Online campaigning is increasingly important in the run up to elections, but it is more complicated and less regulated than traditional campaign methods. LSE Professor in Politics and Communications Bart Cammaerts writes here about the ‘dark’ campaigning taking place online in advance of the UK’s General Election on 12 December.

In a previous piece at the start of the election campaigns, I predicted that while the mainstream media would be vicious and acerbic for Corbyn but lenient towards Johnson, the real dark horse race of this election would take place online, mainly through social media platforms and more specifically, through Facebook. Election coverage in the UK, especially in the written press, seems extremely skewed to the right. Particularly in this election, it seems to me that it is all gloves off and guns blazing when it comes to anti-Corbyn and anti-Labour campaigning journalism, to the extent that I wonder whether there shouldn’t be the same ‘special impartiality requirements’ for the written press as there are for broadcasting. These vicious attacks occur in a blatant, albeit transparent, manner and colleagues at Loughborough University have concluded that Labour has a ‘substantial deficit of positive to negative news reports’, whereas the Tories receive more positive than negative coverage.

What is less apparent and less transparent is what is happening in online campaigning, with limited information about the content that is being distributed, to whom it is being distributed, and the money that gets pumped into it, and who pays for what. What is clear is that elections have become a new cash cow for some social media platforms, Facebook in particular (Twitter has banned paid political advertising, and Google is restricting targeted political advertising). Facebook users’ individual data profiles contain personal and political information at such a detailed and profound level it is any campaigner’s dream to get access to this, and Facebook is all too happy to facilitate that. In 2017, UK political parties spent £3.2m on Facebook ads, up from £1.3m in 2015. It would not surprise me at all if this figure doubles again during this election cycle, especially since this is a relatively short campaign, which favours targeted mediated communication, especially in marginal or potentially winnable/defendable seats.

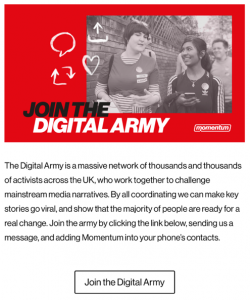

Labour’s digital campaign is two-pronged. On the one hand, it is running a more official online campaign, casting doubts on Johnson’s character, emphasising that the Tories cannot be trusted, and focusing more on campaign pledges. On the other hand, it is also running a more social media savvy campaign led by the digital army of Momentum, with lots of video content and memes being disseminated across social media platforms. From a cursory analysis, these seem to convey an image of Boris Johnson as an out-of-touch toff, an obnoxious extreme Tory, insensitive to the concerns of ordinary people, incapable of solving problems caused by the floods, out to sell the NHS to Trump, and funded by Russian money. A common strategy by Momentum is to use carefully selected media content, interviews of Johnson or his cabinet members, to support that depiction. Another distinct strategy is to give voice to the many and their everyday struggles. Brexit seems to be largely absent from both Labour’s and Momentum’s communication strategies.

Labour’s digital campaign is two-pronged. On the one hand, it is running a more official online campaign, casting doubts on Johnson’s character, emphasising that the Tories cannot be trusted, and focusing more on campaign pledges. On the other hand, it is also running a more social media savvy campaign led by the digital army of Momentum, with lots of video content and memes being disseminated across social media platforms. From a cursory analysis, these seem to convey an image of Boris Johnson as an out-of-touch toff, an obnoxious extreme Tory, insensitive to the concerns of ordinary people, incapable of solving problems caused by the floods, out to sell the NHS to Trump, and funded by Russian money. A common strategy by Momentum is to use carefully selected media content, interviews of Johnson or his cabinet members, to support that depiction. Another distinct strategy is to give voice to the many and their everyday struggles. Brexit seems to be largely absent from both Labour’s and Momentum’s communication strategies.

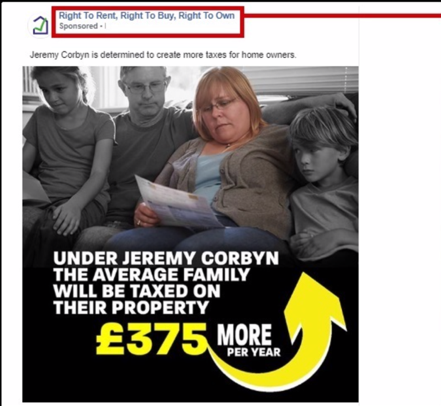

That is in sharp contrast with the Tory campaign online, where the focus is very much on ‘getting Brexit done’, which is not surprising. Another linked focal point in their online campaign material is immigration and how this will run out of control under a Labour government. Rebuttal and ridiculing Labour policy proposals, such as free internet access, is also a common tactic. Another theme that is being played is how lifelong Labour voters are now ‘backing Boris’, who of course is portrayed as a (goofy) man of the people.

Anti-Labour ads are also appearing online from obscure organisations, the BBC has found, such as ‘Parents’ Choice’, funded by former Tory minister Richard Tracey, or the ‘Fair Tax Campaign’, started by former Johnson aide Alex Crowley. Such stealth online campaigns using misinformation, lies and dark propaganda techniques cannot be linked directly to the Tory party, but they certainly fit their current campaign strategy.

Another example of the unethical behaviour of the Tories is the changing of the name of its campaign headquarters’ Twitter account during the party leaders’ debate to ‘factcheckUK’, in a deliberate attempt to mislead the public. Yet another example of this is the fake Labour manifesto website (http://labourmanifesto.co.uk) launched by the Tories a few days ago.

The Tories have clearly decided that the end justifies all possible means, which includes scrupulously peddling lies, misleading the electorate, and taking this country for a ride. It suffices to have a look at ex-Torygraph journalist Peter Oborne’s website ‘The Lies, Falsehoods and misrepresentations of Boris Johnson and his government’ to detect the pattern here.

Sure, Momentum also exaggerates (a bit), caricatures at time, or might occasionally use a leftwing populist slogan and engage in some billionaire bashing, but it does not lie, it does not deceive, it does not consciously pander blatant untruths to see what sticks. Both parties wage an online war of position, but there is only one party that plays really dirty and has left all political ethics and morality behind, and that is the Tory party.

This could be blamed on the lack of a regulatory framework for online campaigning in the UK, as the LSE’s Truth, Trust & Technology Commission noted one year ago. Without action, their final report concluded, we would risk going to ‘the polls with a regulatory framework that is as broken as the one that exists today’, and that is exactly what has happened. Maybe inaction in this regard served the interests of the ruling party? On the other hand, even with regulation in place, it would not have stopped the Tory party from unethical behaviour, especially as this post-truth strategy does not limit itself to the online context, but extends to its offline and media discourse too.

This post represents the views of the author, and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.