Like many Department of Management students, Srishti Gupta found herself learning many useful new theories – which can be tricky to remember. Here’s Srishti’s explanation of one of the key frameworks: Porter’s five forces.

If you’re a management student, you’re bound to come across Porter’s five forces sooner or later. Chances are that if you’re just starting out in this field, you have no idea as to what it means – and since it’s used so frequently, you might be too embarrassed to ask.

If that’s the case, then you’re not alone. I used to be one of those kids as well. I only encountered the concept in the 11th week of MT at LSE. So, to save yourselves the awkwardness of asking a management fellow, or the pain of going through countless web pages filled with jargon, let’s break down the Porter’s five forces framework, and find out why it’s mentioned in business and management classes so often.

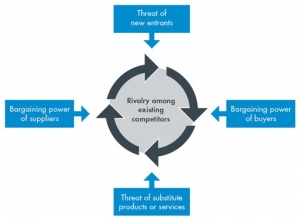

Porter’s five forces is a framework developed by Michel Porter, first published in Harvard Business Review in 1979, to analyse the factors that affect the profitability of an industry. Profitability is affected by the bargaining power of various stakeholders in that industry – the competitors, the suppliers and the buyers. The influence of these stakeholders in the industry are expressed in the form of the five forces listed below. These factors enable a firm to decide whether or not to enter a market.

To make the analysis more relatable, we’ll use the Department of Management at LSE as an example of an ‘industry’ (which is a gross generalization), and a prospective student as the ‘firm’ trying to enter the industry.

Rivalry among competitors: When the competition among firms is high, each firm has incentive to undercut others by reducing prices which in turn reduces the firm’s profits. Rivalry may also manifest in the form of increased costs of advertising. A company in an industry with low competition has greater ability to appropriate the profits generated.

Due to the high volume of applications, the students looking to get into a course in the Department of Management face intense competition right from the start. Each student works to differentiate himself or herself from the crowd in order to be a part of the elite group.

Supplier Power: The more powerful the supplier, the greater their ability to grab a share of the pie of profits. They can achieve this by increasing the prices of the raw material, which in turn increases the overall cost of production of the good. Supplier power can be great if they are the sole supplier of the raw material, or if the good supplied is scarce, or if they deliver a material necessary in the production process of the firm.

The university supplies you with raw material in the form of education. Since the professors and forms of teaching at LSE are unique, its bargaining power is quite high, and it is thus able to charge a high fee for providing us (the students) the raw material.

Buyer Power: The buyer’s power comes from their ability to bring down the prices of the good being sold by the firm. This can happen if the products are being sold to a very small group of customers, or the good is a luxury good or if the consumers have a lot of alternatives they can switch to. All these factors contribute to buyers getting a larger slice of the pie in the form of lower prices, resulting in a greater consumer surplus (because the consumers have been charged a price which is below the maximum price they would be willing to pay for the good).

The ‘buyers’ in our industry would be the future employers. If most graduates get into entry level jobs, and there exist many management students at LSE itself and other close substitutes that the employers can switch to, then this would imply that the buyer power is also strong.

Threat of Substitution: If the good being sold is similar, or worse, identical to existing products in the market, then the product is likely to be priced the same as its competitors. Therefore, companies that pay an increasing focus on differentiating their products in the industry can make a stronger case for charging more for their products, and thus position themselves better in terms of accruing profits.

One could argue that management students from other universities in the UK are viable substitutes for LSE management students. Consequently, it is important that the students differentiate themselves from the rest, to make themselves more attractive in the eyes of the ultimate ‘buyers’ of their skills: the future employers.

Threat if new entry/Barriers to entry: If the industry is very profitable, more and more competitors will want to enter the industry. If it is easy for competitors to enter, then the profits generated will be shared among a larger group of firms, lowering the profit per firm. Hence, an industry with high barriers to entry is better able to sustain its profitability than an industry with low barriers to entry.

In higher education, the barrier to entry is formed by the application process which only takes in a limited number of students each year. This implies that there are relatively high barriers to entry, which works in favour of the students who are in the department.

And there you have it: the five forces analysis for evaluating profitability. With high competitive rivalry, strong position of “suppliers” and “buyers”, moderate level of substitution and high barriers of entry, a prospective student (the lone firm) may be discouraged from applying to the Department of Management at LSE. After all, according to the five forces analysis it might not be profitable.

However, this is not to discourage any perspective student from actually applying – because once you’re in, the profits to be gained are endless.

Learn more about the MSc in Management and Strategy programme

This is very interesting article and application for the five forces. However, the question could be raised here if whether the government force should be considered or not is vital to analysis.