by Sandra Sfeir

In the age of social media, the meme is king. Put simply, a meme is a ‘faddish joke or practice…that becomes widely imitated.’ Commonly taking the form of comics, captioned images or videos, memes are a popular, accessible and satirical means of engagement with the issues of the day, whether serious or light-hearted. They represent, in many ways, the pulse of the internet. The Egyptian ‘memosphere’ – a dynamic virtual space occupied by Egyptian meme-makers and their predominantly local audience – constitutes one of the largest in the region, and its growing popularity and reach invite us to think seriously about the social and political significance of memes.

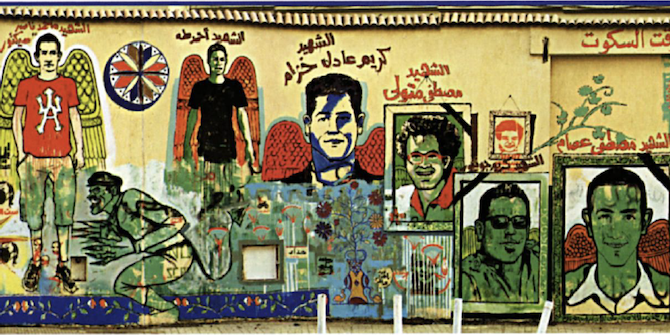

Since the 2011 Egyptian uprising, the breaking of the ‘fear barrier’ has extended itself into the ‘memosphere’. From President Mohamed Morsi to President Abdelfattah el-Sisi and the Egyptian army, meme-makers have spared no-one. The relative anonymity afforded by online spaces has allowed them greater scope to cross the red lines limiting free speech for traditional print and broadcast media.

But why does this matter? The vibrancy of this space speaks to Egyptians’ creative use of new forms of media as everyday tools to both vent their frustration and rail against established power by mocking its most visible manifestations: the state and its representatives. This is especially significant in an increasingly repressive environment in which avenues for subversive self-expression and political participation are ever-shrinking. What makes memes so important both in the Egyptian context and beyond is that they constitute a particularly effective tool for disrupting the state’s attempts to control space (here, in the virtual sense) by monopolising image production and projection, and ultimately to command the narrative. Their use of counter-imagery and narratives also allows memes to retell the story, making politics more accessible to a lay audience and creating new ways of understanding the world.

To illustrate, the below meme, posted in August 2016 on the ‘Asa7be Sarcasm Society’ Facebook page (a page with over 14 million ‘likes’), is captioned: ‘el-Sisi to the people: how can we raise salaries?’

The meme depicts a scene from Egyptian comedy film Abo Ali, where football coach Amin assigns field positions based on the quality of the food his players bring for him. Here, a smiling el-Sisi replaces Amin, doling out pay rises to different ‘players’ in Egyptian society, including the army, police and judiciary. The final frame shows el-Sisi raising a pointed finger at another ‘player’ accompanied by the jibe: ‘What’s this, an ordinary citizen? I swear you won’t see an extra penny for as long as I’m here’.

The images highlight the double standard inherent in the President’s insistence that the state cannot afford to raise public sector salaries, despite having been able to regularly increase the salaries of military personnel, police and judges. It also offers an alternative narrative, suggesting that el-Sisi is prepared to compromise the well-being of ordinary Egyptians to appease those groups on which his strategic interests depend. Notably, the image received more than 91,000 likes, 21,000 shares and over 1,000 comments, as well as generating a flood of reaction memes. Such impressive reach and interaction – as well as the speed with which meme-makers reacted to the President’s remarks – serve as a reminder that the ‘memosphere’ is a space for everyday engagement.

Memes represent an important form of contemporary engagement with politics, and one that should be taken seriously. Presently, academic research into memes is very limited and raises more questions than answers; which groups of people create and consume them? Is there a tangible way of measuring how people interpret and respond to memes? Is the ‘memosphere’ an arena for serious debate, or simply an opportunistic space for self-indulgent humour? These are but a few gaps in knowledge that invite further research into memes and ‘memospheres’, whether in Egypt or elsewhere.

Sandra Sfeir is Events Coordinator at the LSE Middle East Centre. She has a BA in Politics and Economics from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Prior to joining the Centre, she completed an internship at Chatham House’s Press Office and has also worked in Arabic media. She has recently completed her Master’s in Middle East Politics at SOAS.

Sandra Sfeir is Events Coordinator at the LSE Middle East Centre. She has a BA in Politics and Economics from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). Prior to joining the Centre, she completed an internship at Chatham House’s Press Office and has also worked in Arabic media. She has recently completed her Master’s in Middle East Politics at SOAS.

Hurrah! After all I got a web site from where I can actually get useful data concerning my study and knowledge.