by Isaac Avery

A decade on from the self-immolation of Mohamed Bouazizi, the term ‘Arab Spring’ remains synonymous with the violent and non-violent demonstrations, protests, coups and civil wars that took place in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region between 2010–12. However, the expression remains highly problematic for a number of reasons.

Firstly, the term ‘Arab Spring’ was used by Western commentators but not by those involved in protests, who instead demanded karama (dignity) and thawra (revolution) and used expressions like al-marar al-Arabi (the Arab bitterness). Maytha Alhassen points out that ‘the irony of the Western invention of the “Arab Spring” is that regardless of citizenry remonstrations for “self-determination”, we still continue to see the Arab region in our eyes and not through theirs’.

This labelling typifies Edward Said’s third meaning of Orientalism: ‘a Western style for dominating, restricting, and having authority over the Orient’. This sense of superiority has led to ignorance when it comes to other parts of the world. The saying goes that history is written by the victors, however, it is more accurate to say that history has largely been written by the West. Outlooks on the world have been Western-centric, with the rest of the world examined in relation to the West. Indeed, the Middle East region was named according to its geographical position in relation to the West.

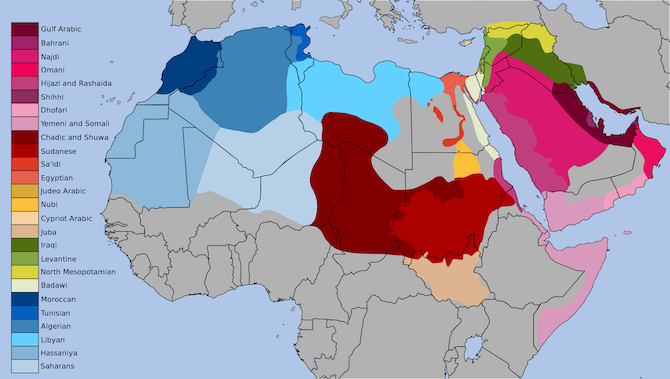

The second problem with the term is that the grouping of the diverse MENA region into the homogenising term ‘Arab’ ignores the region’s cultural idiosyncrasies. The term grossly oversimplifies the complex and varied nature of the Middle East and assumes people of the region are culturally and ethnically similar; with a shared history, culture, religion and language. This is clearly not the case, as the map below demonstrates.

It also suggests that there was a single unifying wave of similar popular protest, when in reality the ‘Arab Spring’ was not a unitary process and had dramatically different outcomes in different countries.

Thirdly, the word ‘Spring’, is problematic as it denotes an expectation that events would follow the example set by the West. It is a reference to the democratic European revolutions of 1848, often known as ‘Spring of Nations’, ‘People’s Spring’ or ‘Springtime of the Peoples’. This led to an expectation that the MENA would peacefully transition from autocracy to democracy. Similar comparisons were also made in 2011, with Barack Obama citing Poland as a model for Arab nations to follow. However, apart from fact that no two revolutions are the same, this point ignored the fact that the fall of communism in 1989 saw the breakdown of a single outdated political system.

The season is also associated with the return of life and light following the dark slumber of winter. It suggests that the people of the MENA, who had for years been subject to brutal authoritarian rule, one day realised their situation and took to the streets. This is not only an offensive portrayal of the people of the region but also inaccurate as revolutions do not happen overnight.

Finally, from a semantic perspective the term is extremely uninformative. Without prior knowledge of events, ‘Arab Spring’ could have a whole host of meanings. The term was first used by commentators describing the ‘short-lived flowering of Middle Eastern democracy movements in 2005’. It is now ubiquitous with the events of 2010 onwards – evident in the term’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary – however, from a literal standpoint, the phrase could refer to either of these periods.

Moreover, it is not clear if the ‘Arab Spring’ is one event or multiple, a small uprising or a revolution. While events in Tunisia or Egypt are often individually referred to as revolutions, those in Syria are usually labelled a civil war. The notion of what constitutes an uprising compared with a protest or a revolt is often confusing, however, in terms of labelling, the 2010 ‘Thai political protests’ are much more descriptive than the ‘Arab Spring’.

The term ‘Arab Spring’ thus proves to be simply a catchphrase with no real substance. It raised expectations of a peaceful democratic transition of power that meant the initial optimistic coverage of the ‘Arab Spring’ period gave way to numerous damning accounts. Yet in many countries the demands for political freedom forced a change of government for the first time in decades. The events of 2010–12, which has been described as the ‘biggest transformation of the region since decolonisation’, also forced the West to recognise that the MENA region was not docile or dormant but vibrant and motivated.

This raises the question as to why we continue to use a term that is loaded with Western bias and does not reflect the opinions and terminology of those involved. As no Western term would appropriately address all the complexities, we should consider adopting terms like karama, thawra, and al-marar al-Arabi that were used by those who were involved in the events of 2010–12, rather than imposing our own.

While your arguments are generally logical, I think they miss out on a glaringly obvious truth. Western mirror imaging through the use of a term like “the Arab Spring” is not necessarily related to the quest for a clear-eyed perception of social dynamics in the MENA. But it is very plainly about a cloaked Western self-dialogue between conservative and liberal/globalist and nationalist influences. Your use of Said and the tired complaints about Orientalism suggests the delegitimization of Western soul-searching because it is projected upon and through the West’s witnessing external experiences as Westerners. Just because there is an uncomfortable history that has led many Westerners into feeling guilt-ridden does not mean that the terminology used and the perceptions privileged are principally about impositions foisted on our MENA neighbors.

Your article is very insightful, and I like how you recommend alternative terms that could be used in Arabic. However, the term “Arab Spring” seems to be embedded in English vernacular, and is used on English-speaking news. The Western world has become attached to this concept and will likely keep talking about it, even if it is uninformed to do so as you so elegantly point out. What alternative terms would you recommend we should use in English?