by Mehmet Erman Erol

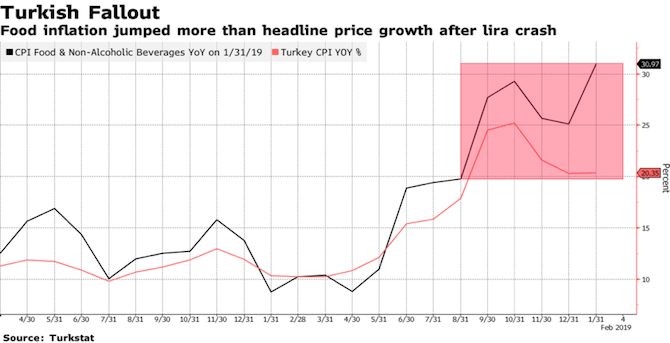

In President Erdoğan’s Turkey, almost no one and nothing can escape from the accusation of involvement in terrorism, if they act contrary to the will of the government. Against the backdrop of a radical rise in inflation following the 2018 currency crisis, and more importantly the recent sharp rise in food prices recently (see Figure 1 below), the latest accusation deployed by the government is of involvement in ‘food terrorism’. Clearly, President Erdoğan’s discourse reflects the tactic of shifting the blame away from his government and its policies to some obscure and sinister forces (either domestic or international) which seek to undermine Turkey, as discontentment has become widespread even among AKP (Erdoğan’s party) supporters in the run-up to the important local elections scheduled for 31 March 2019. It is worth remembering that economic conditions played a huge role in the 2009 local elections, where the AKP got its lowest ever vote share since 2002.

Despite being drastically reduced in the 2000s, high inflation was part and parcel of the Turkey’s political economy and the daily lives of its citizens for a long time. It even reached triple-digit figures in the crisis-ridden 1990s which led the government at that time to take measures to control inflation. The process, which started with the 1998 IMF Staff-Monitoring Programme, focused primarily on ‘disinflation’. However, more decisive steps were taken following the major crisis in 2001, and inflation targeting via the ‘independent’ (depoliticised) Central Bank became the primary objective of monetary policy. Although inflation targets could not generally be met, and this policy led to stagnant wages and persistent double-digit unemployment rate; the single-digit inflation rate was one of the sources of the AKP’s legitimacy, and the ever-increasing capital flows to the country in the 2000s.

However, this relative success was a fragile one. The economy remained dependent on imports, as the AKP government did not transform the Turkish economy structurally. Thanks to favourable global conditions and an overvalued exchange rate, this import-dependency did not create much of a problem for the inflation in the 2000s; in fact it helped to control it. As the global economic conditions had deteriorated for emerging markets such as Turkey in recent years, and also as a result of a number of other factors (for example the government’s interference in the Central Bank interest rate policy, the coup attempt, as well as the American Pastor Brunson case), the Turkish lira lost significant value in 2018 which had a direct impact on the inflation in an import-dependent economy, reaching 25% in September. Although the year end inflation rate decreased to 20.3%, it remained well above the Central Bank’s inflation target of 5% for 2018.

In order to quell inflationary tendencies and combat the currency crisis, as well as prove its credibility, the Central Bank of Turkey made a rather surprise move in September 2018 by raising the interest rate by 625 basis points, reaching 24%. Meanwhile, the Turkish economy grew by 1.6% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2018, slowing from an 5.3% expansion in the previous three-month period. Furthermore, on a seasonally adjusted quarterly basis, the economy contracted by 1.1% in the third quarter, leading to concerns that Turkey was on the brink of a stagflation. Little room for manoeuvre now remains for monetary policy, especially before the local elections. If the Central Bank increases the interest rate it would have a more contractionary effect on the economy; and if it loosens the ‘tight’ monetary policy, then this would exacerbate inflationary tendencies.

It was in this context that the AKP economic management introduced some unorthodox measures to reduce inflation and food prices. A government-led campaign of all-out fight against inflation urged businesses to reduce some prices by 10% in October, which was followed by some controversial tax cuts. The municipal police were also tasked with checking prices at grocery stores. Following this, the government started raiding onion warehouses to battle with the ‘hoarders’ who it believed to be responsible for a 51% increase in onion prices in November. Finally, as these coercive measures failed and the discontent among the voters increased, this month the government introduced municipality-led vegetable stalls in Istanbul and Ankara which sell products at heavily discounted prices (called tanzim satis).

This move clearly reflects a pre-election strategy and contain the discontentment among the electorate over food prices and economic conditions. Government representatives say that this action is planned to continue for two and a half months, which would have it ending just after the local elections on 31 March 2019. Although President Erdoğan declared that the ‘tanzim satis’ would be extended to other products as well, it is dubious that this strategy would successfully bring down the prices. Firstly, its impact stands to be limited. Furthermore, and more crucially, the AKP government has attempted to conceal the underlying economic policy reasons, such as rising overall production costs and more generally the failed agriculture policy and problems in agricultural production since the early 2000s; most of which the AKP is responsible for.

The AKP has always associated its rule with economic growth and prosperity, and consistently criticised earlier governments for failed and crisis-prone economic policies. The scenes of long queues of people waiting for hours to buy cheap but rationed fruit and vegetables clearly contradicts the party’s self-image and puts its electoral success at risk. However, one thing President Erdoğan has excelled at over the last 16 years is shifting the blame away from his government’s policies and successfully externalising the responsibility for its failures. Now he casts these developments as the conspiracy of foreign powers and domestic profiteers; representing himself as the saviour of the poor, fighting against forces who conspire to create miserable conditions for his people. This strategy might once again prove successful, considering the lack of a strong and effective opposition with an alternative progressive economic vision.

Mehmet Erman Erol is a Lecturer in Politics at Ordu University, Turkey. He received an MA in IPE (2011) and a PhD in Politics (2016), both from the University of York, UK. His research focuses on the political economy of Turkey, especially the AKP era; and he teaches IPE, Politics, and Turkish & MENA Political Economy. He has been published in the Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, Review of Radical Political Economics and Political Studies Review, with op-eds in SPERI (Sheffield University), Research Turkey and the Socialist Project. He tweets at @mehmetermanerol

Mehmet Erman Erol is a Lecturer in Politics at Ordu University, Turkey. He received an MA in IPE (2011) and a PhD in Politics (2016), both from the University of York, UK. His research focuses on the political economy of Turkey, especially the AKP era; and he teaches IPE, Politics, and Turkish & MENA Political Economy. He has been published in the Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies, Review of Radical Political Economics and Political Studies Review, with op-eds in SPERI (Sheffield University), Research Turkey and the Socialist Project. He tweets at @mehmetermanerol

V good article if you could send more on price control in Turkey