by Ahmed Tabaqchali

*In Roman times the Ides of March was mostly notable as a deadline for settling debts.

On the eve of the Ides of March, Iraq’s Council of Ministers (CoM) submitted its 2023 budget proposal to the Council of Representatives (CoR) for review. The budget proposal reflects the political priorities of the new administration, and crucially those of the parties within the State Administration Coalition (SAC), the drivers of the government’s formation in October 2022 following a year of deadlock fraught with political conflict.

Irrespective of the budget’s unprecedented spending plans at 199 trillion Iraqi Dinars (IQD), or $153 billion, it essentially perpetuates the structural imbalances between current and investment expenditures that characterised prior budgets, especially following periods of high oil prices. However, it differs in three key aspects: the first is that it was made in consultation with the SAC, with the hope that it would be passed by the CoR into law with minimum changes; the second is that it’s proposed for three years instead of the usual one, to provide the government with political stability over its term in office; and the third is that it contains a framework to address the dispute between the federal authorities and the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) over oil exports in a way that would both satisfy the February 2022 ruling of the Federal Supreme Court (FSC), and to provide for the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)’s share of the budget.

This piece reviews the main thrust of the proposal as it applies for federal Iraq excluding the KRI, with planned upcoming pieces to review the budget’s other aspects such as the implications for the KRI, government debt, the CoR’s amendments, and the final budget once it passes into law.

Overview

The budget proposal calls for total spending of IQD 199 trillion, made up of current expenditures of IQD 149.6 trillion and investment spending of IQD 49.5 trillion. Revenues are projected at IQD 134.6 trillion, made up of oil revenues of IQD 117.3 trillion based on exporting 3,500,000 barrels per day (bpd) at an average price of $70 per barrel (/bbl), and non-oil revenues of IQD 17.3 trillion. The resultant deficit of IQD 64.5 trillion would be financed by IQD 23 trillion from the Ministry of Finance’s (MoF) account at the Central Bank of Iraq (CBI), IQD 10 trillion from ongoing foreign financing of investment projects, which therefore calls for new domestic borrowing of IQD 31.5 trillion (Table 1).

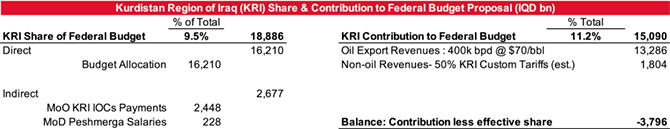

The budget proposal includes a budget allocation to the KRI of IQD 16.2 trillion, representing 12.7% of total spending excluding sovereign expenses, or an effective 8.1% of total spending. While its contributions are IQD 13.3 trillion in oil export revenues based on exports of 400,000 bpd at an average price of $70/bbl, and 50% of custom tariffs, amounting to 11.2% of total revenues.

However, the KRI’s effective share is larger by IQD 2.7 trillion, or 16.5%, as the federal Ministry of Oil (MoO) would assume some of the payments for the International Oil Companies (IOCs) operating in the KRI, while the federal Ministry of Defence (MoD) would assume some of the Peshmerga’s salaries (Table 2).

Expenditures

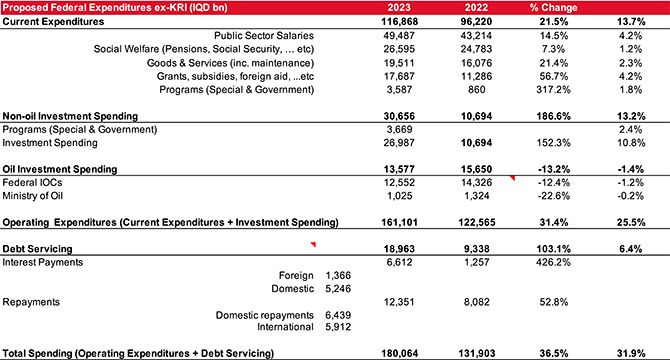

Proposed ex-KRI expenditures for 2023 are compared against actual spending in 2022, which was a combination of one-twelfth of 2021 appropriations – the one-twelfth rule as no budget was not passed for 2022 – and the Emergency Food Bill in June 2022, which was effectively a supplementary budget (Table 3).

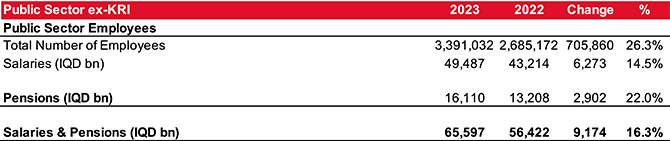

Current expenditures are projected at 73% of operating expenditures, while non-oil investment spending is projected at 19%, or over a quarter of current expenditures. Public sector salaries and pensions are projected to count 41% of operating expenditures (Table 4).

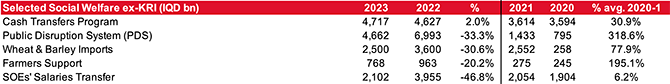

Projected social welfare spending show meaningful declines, but these are due to large allocations made in the food security bill. As such comparison should be against budgeted allocations for 2021-2020, which show significant increases, with the combined figure of IQD 14.8 trillion accounting for 9% of operating expenditures (Table 5).

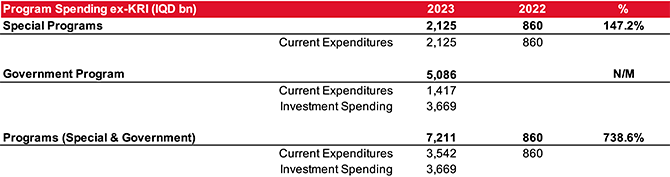

The new administration’s priorities are expressed through its program made up of current and investment spending of IQD 5.1 trillion, accounting for 3% of operating expenditures, which increases to IQD 7.2 trillion, or 5% of operating expenditures, with the addition of ongoing special programs (Table 6).

With debt, by the end of 2022, reaching IQD 94.9 trillion (IQD 70.5/24.4 trillion domestic/external), its servicing at IQD 19 trillion is projected to double, accounting for 11% of total expenditures, versus 7% for the prior year.

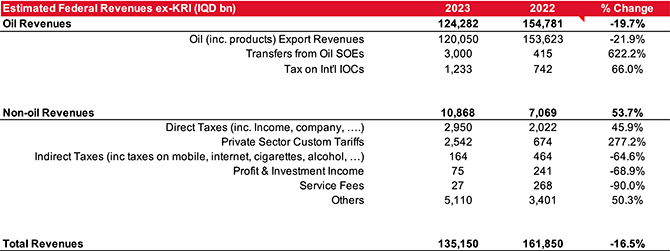

Revenues

The budget’s oil revenues forecast is based on assumptions for oil exports and prices for 2023, however, the lag between invoicing and payments for oil exports mean that in practise the MoF recognises oil revenues with about a three-month lag. As such, the budget’s assumptions do not account for three months of export revenues that were made in the prior year, and the budget’s timing means that a further three months of export revenues were already made in 2023 but yet to be received.

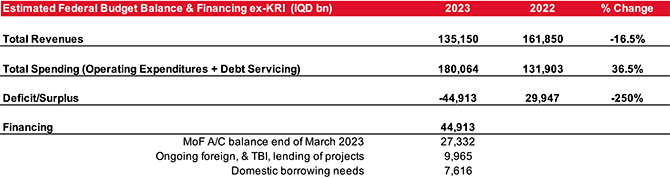

Therefore, projected oil revenues for the first half of 2023 are almost certain, and are estimated based on the IQD 66.5 trillion oil export sales from October 2022–March 2023, averaging 3,300,000 bpd and a price of $78/bbl – both higher than the budget’s assumptions (Tables 1 & 7). Moreover, April’s export sales were reported following the release of the budget proposal at IQD 10.1 trillion, averaging 3,300,000 bpd and a price of $79 – again both higher than the budget’s assumptions. Thus, assuming 3,100,000 bpd of oil exports, and current (as of publication date) implied market prices for Iraqi oil of USD 71/bbl for May–September 2023, would translate to oil revenues for 2023 ending up IQD 16.1 trillion higher than the budget’s projections. These assumptions, and the budget’s assumptions for oil-related revenues and non-oil revenues imply total revenues of IQD 135.2 trillion (Table 7).

Deficit

The projected deficit would be financed by MoF’s account balances, existing ongoing foreign lending, and IQD 7.6 trillion in new domestic borrowing (Table 8).

The historic low execution rates for investment spending and the likely budget’s passage by May, render it highly unlikely that more than half of non-oil investments will be spent. As such, this could cut the deficit to IQD 29.6 trillion, removing the need for new domestic borrowing, and leaving MoF with about IQD 7.7 trillion in cash balances that would either be used for the following year or would provide a cushion should oil revenues for the next five months be lower than projected.

The Budget’s Second and Third Years

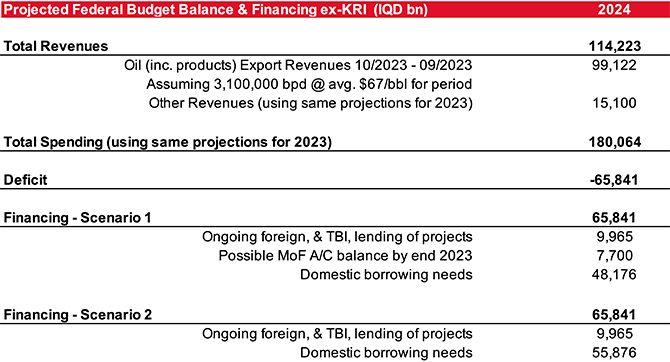

High oil prices in 2022, and the medium-term outlook for elevated oil prices, albeit lower than 2022, provides the government with the flexibility to pursue its spending plans for 2023. However, these dynamics would change even when assuming continued elevated oil prices in 2024, again lower than in 2023 (Table 9).

The projected deficit of IQD 65.8 trillion for 2024 implies domestic borrowing needs of IQD 48.2–55.9 trillion, depending on investment spending execution rates in 2023. Should these rates be repeated in 2024, the deficit decreases to IQD 50.5 trillion, implying domestic borrowing needs between IQD 32.8-40.6 trillion

This scenario would be repeated in 2025, should oil prices be the same as assumed for 2024, but further domestic borrowing means that the stock of domestic debt could be larger by 70-80% by end of 2024 than at the end of 2022; and by a total of 140-160% by end of 2025 than at the end of 2022 – depending on actual deficits in 2024 and 2025, and on investment spending execution rates in these two years.

The budget’s sensitivity to oil prices is such that every $1/bbl decline in annual average Iraqi oil prices translates to a revenue decline of IQD 1.5 trillion (assuming oil exports as in Table 9, and current $/IQD exchange rate) and thus increasing domestic borrowing needs. On the other hand, higher oil prices would change the picture for the better, but would not change the trajectory for domestic debt to increasingly augment oil revenues – and with that debt servicing, in on successive years, accounting for larger and larger portions of total spending. This, over time, leads to a crowding out of other budget spending and less flexibility for future budget planning

Conclusion

The oversized role of the government in the economy means its expenditures – public sector payroll, social welfare, subsidies, good and services, and even underspent investment spending – results in an efficient and direct transmission mechanism of oil revenues into the real economy. As such, the budget’s proposed expenditures, even with a small fraction of its investment spending plans, will result in significant liquidity injections into the non-oil economy over the next 18-24 months. These will fuel economic growth, and in the process increase the ruling elite’s public legitimacy and will likely stave off any social unrest – at least for the medium-term.

However, seeking legitimacy from an increasingly alienated public comes with policies that increase leverage to volatile oil prices, and with that increase the vulnerability to external shocks as in 2020. Yet it’s the trajectory of increased domestic debt and its increasing servicing needs, not volatile oil prices, that call out ‘beware the Ides of March’.

[To read more on this and everything Middle East, the LSE Middle East Centre Library is now open for browsing and borrowing for LSE students and staff. For more information, please visit the MEC Library page.]