Last week, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) revised its stance on screen time. Sonia Livingstone takes a closer look at the new recommendations and their evidence base. She argues that while the new guidelines fit better with the current circumstances of family lives, the AAP faces a dilemma: there isn’t yet a robust body of research on the effects of digital media on children, yet parents want guidance now. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

Last week, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) revised its stance on screen time. Sonia Livingstone takes a closer look at the new recommendations and their evidence base. She argues that while the new guidelines fit better with the current circumstances of family lives, the AAP faces a dilemma: there isn’t yet a robust body of research on the effects of digital media on children, yet parents want guidance now. Sonia is Professor of Social Psychology at LSE’s Department of Media and Communications and has more than 25 years of experience in media research with a particular focus on children and young people. She is the lead investigator of the Parenting for a Digital Future research project.

From the days when television was the main screen at home, well before today’s influx of tablets, smart phones, games consoles and laptops, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) formulated its famous 2×2 screen time recommendations for families: no screen time for children younger than 2, no more than 2 hours per day for older children.

Now the AAP has revised its recommendations (21/10/16), given that the media environment in homes is changing fast, as is the evidence about its possible impacts. The new recommendations include:

- A personalised Family Media Plan, including rules for children and their parents, and designated ‘media free’ times – the AAP provides an interactive online tool to help create this.

- Rather than policing or controlling or monitoring their children’s media use, parents should think of themselves as their child’s ‘media mentor’.

- Infants and toddlers should be ‘unplugged,’ though even infants are now allowed to Skype granny, and from 18 months old, high quality television content is also OK as long as a parent watches with them.

- For 2-5 year olds, screen time should be less than one hour per day, again with parents watching alongside to interpret and discuss what they’re watching.

- Children from 6+ need that media use plan, with limits to ensure screen time doesn’t displace sleeping, playing, conversation and physical activities.

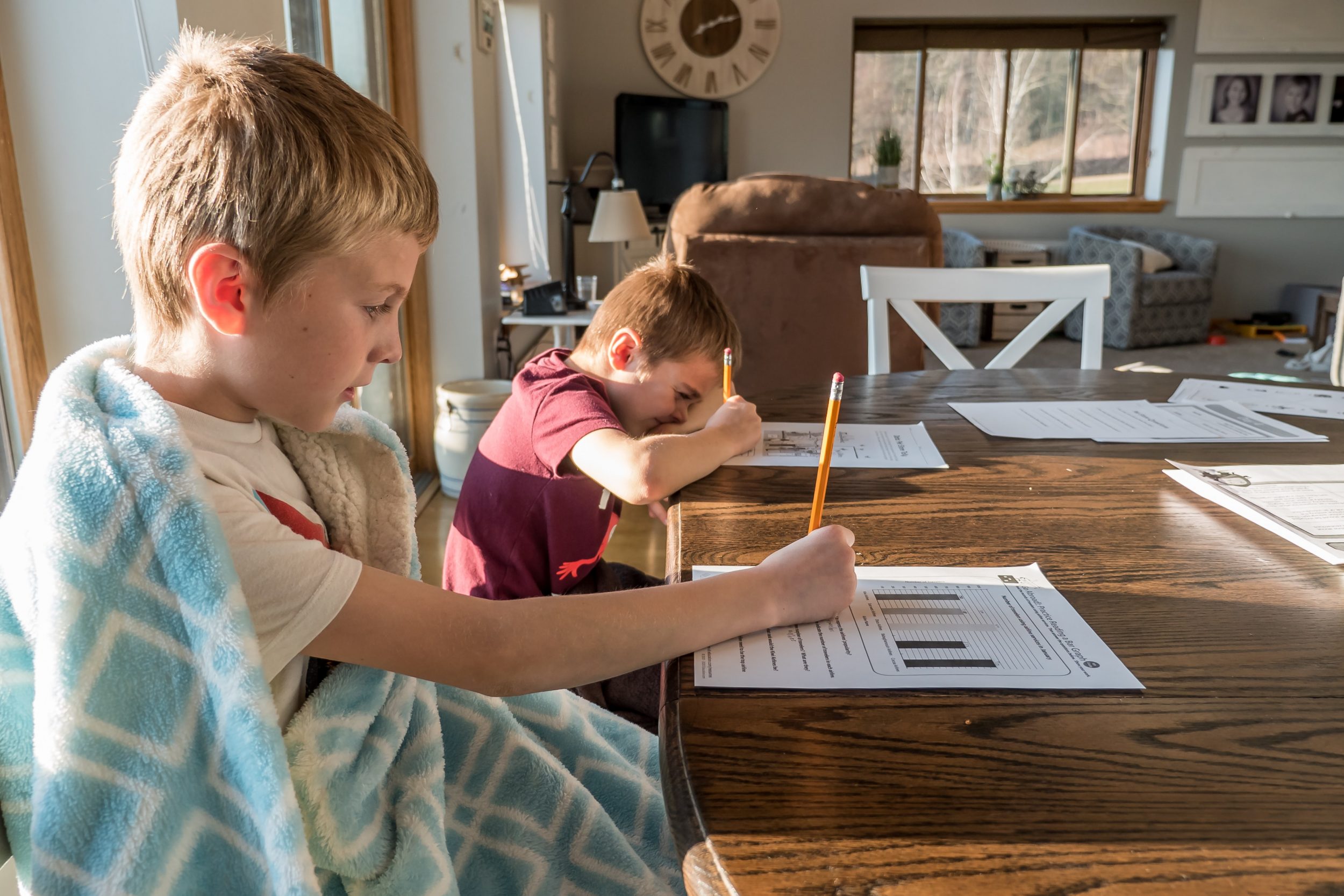

At stake is the strong claim that screen time is displacing social, cognitive and physical activities that are important for child development. Although concern over the effects of exposure to particular media contents remains, since media can have positive or negative effects, depending on content and context, and since all these effects are difficult to establish conclusively, the AAP urges that parents actively monitor the overall balance of activities in their child’s day, and ensure that time spent with media is actively interpreted and engaged with rather than passively absorbed. So the call on parents is crucial.

The new recommendations are not as simple as the headline-grabbing ‘2×2’ rule that has embedded itself into parents’ consciousness and consciences far beyond the US context for which it was designed. But they do fit much better with the present circumstances of family lives – more media at home, used for multiple and often valuable purposes, as part of diverse family cultures; certainly no longer something parents can simply police or ban. Indeed, many parents have embraced a media-rich home for their children precisely in the hope that this will bring real benefits and guide their children towards a future of digital work and digital opportunities.

Still, some critical questions arise in trying to match these recommendations to the evidence, on the one hand, and to the practical realities of family life on the other.

The evidence

Does the evidence really support the new AAP recommendations, as they claim? To check this out, I have read their lengthy technical report and their linked policy statements on younger children and older children and teens.

- The report reviews a large number of studies on the effects of media on children. Much focuses on negative effects, which addresses parents’ main concerns, although the AAP has made greater efforts than before to review evidence for positive effects.

- It’s hard to get around the familiar methodological problems. Notably, as it’s hard for researchers to control for all the factors that apply in particular children’s lives, as also they cannot expose children deliberately to potentially harmful media, and as research on long-term effects is sparse, critical questions arise as to whether the evidence base is as robust as one might wish. So the report is full of correlations (more screen time, less sleep) but correlations don’t always reveal direct or simple causation.

- Moreover, for all the issues addressed, there are many problematic gaps. There are studies on whether watching videos helps toddlers learn new words (answer: not really) but not on the social pleasures of singing and dancing along with a video. There are studies showing that many ‘educational apps’ are not very educational at all, but few on what children learn from the apps that do work. There’s plenty of studies showing the correlation between television viewing and childhood obesity, though little that nails television as the culprit – rather than a lack of physical activity (surely the real problem). And the evidence is stronger on the association between screens in the bedroom and loss of sleep, a point many parents in our research have already figured out for themselves, making a ban on screens in the bedroom seem advisable. But it’s noteworthy that the report says nothing about neurological development, given the popular belief that screens damage children’s brains.

- Somewhat surprisingly, it’s hard to find the evidence in the report for the specific new recommendation of a one-hour limit for 2-5 year olds, Just one study cited on the correlation between screen time and body mass index, for example. Just one study, too, it seems, underpins the claimed benefits of Skype interactions for 18 month olds, although already one headline concludes dramatically that American Academy Of Pediatrics Lifts ‘No Screens Under 2’ Rule

Herein may lie the AAP’s dilemma – there isn’t a robust body of research on the effects of digital media on children, yet parents want guidance now. So in their report the evidence, such as it is, is laid out. But the link from the evidence to the recommendations is not as strong as one would hope. No wonder that the AAP explained a few months ago that its approach will be conservative, recalling how long it took to recognise the harms of poor diet and arguing that the media – like diet – can be healthy or problematic, depending on how it’s managed.

The recommendations

Do the recommendations really provide parents with what they need to meet the challenges of today’s digital environment? Here I draw on the in-depth interviews with 70+ families from our research project, Parenting for a Digital Future.

- Counting screen time is still problematic. For parents with children who play several hours of sport and then like to collapse in front of a screen, the idea that such viewing will cause obesity must seem misplaced. For parents whose toddlers love to play in front of a noisy telly even though they’re hardly looking at it, counting hours will surely raise unnecessary anxieties. And for parents whose children are learning coding or creating their own video content or turning to YouTube to learn a new guitar chord, the lack of specificity about ‘screen use’ could be undermining.

- However, the new emphasis on children’s overall disposable time may be helpful to parents. For what matters is not so much how many hours children spend with screens but whether that takes too much time away from sleeping, playing, talking and being physically active. As Alicia Blum-Ross and I argued in our recent policy brief, parents might usefully stop watching the clock and instead ask themselves:

- Is my child physically healthy and sleeping enough?

- Is my child connecting socially with family and friends (in any form)?

- Is my child engaged with and achieving in school?

- Is my child pursuing interests and hobbies (in any form)?

- Is my child having fun and learning in their use of digital media?

- The first four of these seemed to us to capture parents’ deep concerns about their children. We added in the qualifier, ‘in any form’, because in the digital age it would surely help parents to focus less on how children communicate or learn and more on whether and what they communicate and learn, and what benefits this brings. And we added in the fifth question because digital media can indeed offer opportunities for fun, learning, connection and much more. Perhaps a future AAP report will examine whether these opportunities do, as many hope, bring genuine benefits.

In our research, we have been struck by how self-critical parents are of their own parenting practices, often defining ‘good parenting’ as ‘media-free parenting’ – which is tough in a media-saturated world where learning, work and social connections are increasingly mediated. They castigate themselves for not providing enough free play or sports outside, for handing a child a tablet when either child or parent is exhausted, and they tend to read time in front of a screen as ‘bad’ because it’s ‘screen time’ even when children are chatting, playing, or just relaxing after a busy day.

Behind a lot of the AAP’s evidence and recommendations is not so much the idea that screens are bad for children but that social, cognitive and physical activity is good for children. It would be interesting to see more emphasis on this positive point. For what parents really need is encouragement in these uncertain and pressured times. It seems to me that the advice they really need is to spend less effort counting screen hours or worrying about whether there’s a screen in the room where a child is studying or playing or, indeed, whether they’re a good enough parent – so they can be free to share in and enjoy lively, confident and pleasurable time with their children, whether or not there’s a screen involved.

This post was originally published on the Parenting for a Digital Future blog and is reproduced with thanks. It gives the views of the author, and does not represent the position of the LSE Media Policy Project blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Politcal Science.

4 Comments