Fathima Rena Abdulla & Afrah Abdul Gafoor

As Erdogan’s presidential rule extends to its third decade in Turkey, it has renewed the debates surrounding the role of religion in voting behaviour. In this piece, we analyse the extent of influence of religion as a political instrument in Turkey while situating it in the broader Middle Eastern context.

Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi’s (AKP) success in its electoral strategy is generally attributed to capitalisation on the secular-religious divide in Turkey, ensuing its history of resentment with the authoritarian secular rule established by Ataturk. Scholars including Ahmet Ozturk, M. Hakan Yavuz, Nil Mutluer and others have largely attributed Erdogan’s political success in Turkey to AKP’s systematic use of Islam as a political tool to gain what is known as the ‘Islamic trust advantage’. But, on the contrary, empirical studies done in this area might lead us to a different conclusion. T. Piketty, L. Assouad, A. Gethin, and J. Uraz’s empirical analysis of Turkey’s political cleavages reveals that increased support for Islamic parties is not necessarily linked to heightened religiosity among voters. Additionally, since 1991, religious voters are in general more likely to vote for right wing parties by 25 to 35 percentage points and it has by and large remained in this range not revealing any significant upgrade during Erdogan’s reign. Hence, the tendency to overemphasise the role of religion in AKP’s electoral wins is problematic because neither does it provide an accurate representation of Erdogan’s political appeal, nor does it correctly describe AKP’s political strategy. We suggest that the AKP’s ascendancy can be attributed to a complex interplay of socio-economic factors, intra-elite conflicts, and the redefinition of Islamic identity in alignment with economic interests instead of religiosity of voters alone.

One cannot completely rely on the fact that Islamisation of Turkey is being spread at present through Recep’s reign, as the Islamist idea was always present in Turkish society, but was alienated or rather contained by the Western ideologies. Erdogan’s rigor lied in his strength to interpret and bring shape to the average Anatolian Turk’s concepts, who were those people who lived away from the big bustling cities and who cared more about their day to day aspects. Erdogan won the hearts of this Anatolian Middle Class, by positioning himself as the torchbearer of a conservative democracy rooted in cultural values, while simultaneously embracing a more liberal approach to economic matters. This backing has been solidified through the implementation of housing policies, clientelist practices, and public procurement contracts that benefit this particular demographic. Moreover, the party’s emphasis on fiscal discipline, low inflation, and policies favouring small and medium enterprises resonates with both economically disadvantaged workers and business owners. So, the AKP’s initial success can be attributed to multiple factors outside of religion including its ability to appeal to a wide array of groups, including low-income individuals, the pious, the burgeoning liberal bourgeoisie, and impoverished urban workers.

The political environment in the MENA region is well known for its authoritarian governments, instability and corruption. A lot of times, like the case in Turkey, in popular media, the root of this authoritarian tendency is falsely traced to religiosity of the population. But a closer look at the history of the region will reveal that this authoritarian tendency is more closely linked to political culture rather than religiosity of the population. This is highlighted by the numerous autocratic secular governments that have and continue to come in and out of power in the region. The greatest example of this has to be Turkey itself with the secular bureaucratic military influenced rule it had to undergo from 1920 to 2000 with laws that advocated for complete exclusion of religion from public life. Another relevant example is the case of Egypt whose Government has alternated between secular autocracies and Islamist political parties making democratic promises. The rise and success of Ennahda during the Arab Spring in Tunisia greatly resembles the rise of AKP. However, even there, like Turkey, the government has plunged into an autocracy after Kais Saed, the elected president declared himself as the chief executive and sacked the Prime Minister in 2021. While it becomes tempting to attribute the authoritarian drift to religion, evidence reveals it is other factors such as class and perceptions of nationalism that influence the political dynamic.

This is especially true for Turkey where nationalist sentiments using a narrative of reinstating Ottoman lost glory is often used as a justification for trampling on civil and political liberties. Erdogan, running with this understanding of the average Turk, seems like he is on the run to be the descending Ottoman Prince – restoring his nation’s “glory” with Hagia Sophia and committing atrocities like the one in Gezi Park – while pretending to achieve his purpose, he distracts his supporters from Turkey’s failing economy. This is why he acts as Turkey’s reigning autocrat, hiding behind a tainted judiciary and antiquated rules that equate criticism with insult rather than winning fights on their merits. Following the failed coup attempt in 2016 which incentivised the authoritarian drift, a constitutional referendum in 2017 enshrined the transition to a robust presidential system. Subsequently, it’s not too hard to understand why he would oppress Turkey’s ten million Alevis, and rather than debate his own Muslim brotherhood inspired views with the followers of his former Comrade Fethullah Gulen a man whose Sufi-inspired interpretations have deep roots in Anatolia, he labels them terrorists and imprisons them. In conclusion, it is Erdogan’s attempt at “gatekeeping” nationalism which has won. All of this means that, despite the fact that Erdogan’s political Islam roots cannot be disregarded and remain appealing to domestic conservatives, Turkish nationalism is arguably the stronger ideology within the Turkish administration and will probably remain so in the future.

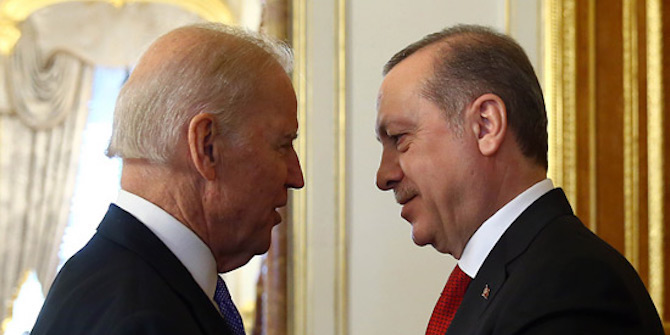

But for now, speaking of authoritarianism, while voters did have a choice between legitimate political alternatives, Erdogan’s near-total control of broadcast media and his extensive appearances on television juxtaposed with his opponents’ reliance on YouTube and social media platforms tilted the scales in his favour. He has already managed to quit the Istanbul Convention on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence, being the first country in the Council of Europe to do so – so his capabilities in achieving his faulty aspirations are impeccable and not to be questioned. During his inaugural address at the presidential palace, Erdogan articulated his dissatisfaction with the existing constitution, deeming it a by-product of the 1980 coup, and advocated for its replacement with a new constitution that promotes “libertarian principles, civil liberties, and inclusivity” to fortify the democratic system. Ironically enough, after speaking of inclusivity, he went on to speak out against what he called “LGBT forces”, he claimed that they were a threat to the sacred institution of family and he will “strangle anyone who dares to touch it”. Inevitably drifting towards more authoritarianism, Turkey’s elections are slowly becoming a continuous consolidation of conservative power rather than a mechanism for change and in the presence of chauvinistic nationalism, religion cannot take the full blame.

[To read more on this and everything Middle East, the LSE Middle East Centre Library is now open for browsing and borrowing for LSE students and staff. For more information, please visit the MEC Library page.]

1 Comments