was possible to see that in a specific Brazilian state 35% of public schools had drug traffic near the schools. This fact put pressure on the local government to create a public policy and a campaign to prevent drug use among students. Since then a collection of initiatives run by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) have made a huge impact on the drug traffic levels near schools.

Q5. What does Open Knowledge do?

Open Knowledge is a worldwide non-profit network of people who believe in openness. We use advocacy, technology and training to unlock information and enable people to work with it to create and share knowledge. We work on projects, create tools and support an amazing international network of individuals passionate about openness and active in making, training and promoting open knowledge. Our network is global (we have groups in more than 40 countries and 9 local chapters) and cross-domain (we currently have 19 working groups that focus on discussion and activity around a given area of open knowledge).

Marieke Guy will be talking at LSE on Wednesday 26 November at 5pm in NAB2.06. To book your place go to the staff training and development system or (for those without access to the system) email imt.admin@lse.ac.uk

Have a look at previous talks on our Youtube channel.

Students and smartphones: it’s too late to lead the horse to water, but you can certainly make it learn

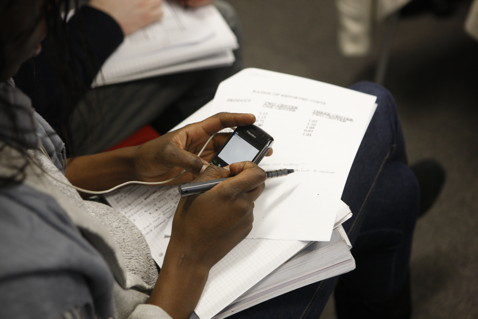

Recently, an article by Tosell et al (2014) titled You can lead a horse to water but you can’t make them learn: Smartphone use in higher education has stirred some debate on the topic in email lists and forums in the learning technology world. After giving 24 students iPhones and monitoring their activities using an in-built app and two surveys taken a year apart. The authors found that students felt their iPhones were an unwelcome distraction, contrary to students’ initial belief that smartphones would help in their learning a year later.

The knee-jerk reaction to this finding would be to ban smartphones and devices from the lecture hall and classroom. But with 92% of students reporting to own such a device in our 2013 student survey, that may not be feasible. It’s too late to stop the horse from bolting, and smart devices in lecture theatres and classrooms are here to stay.

92% of students in our 2013 student survey reported owning a smartphone in 2013. Smart devices in the classroom are here to stay. Image copyright: ©2011 LSE/Nigel Stead, all rights reserved.

Banning smart devices from the lecture hall is also not the conclusion Tosell et al come to. The paper itself is a nuanced, well written article, with interesting methods of measurement (albeit with quite a small sample of students without a control group, which the authors do caveat).

What the authors have highlighted, is that providing smart devices to students in an unstructured way and simply expecting students to use these devices for their learning won’t lead to better learning outcomes, and could even be detrimental to learning. This doesn’t seem too surprising, considering Margaryan et al (2011) suggested that even “digital natives” (a contentious term in it’s own right), “…have a limited understanding of how technology may support their learning”. Indeed, White et al (2012) point out that many students gain digital literacy skills, which include using smart devices for learning, through trial and error, without the support of the institution.

Of course, students may not even want to use smartphones for their university work. The authors found that 90% of the apps installed on the iPhones given to students had nothing to do with their courses, and 65% of apps launched were communications or social media apps. Smart devices, smartphones in particular, occupy several important roles in the lives of students, the primary one being the ability to communicate with peers, friends and family. Indeed, a third of students in our own student survey claimed they were uncomfortable with the idea of using their device for university work, highlighting student concerns about managing personal and academic lives in an increasingly connected setting.

Therefore both students and teachers need to evaluate what these devices could bring to them in the classroom. Lecturers could encourage students to use their devices in more positive ways in the classroom, by encouraging the use of smartphones for in-class activities such as voting, fact-checking using the internet, collaboration through social and digital note-taking. Students also need better support and advice from universities on how they could use smartphones and devices for their learning and manage their personal activities.

What’s disputable is that smartphones are simply a distraction, and that students are unable to have a smartphone in class and be able to learn in class. Smartphones and devices are just the latest in a long line of distractions which have diverted students’ attention from the lecture. Ultimately, engaging and accessible teaching and content is what is most likely to stop students from getting distracted in class. What’s more important here is how smartphones and devices could be used in lectures and seminars to engage students better. Tools for engaging students using smart devices already exist, and if harnessed appropriately, smartphones and devices could transform the teaching and learning experience for both lecturers and students, rather than simply be the latest distraction.

References:

Margaryan, A., Littlejohn, A. & Vojt, G. (2011). Are digital natives a myth or reality? University students’ use of digital technologies. Computers and Education, 56, 2, 429–440.

Tossell, A., Kortum, P., Shepard, C., Rahmati, A., Zhong, L. (2014). You can lead a horse to water but you cannot make him learn: Smartphone use in higher education. British Journal of Educational Technology. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12176

White, D., Connaway, L. S., Le Cornu, A., & Hood, E. (2012). Digital Visitors and Residents Progress Report (pp. 0–40). Oxford, Charlotte. Retrieved from http://www.jisc.ac.uk/media/documents/projects/visitorsandresidentsinterim report.pdf

Good news: Learning technology not rocket science!

I’ve been a learning technologist since 2002, at the LSE since 2009. Ten years ago I presented a short paper at a conference about the purpose of the learning technologist, because even we as a group didn’t really know. It’s only short and it ends with a suggestion that what we learning technologists should be doing is stamp on people’s toes, and so it is, if not agreeable, still interesting, and still relevant. If you’re in the mood for speculative musings on what learning technology is about, give it a read: ‘What are we for?‘.

Fast forward ten years and puzzlement as to what we do or what we are for remains. That’s fair enough, after all, if you’re an engineer and you meet someone who tells you they are a dentist, you would also ask “oh, dentist, I see, but what does that mean, I mean what do you actually do?” And so with Learning Technologists. We’re a bit like dentists. Unfathomable. Mysterious.

I’ll try once more to lift the lid on that mystery.

Here’s the good news: what we do is really easy to understand, you just have to be prepared to listen. To prove this, and to allow for different tastes and learning styles, I offer you three different explanations, with the keywords highlighted, so you can skim through.

1. Generic: in short

Here’s a generic overview of what LTI (found on our LTI page):

“Learning Technology and Innovation (LTI) supports staff in the use of technologies to enhance teaching and learning at the London School of Economics. We […] promote the integration and use of technology in teaching and learning by supporting key technologies, through staff development, advice and guidance, research, collaboration and networking.”

Put differently: we provide pedagogical support and guidance to academic teaching staff with a focus on technology.

Or as a question: How can technology help improve your teaching and your students’ learning? We’re here to find out for and with you.

2. Concrete: drilling down

Academic staff (incl GTAs) are our core focus, but in many cases we deal with administrative staff too, especially in dealing with routine queries about setting things up in Moodle, or using TurnItIn and so on. We write materials too, from basic training materials, to guides on how to use educational technologies, to policy and guidance documents on copyright for example. A large part of our work is staff development. We develop and run workshops on the use of educational technologies – each of which will always incorporate theoretical discussions on how these might impact on student learning. We work closely with TLC, and teach about learning theories on the PG Certificate in Higher Education. We do research – you can’t really expect to persuade academics at a research intensive university about the benefits of changing practices, adopting different pedagogical approaches, trying out technologies etc if we didn’t. We read up on what’s new, engage with our colleagues across the UK and further afield. We make connections with interested teachers and persuade them to try new things – that is, we track them down and buy them coffee and have exciting chats and then we hit them over the head with a mallet and force them to do a pilot with us. Maybe with clickers, or iPads, or flipping lectures or eAssessment.

3. Contradictory: we are not

We are not a lending service. So you want to borrow an iPad from us to see what it can do? Of course you can. First of all, we are super approachable and we all tend to say yes rather than no. Nevertheless, there should always be a “using it for teaching” aspect.

We’re not IT training. While our workshops have elements of ‘hands on how to use technology x’, the main emphasis is on how it impacts on teaching and learning, how best to use the technology in a teaching and learning context. Most of our workshops are discursive.

We are not technical support. Most of us are pretty tech savvy, but all of us focus on impact that technology (as concept) and educational technologies.

See, that wasn’t so hard. And one of these days dentists will be equally well understood.

Cursive or keyboard? Is note-taking the issue here, or pedagogy?

Recently, Mueller and Oppenheimer (1) published an interesting paper in the journal Contemporary Educational Psychology titled The Pen Is Mightier Than the Keyboard: Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking. In the abstract of the paper, Mueller and Oppenheimer, claim:

We show that whereas taking more notes can be beneficial, laptop note takers’ tendency to transcribe lectures verbatim rather than processing information and reframing it in their own words is detrimental to learning.

What was concerning, however, was the final sentence of the paper which said:

For that reason, laptop use in classrooms should be viewed with a healthy dose of caution; despite their growing popularity, laptops may be doing more harm in classrooms than good.

While the study showed that there was improved memory retention and test scores through longhand note-taking, it seemed a little strong to conclude that “laptops may be doing more harm than good” in classrooms. There are practical reasons why student device ownership and use in classrooms has increased in recent years, and what is lost in this statement, are the benefits laptops and other devices offer to students, and why they’re used in lectures and seminars in the first place.

Not all note-takers are created equal

Note-taking is a fundamental part of students’ learning experience at university. In their paper, Mueller and Oppenheimer have a point that making more notes doesn’t mean making better notes and mindless verbatim note-taking does little to reinforce concepts. Indeed, they allude to an interesting argument that handwritten notes may involve more cognitive processes, allowing concepts to better embed themselves into memory, leading to an improvement in conceptual learning from lectures.

However, note-taking as a skill is rarely ever taught, and students are expected to know how to take notes in a lecture format, which, to many undergraduate students in particular, is an alien concept coming from classroom environments. Longhand note-taking is particularly problematic for students with neurodiverse conditions and learning disabilities. Williams (2) found that 56.4% of students with learning disabilities out of a cohort of 642 students were unable to take notes during live lectures, and technical solutions such as laptops can be a lifeline to these students to be able to better interact with lecture and class materials.

Indeed, Bring-your-own-device (or BYOD), particularly laptops, amongst students are almost ubiquitous, with 99% of LSE students reporting to own at least a laptop, and 62% of students willing to use laptops during class (3). Some of the reasons why students use laptops in lectures to take notes is that longhand notes don’t have the durability of typed notes, which can be standardised through font, magnified, highlighted and edited for greater legibility, printed, stored and accessed in multiple places using free and easily accessible services such as Dropbox and Google Drive.

Typed notes are also more easily shared and remixed amongst peers using email, social media, Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs) etc. Digital notes can be directly linked to lecture slides, lecture recordings, related journal articles, blogs, media images and videos, all of which can not only help contextualise the notes, but also expand their scope by bringing in resources outside of the lecture theatre.

Even in today’s hyper-connected world with students having almost ubiquitous access to laptops, smartphones and the internet, students will still make notes by hand out of for a number of reasons, including preference. But, there doesn’t need to be a dichotomy between typing and writing, as solutions exist which bridge the gap between digital and longhand note-taking. Tablets and smartphones now offer several apps which allow handwritten notations to be made on digital documents for free or a nominal cost. Apps, such as Paper for the iPad, also allow students to create drawings and charts, which could be stored in cloud services and shared with peers through some of the media mentioned above.

Is note-taking really the issue here?

Perhaps, the point here is not that note-taking is better done by hand, but perhaps that student practices are changing as devices such as laptops, tablets and smartphones offer significant functionalities in lectures and classrooms which may not fully utilised by the pedagogical models used in lectures. Students not paying attention and not making effective notes is by no means a new concept, as any teacher throughout the ages would testify.

The lecture is an ancient method of teaching, and students not paying attention is not a new phenomenon. Perhaps it’s the passive nature of the lecture which drives students to distraction rather than the device itself?

Sourced under Creative Commons license from The Yorck Project: 10.000 Meisterwerke der Malerei. DVD-ROM, 2002. ISBN 3936122202. Distributed by DIRECTMEDIA Publishing GmbH.

Students that are interested and engaged in the lecture material are less likely to drift off, whether it’s by doodling on their notepads or checking their Facebook feed. What these powerful tools in students’ backpacks and pockets offer is the potential to go beyond passive note-taking, and in to active, connective learning. Therefore, instead of banishing laptops and devices from lecture theatres, lecturers could think about using their students’ connectedness to their advantage, by getting students to use laptops and other devices to better interact with course materials and play around with concepts, rather than passively absorb what the lecturer says over a period of several hours.

Thoughts?

Leave a comment!

References

(1) Mueller, P.A., Oppenheimer, D.M. 2014. The Pen is Mightier than the Keyboard. Advantages of Longhand Over Laptop Note Taking. Psychological Science 23;25(6): Pp. 1159-1168

(2) Williams, J., 2006. The Lectopia service and students with disabilities. In Proceedings of the 23rd annual ascilite conference: Who’s learning? Whose technology? Ascilite 2006. The University of Sydney. Sydney, pp. 881–884.

(3) Grussendorf, Sonja (2013) Device ownership, ‘BYOD’ & social media for learning. Centre for Learning Technology (CLT), The London School of Economics and Political Science, London.

Trends in Educational Technology report

Over the past few months, CLT have been looking into some of the key technological trends set to influence the higher education sector in the next few years. We looked at the benefits they may provide to teaching and learning at LSE (and indeed, other institutions), and the considerations that need to be made before these technologies are implemented.

Using horizon scanning techniques to identify suitable reports, academic articles, media articles and blog posts by institutions and commentators working in the field, four key technological trends were identified through this method; Massive Open Online Courses (MOOCs), Bring Your Own Devices (BYOD), Gamification and Games-based learning and Learning Analytics.

A report on our research, Trends in Educational Technology, is now available on LSE Research Online. The report argues that these technologies can be beneficial, and should be embraced if they address institutional needs. However pedagogy must be at the heart of any technological adoption.

The summarized findings of this report are as follows:

Going Mobile: the ongoing story of HEC Executive Education

Gerta Karageorgi from the LSE Project Management Office writes about attending an LSE NetworkED seminar earlier this week.

On Wednesday 5th February 2014, Karine Le Joly, Director of Innovation and Academic Coordination for Executive programmes at HEC Paris (Hautes études commerciales de Paris), made a day trip on the Eurostar to LSE to present the 8th NetworkED: Technology in Education session. It was a topic I was keen to learn more about, having spent a day the previous week attending 7 brief seminars on mobile technology at the Learning technologies exhibition at Kensington Olympia, London.