by Emma Söderqvist

The following is an abridged report by Salam for Democracy and Human Rights on cyber-authoritarianism and the digital sphere in Bahrain, written by Emma Söderqvist and edited by Andrew McIntosh. The full version is available at https://salam-dhr.org/?lang=en

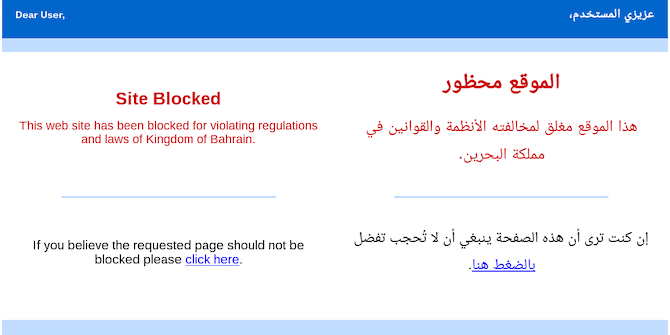

While Bahrain has the second highest internet penetration rate in the Middle East at 98.6%, this is matched by attempts from the government to curtail the digital sphere, reflected in Bahrain’s Freedom House score of 2.5/10 in 2017 for state control over the internet. In 2019 Bahrain’s Freedom on the Net was rated at a mere 29/100, recording the banning of independent media and suppression of social media activity, referencing arbitrary or unlawful interference with privacy; restrictions on freedom of expression, the press, and the internet, including censorship, site blocking, and criminal libel.

Since 2009, the Bahraini Telecommunications Regulatory Augthority has ordered all telecommunications companies to record customers’ phone calls, emails, and website visits for a period of up to three years. Additionally, the country has made extensive acquisition of spyware over the last 10 years, particularly for use against dissidents. In October 2018 Bahrain purchased espionage and intelligence-gathering software from private companies, including a system from the Israeli company, Verint, used for collecting information from social networks. It’s also alleged Bahrain is using the Israeli spyware, Pegasus, which infiltrates phones through an exploit link, and subsequently grants access to complex mobile phone operations and private information. The government also purchased almost USD $500,000 worth of British surveillance equipment between 2015 and 2017.

Ranking 149 out of 167 countries in the Democracy Index, with a score of 2.55/10, repression in Bahrain accelerated after the 2011 uprisings when thousands of pro-democracy protestors took to the streets to demand socio-political reforms. The government crackdown continues today, with constant infringement upon human rights increasingly in the online sphere. Most internet-service providers in Bahrain are dependent on leased access to the network, Batelco, the dominant, partly state-owned telecommunications firm. The launch of the Bahrain National Broadband Network in 2019 gave the government sole control of the national fiber-optic broadband network. This monopoly affords the ability to exert control, even completely shutting down the entire country’s broadband network – as happened most recently in Belarus and Ethiopia.

In Bahrain, these actions are legitimised through broad legislation. The Terrorist Act allows the prosecution of organisations, individuals and political parties which openly express disagreement with the government; including non-violent acts that ‘disrupt public order’ and threaten ‘the Kingdom’s safety and security’.

A lack of legislation specific to the digital sphere, along with deliberately vague wording, enables censorship and abuse online. Lack of accountability and attention paid to breaches of digital human rights in Bahrain may be due to the business and diplomatic interests of international actors, trumping any human rights abuses in the digital sphere, where they are often overlooked.

Officially, the constitution states that ‘freedom of the press, printing and publishing is guaranteed under the rules and conditions laid down by law’. However, authorities have banned all independent media and nationalised the rest, with the Ministry of Information blocking websites containing content critical of the government using the Telecommunications Regulation Authority. This followed the implementation of the 2002 Press Law, which allowed censorship of online media to protect intellectual property. The Information Affairs Authority has blocked the website of the opposition party, Al-Wefaq, over rumours it planned to start an audio-visual service. It also banned audio and video reports on Al-Wasat, prior to the newspaper’s forced closure in 2017.

Countries worldwide are utilising the digital sphere to help curb the spread of COVID-19. As tracking systems proliferate in attempts to locate virus hotspots, there may be implications for citizens’ privacy. Bahrain was praised by the WHO in 2020 for its rapid implementation of health strategies, with the Information and eGovernment Authority launching the BeAware phone application in order to track and identify coronavirus cases. Soon after, the Authority also released an electronic wristband to keep track of active cases. Affected wearers of the bracelet must be connected to the app at all times via Bluetooth, with GPS enabled to track movement. An alert is sent to a Ministry of Health monitoring station if the wristband-wearer moves more than 15 metres from their phone. These tools likely pre-date the pandemic.

Cyber protection laws have been drafted, notably in the EU, since the introduction of the Cyberprotection Act in 2005, followed by GDPR in 2016. Nevertheless, they fail to include the breadth and extent of online human rights breaches. Since the online world has become a important realm of human life, it is crucial that emphasis is placed on enshrining the digital sphere in human rights legislation internationally, and that the Bahraini government is held accountable for any breaches.

The immense global power and influence amassed by this sphere has, as with other societal sectors, subjected it to rights and regulations. However, the growth of the online world is outpacing legislative development, leaving it ripe for abuse, particularly in authoritarian regimes such as Bahrain.

Our digital existence will continue to gain importance and shape more aspects of our lives. In the Bahraini context, it is of utmost urgency to ensure a halt of the weaponisation of the digital sphere as seen this far; which only becomes more dangerous, intrusive and difficult to undo the longer it is left unchecked. Cyber protection must be included in discussions of human rights, and be regarded with the same level of seriousness as any other human rights violations.