by Desirée Custers

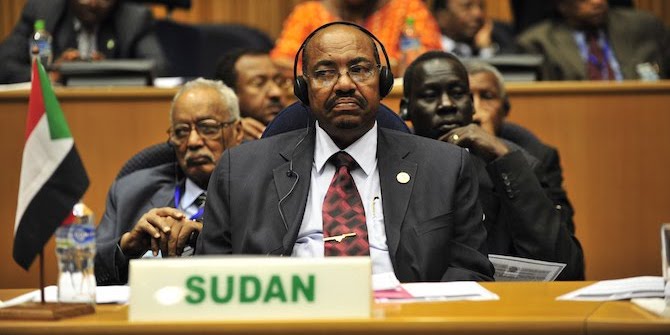

The international attention given to Sudan’s normalisation with Israel has shown the country’s importance as a geostrategic site subject to regional rivalries in the Horn of Africa. But increased regional pressure on Sudan is endangering its transition towards an inclusive, civilian government following the peaceful popular revolution that led to the ousting of long-ruling president Omar Al-Bashir on 11 April 2019. This article will describe how regional interference in Sudan could destabilise the transitional process, with a specific focus on the rivalry between the ‘Arab Troika’ and the Qatar-Turkey alliance.

The Sudanese Revolution and Political Shifts

Following the ousting of Bashir in 2019, military and civilian leaders signed a power-sharing agreement which initiated a transition towards a democratic government, under the guidance of Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok and Chairman of Sudan’s ruling Transitional Military Council, Lieutenant-General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan. This transition signified a shift in Sudan’s foreign policy.

During Bashir’s 30-year rule, Sudan enjoyed close relationships with Turkey and Qatar. This included a deal between Turkey and Sudan that gave Ankara control over the Suakin Island in the Red Sea, a deal which has since been suspended. However, this did not prevent Bashir from moving closer to the UAE and Saudi Arabia from 2014 onwards, in the hopes of bettering relations with the US and securing financial gains from the Gulf. When the Qatar diplomatic crisis erupted in 2017, Bashir decided to remain neutral, a move that accelerated Sudan’s eventual economic collapse.

Geostrategic Interests

When the revolution erupted in 2018, the Arab Troika (the UAE, Egypt and Saudi Arabia) saw its chance to gain a stronger foothold in Sudan while minimising the influence of its rivals Turkey and Qatar. It supported the demonstrators, but simultaneously sought to strengthen the position of generals who could push for their foreign policy interests and solidify their influence. The UAE and Saudi Arabia specifically supported Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (otherwise known as ‘Hemedti’).

The rivalry between the two alliances is driven by geostrategic economic and military interests. Important are the Sudanese Red Sea coastline, which includes sizeable ports and oil-export facilities, and agricultural land. Companies from Saudi Arabia and UAE own much of the leased land in Sudan, which they use to produce food crops, alfalfa and biofuels, and which has added up to more than all of Sudan’s domestic agribusiness investors combined. Militarily, both the UAE and Turkey have used Sudan as a springboard for their war efforts in Libya.

Normalisation with Israel

Part of the UAE’s strategy has been to include Sudan in its normalisation policy with Israel. The US, in its mob-like tactics, has linked normalisation with Sudan’s removal from the State Sponsor of Terrorism (SST) list. The first step to this was taken on 19 October, when the transitional government agreed to pay a sum of $335 million to American victims of Sudan’s past terrorist acts. This was followed on 23 October with the announcement that Sudan will move to normalise relations with Israel.

Although normalisation could lead to increased economic opportunities, it also strengthens military actors and former Bashir regime figures in government. Herein lies the danger of increased tensions within the transitional government, as well as overall mistrust in the transitional process by protestors who had demanded a civilian government. The government is concerned that frustration among the Sudanese could lead to renewed protests and its eventual collapse.

Political Islam

Sudan after the revolution shows a clear break with a radical form of Islamic rule associated with the corruption and suppression of Bashir. However, the marginalisation of Islamist movements without a distinction being made between those who supported the demonstrations and those who were part of the Bashir government, has led to frustration among Islamists and their supporters. Islamists have (though not exclusively) used normalisation as a rallying cry in their attempts to topple the government.

Although the influence of Islamists is limited in post-Bashir Sudan, Turkey and Qatar, both long considered backers of Islamist movements (and opposed to the Arab Troika) could gain more ground if support for the transitional government decreases. After the ousting of Bashir, Turkey, in an attempt to regain some of the influence lost, met with Islamist loyalists and offered refuge to some members of the former government. The topic of political Islam has even reported to be a factor in the distribution of humanitarian aid during the massive floods, as Qatar and Turkey distributed to Islamic organisations in the peripheries that support their political agendas.

Conflict in the Periphery

The regional rivalry between the Arab Troika on one side, and Turkey and Qatar on the other, also plays into Sudan’s already existing social grievances and territorial issues. In eastern Sudan, where protests erupted following opposition to the peace-deal signed between the government and eastern rebels, tribal clashes occurred in Kassala between the Beni Amer and Beji tribe, leading to several fatalities. While these clashes were caused by disagreement over the appointed governor, who has since been dismissed, it is also reported to be intensified by fears of intervention by both the Turkish alliance and Arab Gulf backers of the peace deal. Recently, the transitional authority has started pointing to the role of foreign interference in the eastern region bordering the Red Sea.

Conclusion

The 2018 Sudanese revolution initiated a period of redefining Sudan’s social and political identity. The process has unfortunately not been free from external interference. This article has described only one of the regional power dynamics at play, showing how external rivalries have intensified instability in Sudan – and vice-versa – and are therefore undermining the transition towards a democratic government.

Sudan faces pressing economic conditions, tensions between the military and civilian sides of the government, and more recently the threat of a humanitarian crisis in eastern Sudan following conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region. Nevertheless, removing Sudan from the SST list is an important step towards Sudan’s reintegration into the global arena. Hopefully it can lead to further international support for Sudan’s transitional process that does not compromise the demands of the revolution.

The writer didn’t elaborate in the role that played by the youth the real players in the political scene. They made the change by taking the lead of the revolution but the force of the freedom and change pushed them away and became the civilian part of the government. The writer also missed to analyses the real power of the Islamist in the political scene, I can say clearly that the Islamist neither the communist, leftists, and umma parties has any political supports or popularity. In last, Sudan’s normal position is with USA ans it’s allies Int the region.

Dear Habib,

Thank you for reading the article.

As you write, I have indeed not elaborated on the important role played by the youth and by women – though it is their voice that I refer to when I write about the peaceful popular revolution and the demands of the revolution. My message is that they should not be overshadowed, which sadly is happening.

I alluded to the fact that Islamist parties have limited support, as you write no support. But indicate that this could possibly change.

Thank you for your feedback.

Desiree