by Maximilian Hörtnagl

One of the raisons d’être of the ICC, as laid out in the preamble of the Rome Statute, is to prevent future crimes within its jurisdiction by putting an end to impunity. Atrocities, namely genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes and aggression, are to be effectively stigmatised through prosecuting the perpetrators. The problem here is that the prevention of crime, or ‘deterrence’ in criminal justice parlance, is difficult to measure, expectations towards the court are often too high and the evidence from existing empirical studies remains inconclusive.

The aim of my MSc dissertation at the LSE was to better understand if and under which conditions the ICC can deter atrocities. In theory, the court should be able to deter rational would-be perpetrators because of the threat of prosecution and the pariah status that comes with an ICC investigation. Even desperate, erratic or psychotic leaders engage in some form of rational cost-benefit analysis when committing violence, Payam Akhavan reminds us. If the threat of prosecution for their actions is real, leaders may refrain from using violence as a tool to stay in power.

But without a global police force to enforce its arrest warrants, the ICC relies on support from its 123 state parties and the UN Security Council to be a credible threat. Hence, I argued further that the ICC’s deterrence potential is influenced by the level of international support from states, and especially the five permanent members of the Security Council, at different stages of the investigation.

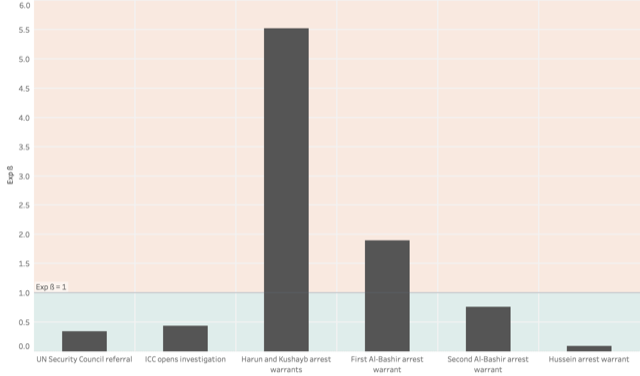

To test those assumptions, I focused on the ICC’s investigation in Darfur, Sudan – a region that experienced a bloody ethnic conflict and was the subject of the first Security Council referral to the ICC. I studied the effect of six concrete ‘ICC actions’ between 2005 and 2012 on reported daily civilian fatalities in Darfur. The regression model also uses news coverage and conflict intensity as controls.

The results are summarised below where the height of each bar denotes the expected effect of each ICC action on civilian fatalities in the 90 days following it. Low bars indicate a positive deterrence effect, i.e. an observed reduction in civilian fatalities. High bars (above exp ß = 1) indicate an increase in civilian deaths after the ICC action.

The results above indicate that the ICC had a clear deterrent effect at the beginning of the Darfur conflict. For instance, the UN Security Council referral is associated with a three-fold decrease in civilian fatalities. My qualitative research demonstrates that this can be, at least partly, attributed to the international community’s early willingness to prosecute the Al-Bashir government. However, arrest warrants appear to have escalated government violence against civilians in Darfur. The first arrest warrant against Harun and Kushayb is associated with a more than five-fold increase in civilian fatalities. Notably, Sudan had been uncooperative with the arrest warrants against its own government officials. Furthermore China, an ally of Al-Bashir, was prepared to veto any intervention by resolution in the Security Council. In later stages, the ICC appears to have again had a strong effect in reducing violence against civilians.

What can academics, policymakers and the ICC prosecutor take away from this analysis? Firstly, that more empirical studies are needed to confirm whether and how deterrence works in specific ICC situations. How do deterrence effects differ, for example, in situations which are brought to the court through a self-referral by a state party? Or by the ICC prosecutor herself via her proprio motu powers?

Secondly, the ICC prosecutor needs to issue arrest warrants carefully and strategically because they can lead to an increase in violence against civilians. Political solutions need to accompany legal arrest warrants if they are to be executed successfully.

Finally, and somewhat unsurprisingly given the architecture of the Rome Statute, the ICC relies on continued support from states to slowly close the impunity gap. Ending impunity for all perpetrators remains elusive given the court’s politicised environment, but a well-backed International Criminal Court has the potential to save many lives.