by Raad Alkadiri

A ray of hope

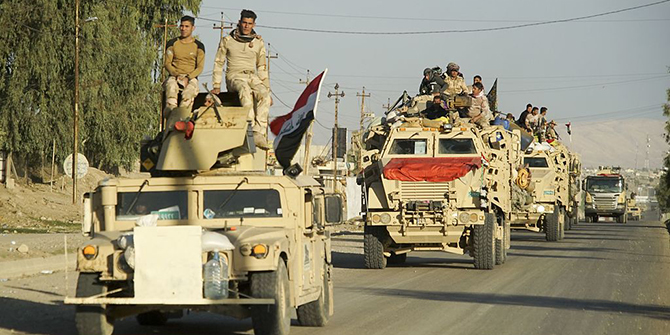

The defeat of Islamic State (IS) in northern and western Iraq, and restoration of federal-government control over disputed territories (including Kirkuk) in the aftermath of the KRG referendum on independence, have altered the mood of Baghdad politics significantly in recent months. There is a tangible new sense of Iraqi nationalism (among Arab Iraqis at least), a sentiment that has been bolstered by Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi’s adroit management of the post-conflict environment. Rather than stoke domestic divisions, Abadi has sought to calm tempers and dampen some of Baghdad’s triumphalism vis-à-vis both Iraq’s Sunnis and Kurds. He is also using his newfound prestige to attempt the reforms needed to win the peace, including renewed efforts to combat corruption.

This change is breeding hope that Iraqi politics is entering a period of real transition as national elections approach in late spring of 2018. The hope is that the polls will usher in a decisive shift away from the corrosive ethno-sectarian system that has shaped Iraqi politics since the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003 towards a less identity-driven framework that prioritises effective governance and genuine power-sharing over communalism. No-one expects identity politics to disappear as a factor in Iraqi politics; rather, the sense is that there is now an opportunity to reorient political debate and action away how power in the country should be divvied up and towards a focus on overcoming communal divisions and improving the administration of the state.

As such, the elections are seen by some as a competition between an existing regime that has dominated – and benefited from – the post-2003 order, and proponents of a new, issue-based politics, the outlines of which have been evident for the past two years at least. Advocates of this view point to recent changes in the Iraqi political landscape, including: the fragmentation of the Iraqi National Alliance (INA), the coalition of Islamist Shia parties that have effectively controlled the federal government over the past 14 years, and the decision of its constituent entities to contest the election either individually or as part of smaller alliances; renewed discussion of creating secular, cross-ethno-sectarian electoral lists campaigning on nationalist or issue-based platforms; the rise in Sunni support for Abadi; and possible fracture of the Kurdish Alliance in the Iraqi Council of Representatives, reflecting inter-party turmoil in Kurdistan.

These recent changes have been accompanied by an apparent shift in popular emphasis towards good governance, rule of law and improved standards of living, less sectarian and more nationalist platforms that Abadi, as well as organisations like the Sadrists and Ammar al-Hakim’s new Hikma party, are seeking to capitalise on. Communal identity remains strong in Iraq; but for many, it is no longer an excuse for accepting bad policy. The Kurdish experience after the referendum illustrates the dangers that popular disillusionment with bad policy poses for established elites, and Kurdistan is not alone; parts of the Shia constituency are now seeking to hold their leaders more accountable for their decisions, elevating the need for good governance above a history of struggle against repression in judging their leaders’ performance. In the process, Shia sectarianism is being replaced by an Iraqi nationalism with a heavily Shia hue.

Déjà vu all over again?

Yet the question remains whether the shifts in Iraqi politics represent the beginning of genuine change, or whether Iraqi leaders are simply paying lip-service to popular demands in a bid to capitalise on post-conflict euphoria for their own ends. Abadi and some other leaders may be genuine in their calls for reform and desire to break with the past. But the real test will be what policy solutions they propose, how they intend to implement them, and, most importantly of all, whether they can dislodge political elites who prerogatives are at risk from any change in the status quo.

After all, Abadi has staked his credibility as prime minister on reform before, only to fail. His efforts in 2015 to combat high-level corruption and break the established parties’ stronghold on government by creating a technocratic cabinet met with fierce resistance from Iraq’s political elite, including many of the same figures who are now claiming to be reformers. Some ministers were changed, but their replacements were chosen by the parties that had controlled the portfolios in the first place. Meanwhile, anti-corruption efforts amounted to little more than an exchange of accusations between Abadi and his biggest political opponents, notably former Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki and his allies. There was no real substantive change: governance remained poor; rule of law continued to be undermined; corruption persisted; and institutions did not get stronger or more effective. At the same time, the government remained dependent on oil-export receipts to pay for a bloated public sector; private-sector activity was anaemic; and the economy struggled to grow.

It is not clear the central factor that undid reform then – the post-2003 elite’s dogged refusal to surrender its stranglehold over politics – is any less potent in 2018, despite the different circumstances. Abadi’s legitimacy and political capital is at an all-time high, especially since the restoration of federal government authority in Kirkuk, and, as such, he has become an independent political force on par with the likes of Maliki and Sadr, as opposed to a face in the elite crowd. The breadth of this popularity – and the fact that he is not Maliki – may be sufficient to win him a second term as premier, but the post-IS/Kirkuk honeymoon he is enjoying will lapse eventually, and his stature – and room for manoeuvre – will be eroded, thereby undermining his capacity to institute meaningful reform in the face of fierce resistance from his foes.

Similarly, it is not clear whether the fragmentation of the INA or other identity-based alliances represents a structural change or is simply a case of campaign tactics. Splits within the Islamist Shia bloc are partly driven by differences over policy and reform; but, equally, they represent personality differences and internal competition as each group attempts to improve its hand in advance of the inevitable post-election horse-trading over government posts. Each party wants to underline its own electoral strength (and seats in the next Council of Representatives) in order to push its claim for the premiership and/or other senior posts; but it is not clear if this is motivated by a desire for power and patronage, or is genuinely an effort to alter policy. One critical signpost of change will be whether the various parties perform fundamentally better or worse than they have in past elections, and whether there is a real change in voting patterns based on policy proposals. If not, the tactical manoeuvring may be little more than moving deckchairs on the Titanic.

The same goes for Sunni and Kurdish parties. The Sunni elite’s narrative of disenfranchisement and repression belies its complete lack of cohesion and its inept political strategy. The community has undoubtedly faced marginalisation in the post-2003 order and has borne the brunt of IS-related violence and destruction. But Sunni leaders have offered few workable policy solutions, and instead of riding the wave of nationalist sentiment and demands for policy solutions, they remain focused on personal rivalries. Calls by Sunni leaders to postpone elections in predominantly Sunni-led provinces are understandable given the huge scale of the reconstruction task in these areas, but it also risks marginalising them further in national politics in a manner similar to their past electoral boycotts. The Kurds meanwhile are consumed by internal rivalries and a political transition that is separating the main parties further from federal politics, and which promises few meaningful solutions to the key fiscal and institutional challenges that must be addressed in order to establish stability in Kurdistan and provide the basis for a long-term settlement with Baghdad.

The importance of institutional reform

The obstacles to a meaningful change in Iraqi politics reflect a structural reality: the balance of power between ‘Green Zone’ politicians handed power in 2003 and wider society remains overwhelmingly in favour of the former. In many ways, Iraq has one of the most representative political systems in the Middle East, combined with a liberal media and open freedom of expression. But the electoral law favours big established parties with leaders that have in most cases been part of the elite since 2003 and who are bent on preserving their own influence and interests; few if any new faces have emerged to challenge the status quo. Meanwhile, the ability of the population to influence policy once elections are over – either through pressure on the government or through the Council of Representatives – is extremely limited. The Council of Representatives, in particular, has become a byword for gridlock and preserving prerogative. Party leaders and their cadres pay lip-service to the need for reform, some more than others; but with the exception of Muqtada al-Sadr, Hakim and Abadi, few have articulated an alternative vision of Iraq, and even in the case of these three men, the gap between action and words is marked.

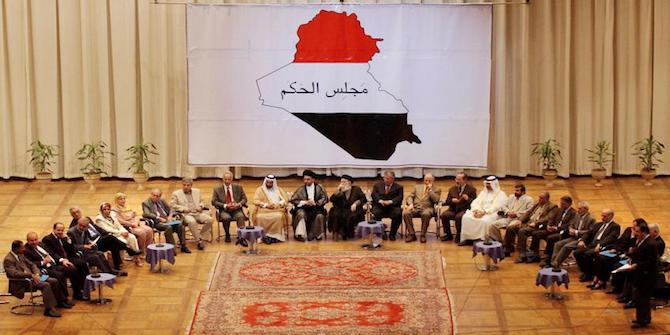

This shortfall reflects, in part, the scale of the challenge – and risks – that genuine reform would entail. The failure of governance in Iraq is not simply a product of poor leadership. It is also a reflection of the hollowed-out institutional system bequeathed to Iraqi leaders by the US-led Coalition Provisional Authority, and its obsession with ethno-sectarian formulae (an approach that was encouraged by Iraq’s new Islamist Shia and Kurdish leaders). The US focus on downsizing the Iraqi state, and its overwhelming emphasis on communal quotas at all levels of government, have tainted governance since 2003, and sowed the seeds of the maladministration, corruption and economic imbalance that plagues the country. Reform in Iraq necessitates more than just a change in policies; it requires a root-and-branch restructuring of the political, economic and constitutional foundations of the state.

This is a generational project that is beyond any one prime minister or political leader. It will require a fundamental rethinking of the Iraqi state and the ability to institute major reforms that threaten the interests of powerful vested interests. It will also require a level of political and social cohesion that Iraq has rarely, if ever, enjoyed in its modern history. The test for Abadi and other prophets of reform is therefore not whether they can transform Iraq in the course of one term in office, but whether they can establish the building blocks for long-term change, including reaching a common vision of governance and power-sharing, enshrined in a new constitution. Moving beyond communalism to more issue-based politics based on a new compact between the rulers and the ruled is an important first step in this direction. How the elections play out, and, more importantly, how the next government is formed and what its priorities are, will be an important indicator as to whether the current optimism is justified.

This is an abridged version of a paper given at a workshop on Iraq and its Regions: Baghdad–Provincial Relations After Mosul and Kirkuk, held at the LSE on 15 January 2018. See below for the full list of papers. As part of the Middle East Centre’s tenth anniversary celebrations in 2020, Raad revisited this piece – read his reflections here.

In this series:

- Introduction by Toby Dodge

- ‘Functioning Federalism’ in Iraq: A Critical Perspective by Ali Al-Mawlawi

- When People, Power and Politics Collide by Andrea Malouf

- Security in Iraq: From Cooperation to Confrontation by Michael Stephens

- The Popular Mobilisation Forces and the Balancing of Formal and Informal Power by Renad Mansour

- Peshmerga Unification in Jeopardy by Fazel Hawramy

- Baghdad and Erbil and the Path Forward: The Wisdom of Hitting the Reset Button by Akeel Abbas

- Assessing the post-referendum crisis between Erbil and Baghdad by Zeynep N. Kaya

2 Comments