How do we think about vulnerability and risk within the network society? What metaphors do we use? LSE’s Dylan Mulvin and Simon Fraser University’s Cait McKinney explain some of the thinking behind their new article, “Bugs: Rethinking the History of Computing” (journal website and PDF), in which they look back thirty years to the days of floppy disks for some answers.

How do we think about vulnerability and risk within the network society? What metaphors do we use? LSE’s Dylan Mulvin and Simon Fraser University’s Cait McKinney explain some of the thinking behind their new article, “Bugs: Rethinking the History of Computing” (journal website and PDF), in which they look back thirty years to the days of floppy disks for some answers.

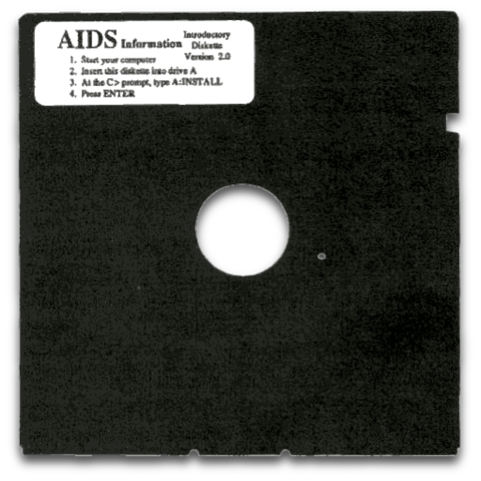

It’s December 1989 and you’ve received a floppy disk in the mail. The disk, labelled, “AIDS Information Diskette” promises useful advice about HIV and “up-to-date information about how you can reduce the risk of future infection, based on details of your own lifestyle and history.” You install the disk, which launches a quiz. Thirty-eight questions later, you get some cynical advice: “Buy condoms today when you leave your office.” It’s not that helpful but now you’re curious. You take the quiz again and get another result, “Danger: Reduce the number of your sex partners now!” Rude. You pay it no mind and go back to what you were doing.

A few days later, you start up your work computer and get an alert: “You are advised to stop using this computer. The software lease has expired.” To renew the software lease, you are told to send payment to PC CYBORG CORP of Panama City, Panama—either $189 for 365 further uses of your computer, or $389 for the lifetime of the hard disk.

A few days later, you start up your work computer and get an alert: “You are advised to stop using this computer. The software lease has expired.” To renew the software lease, you are told to send payment to PC CYBORG CORP of Panama City, Panama—either $189 for 365 further uses of your computer, or $389 for the lifetime of the hard disk.

Your computer has been infected with a Trojan horse virus, and what is widely acknowledged as the first ever piece of ransomware—though it long predates that particular name. Drawn from misappropriated mailing lists, recipients of the AIDS Information Diskette included HIV/AIDS researchers who had attended a World Health Organization conference on AIDS, subscribers to P.C. Business World (a UK magazine), banks, hospitals, and the United States’ National Institutes for Health.

The disk wreaked havoc on systems that it infected and the small but burgeoning community of anti-virus researchers responded swiftly. Soon a man named Jim Bates had created an antidote, called “AIDSOUT,” and a separate programme for de-encrypting seized files called “AIDSCLEAR.” The swift response was celebrated and documented in exquisite detail in The Virus Bulletin. Bates’s antidote was shared through the same subscriber networks that had been infected. Philadelphia’s Critical Path AIDS Project, an activist group, warned its members against installing the disk through its newsletter and electronic Bulletin Board System—relying on both analogue and digital networking to protect its service community.

It’s a peculiar episode. The AIDS Information disk would be noteworthy enough for its status as the first piece of ransomware. But it’s also noteworthy because it’s a part of a much larger, and surprisingly common phenomenon.

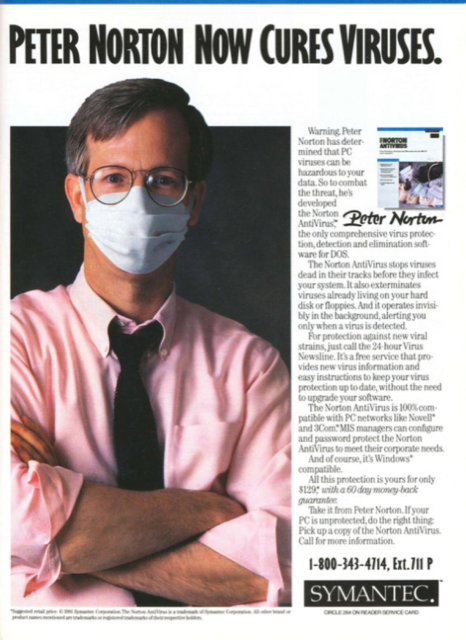

We have just published a new article on the history of computing and network cultures in the long 1990s. In the article we document the regular and pervasive ways that discourses of HIV infiltrated computing discourses. We found that throughout the decade, from the earliest days of computer viruses and anti-virus software, to popular culture, to government testimony, and public sector research, HIV was used as a metaphor to explain the dangers of networked connection.

In addition to the AIDS diskette, some of the earliest and most infamous computer “viruses” drew explicitly on AIDS, including viruses called simply “AIDS,” “AIDS II,” and “CyberAIDS” (all circa 1990). But these metaphorical uses quickly seeped into the wider culture and repeated throughout the decade. In 1989 U.S. Representative Wally Herger attested to the House Judiciary Committee while they considered computer virus legislation: “the problem of computer viruses and their cousins, the computer worm and the trojan horse, has become one of the primary topics of conversation within the computer industry….Some have even called [an attack on the ARPANET] the AIDS of the computer world.” In 1999 the National Research Council likened the sharing of data through “open networking environments” to the “spread of AIDS, noting new concerns about the trustworthiness of the people who constitute one’s social network and the dire consequences that could result from the indiscriminate expansion of one’s contacts.”

In addition to the AIDS diskette, some of the earliest and most infamous computer “viruses” drew explicitly on AIDS, including viruses called simply “AIDS,” “AIDS II,” and “CyberAIDS” (all circa 1990). But these metaphorical uses quickly seeped into the wider culture and repeated throughout the decade. In 1989 U.S. Representative Wally Herger attested to the House Judiciary Committee while they considered computer virus legislation: “the problem of computer viruses and their cousins, the computer worm and the trojan horse, has become one of the primary topics of conversation within the computer industry….Some have even called [an attack on the ARPANET] the AIDS of the computer world.” In 1999 the National Research Council likened the sharing of data through “open networking environments” to the “spread of AIDS, noting new concerns about the trustworthiness of the people who constitute one’s social network and the dire consequences that could result from the indiscriminate expansion of one’s contacts.”

The examples are widespread and our article is an attempt to thread them together. It’s part of our larger effort to rethink the history of computing through the perspective of marginalised experiences of illness and disability. To this end we document how computer users living with HIV responded to and refracted the virus metaphor, and offered models for interdependence, shared vulnerability, and coordinated response using digital tools—models that might be mobilized today.

The article is also an attempt to capture some of the more ignored ways we’ve come to consider the network society more broadly. Ransomware, if it begun in the 1980s, is more prevalent than ever, often affecting vulnerable institutions and communities with the most to lose. This year, more than a thousand U.S. schools were affected by ransomware attacks; hackers have held the servers of both Baltimore and Atlanta hostage; and the WannaCry attack cost the NHS upwards of £90 million. Naturally, the market for “cyberinsurance” is growing. And ransomware is just the start: we are regularly reminded of our vulnerability to networks, whether in the loss of data, the viral spread of misinformation on social media, or our own susceptibility to the spirals of fervent belief produced in an ideological echo chambers.

Based on our research into viruses and sexualised metaphors of infection, we have been particularly intrigued by the growing fear around public USB ports and a new market for “USB condoms.” As NBC described it (rather bluntly) in 2013:

“Worried about plugging your device into an unfamiliar port and exposing it to horrible viruses or trojans? Simply put this “USB condom” between the male and female ends before docking and the only thing transmitted will be safe, clean electricity.”

Damaging ideas about stigma, hygiene, sexuality, and personal responsibility honed in the AIDS crisis continue to govern how we think and talk about digital networks and infrastructures.

We undertook our research because we are historians concerned with the ways our cultural conceptions of vulnerability shape our experiences and expectations of technology. The dangers of the network society are part of being connected to others in interdependent relationships that can also be grounds for solidarity and survival. In this way these dangers will never be fully eliminated or preventable, and are part of being in proximity with others. As dangers endemic to social connection, they have to be understood in their historical and social context. We hope our project is a small contribution to this understanding.

This article represents the views of the authors, and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.