The global anti-racist protests that George Floyd’s killing has provoked, combined with the strong focus on our local area as a result of the COVID-19 lockdown, offer opportunities to better understand the legacies of slavery and colonialism immediately around us. LSE’s Wendy Willems examines the intersection of race, space and media in her local Woolwich neighbourhood in South-East London.

The global anti-racist protests that George Floyd’s killing has provoked, combined with the strong focus on our local area as a result of the COVID-19 lockdown, offer opportunities to better understand the legacies of slavery and colonialism immediately around us. LSE’s Wendy Willems examines the intersection of race, space and media in her local Woolwich neighbourhood in South-East London.

Recent global #BlackLivesMatter protests have not only drawn comparisons between similar racial geographies across the world but have also made links between histories of slavery and colonialism and contemporary forms of racism. Mainstream media are not in the habit of providing historical context. Instead, they often detach and disconnect current events from a longer historical background, which serves to evade responsibility for the past.

For example, during the occupation of white-owned farms in Zimbabwe in the early 2000s, former colonial power Britain was reluctant to acknowledge responsibility for the skewed distribution of land in favour of white settlers, while mainstream media coverage of the occupations reproduced colonial discourses which presented white farmers as indispensable and Black occupiers as incapable of farming and destructive of both the economy and the environment.

Significantly, George Floyd’s killing has put the spotlight on anti-Black racism in Britain. The dramatic act of ‘historical poetry’ ―in the words of Bristol’s mayor Marvin Rees― which recently saw the toppling and ‘burial’ of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in a Bristol canal has provoked a debate on the celebration of colonial heroes. Possibly more importantly, it has forced connections between Colston’s continued presence in our urban landscape (despite decades of campaigning for its removal) and Britain’s record of racialised police violence, racial profiling in arrests and the much higher COVID-19 death rate amongst Black communities.

Global and local connections

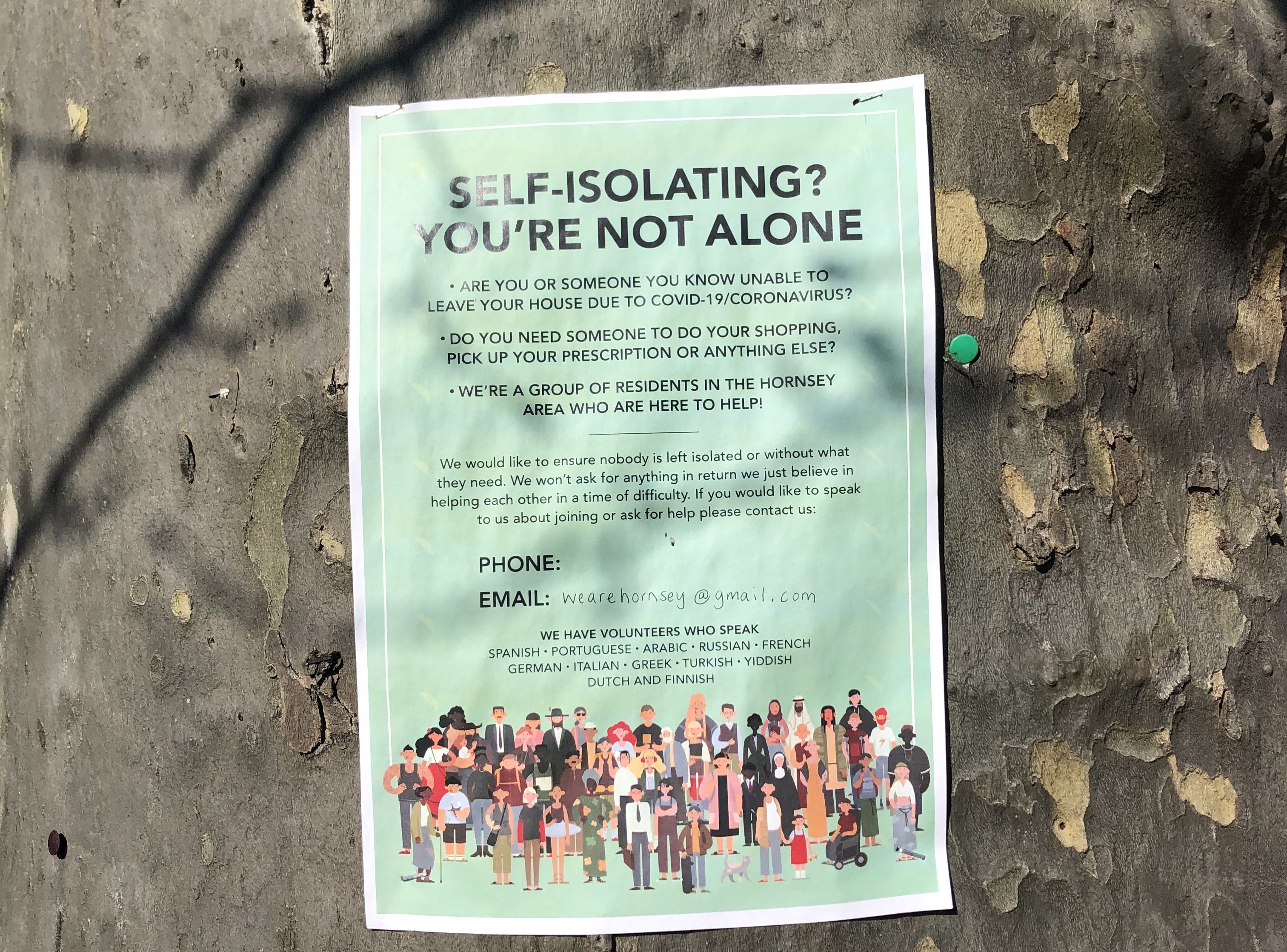

As part of the COVID-19-induced lockdown, those of us privileged to be able to stay home have been working, schooling, exercising and protesting at home by taking a knee in solidarity with George Floyd. The pandemic has encouraged us to set up local mutual aid groups, to buy from local shops in order to avoid empty shelves in supermarkets and to make more use of local leisure spaces. In recent months, many of us have primarily stayed within our local areas, including attending local #BlackLivesMatter marches in order to avoid public transport to travel to bigger central London protests.

Against the background of this collective shift in attention to our local surroundings and in response to the spectacular removal of Colston’s statue, Labour councils announced on 9 June that they will review all statues and monuments in local areas. The leader of my own Royal Borough of Greenwich in South-East London, Cllr Danny Thorpe, admitted that “[i]t is an uncomfortable truth that our borough, with its rich Maritime history, has ties to the slave trade. We will be reviewing the whole of our public realm to identify these links and develop a way forward. Our history is important, and we are not looking to rewrite or forget the past. But we do have a responsibility to question and discuss the place of commemorative structures from bygone eras in our borough’s future.”

A few days after this announcement – amidst all forms of solidarity, ranging from issuing mild, performative statements to making firm commitments to reparations – following the example of Washington DC’s Mayor Muriel Bowser, Greenwich Council launched a yellow #BlackLivesMatter mural in General Gordon Square in Woolwich to affirm its “commitment to eradicating racism and discrimination in our society”.

Locating this mural in General Gordon Square produces both a historical and contemporary conundrum. Major-General Charles George Gordon was born in 1833 in Woolwich and counts as one of Britain’s key imperial heroes. After serving in the army in the Crimean War and in China and Egypt, he died in 1885 resisting the rebel army of the religious leader, Muhammad Ahmad, in Khartoum, Sudan. To pronounce that #BlackLivesMatter in General Gordon Square appears to be a contradiction-in-terms. If Black lives mattered, General Gordon Square would by now have been renamed. But because it has not, the square continues to participate in celebrating Gordon’s imperial legacy.

Luxury living amidst ‘rich’ imperial history

This imperial legacy is also visible in an upmarket residential estate, now known as Royal Arsenal Riverside, 600 meters north-east of General Gordon Square and central to Woolwich’s rapid gentrification (fuelled by the highly anticipated Crossrail Station). Comprising 1,285 hectares, the Royal Arsenal produced the bulk of armaments and explosives for the British army from the early 17th century until the factory’s closure in 1967. The British Empire depended on the Royal Arsenal, as the following women factory workers’ song demonstrates:

Where are the girls of Arsenal?

Working night and day

Wearing the roses off their cheeks

For precious little pay

Some people style them ‘canaries’

We’re working for the lads across the sea

If it were not for the munition lasses,

Where would the Empire be?

A small 2011 award plaque from the Institute of Engineers on a building in No 1 Street recognises the “many important mechanical innovations” initiated by the Royal Arsenal which contributed to “the growth of the British Empire”. The estate still hosts a number of cannons interspersed with historical buildings that carry names which refer back to the original purpose of these buildings, such as the Grand Store which was used as a warehouse to store guns, shells and cannon balls. New high-rise, river-facing apartment blocks carry names such as ‘Imperial Building’ or ‘Navigators Wharf’ which hint back to Britain’s colonial history. The estate is branded as a desirable place to live because of its ‘rich history’. As a glitzy Berkeley Homes marketing brochure featuring a nearly all-white line-up of potential residents reads: “Royal Arsenal Riverside is an award-winning blend of old and new: historic listed buildings meet contemporary designs. It’s this unique mix which makes this a vibrant and exciting place to live”.

Despite its perceived success as a public space, General Gordon Square by virtue of its name and its revival of memories of Empire does not appear to welcome those who have been at the receiving end of British colonialism. Similarly, the Royal Arsenal Riverside development glorifies Britain’s military innovations and successes without acknowledging the many lives lost by the gun powder, cannon balls and bullets manufactured at the site for centuries. Instead of confronting this history in an explicit manner, heritage has been transformed into a desirable but bland and contextless aesthetic. The refusal to explicitly acknowledge these horrific historical legacies and to continue celebrating imperial heroes such as General Gordon is not simply a symbolic erasure but intimately tied to, and reproduced by, contemporary and material forms of racism, as associated with processes of gentrification or incidents of police brutality.

They are here because you were there

If we leave Royal Arsenal Riverside and return to General Gordon Square and walk approximately 300 metres north-west to Calderwood Street, we find another telling example of how Black lives do not matter. With every life lost in recent years as a result of racialised police violence, my thoughts return to Wednesday, 27 September 2006 when I learned that Frank Ogboru died the previous evening outside the block of flats that I was living in at the time.

Frank Ogboru was visiting friends in London from Nigeria. Like George Floyd and so many others, he died after a policeman kneeled on his neck and his last words, too, were “I can’t breathe”. His case was examined by the Independent Police Complaints Commission (IPCC) but dismissed by the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) on the basis of insufficient evidence, despite a CCTV recording and mobile phone recording of his killing being available. Unlike George Floyd’s killing, Frank Ogboru’s death was a minor event that was only briefly reported in the press. His life did not seem to matter.

In contrast, the killing on 22 May 2013 of a white soldier, Lee Rigby, 500 meters south-west of General Gordon Square in Wellington Street, achieved global headlines after his murder was framed as a terrorist attack. One of his killers, Michael Adebolajo, justified the killing as follows in a video recorded by a bystander: “The only reason we have killed this man today is because Muslims are dying daily by British soldiers”.

News coverage emphasised the brutal nature of the killing by two British-Nigerian men and declared soldier Lee Rigby a national hero. For example, The Daily Mail led with “You and your children will be next’: Islamic fanatics wielding meat cleavers butcher and try to behead a British soldier” while The Daily Telegraph headlined “A British soldier has been butchered on a busy London street by two Islamist terrorists”.

The nature of these two events as well as the meanings attributed to them in mainstream media cannot be understood outside the history of slavery and colonialism which established race as a key tool of domination. These also demonstrate the connectedness of Britain’s history to those of others via the Empire, which sociologist Gurminder Bhambra suggests needs to be made more visible. As Stuart Hall also reiterated, “[t]hey are here because you were there. There is an umbilical connection. There is no understanding Englishness without understanding its imperial and colonial dimensions”.

In other words, Frank Ogboru and Michael Adebolajo were here because Gordon was there. Woolwich’s current demographic makeup (around 30 percent of its population identifies as Black African/Black Caribbean) has been profoundly shaped by the history of Empire. It hosts a significant community of ex-Gurkha soldiers from Nepal and other communities with origins in Bangladesh, Pakistan, India, Nigeria and Somalia.

While this umbilical connection may live on in the Commonwealth, history continues to be taught as if it was disconnected from this longer history. News depictions of global events keep on being reported as if they were not impacted on by these histories. Contemporary racism ― whether reproduced by police brutality, skewed media coverage or gentrification ― is a product of centuries of slavery and colonialism. Race is not an optional analytical lens that can be taught in the last-but-one class of a university module or a secondary school curriculum. As decolonial scholars remind us, race as a socially constructed category of difference is constitutive of our world.

Literally two streets away from our home lived William Wilson Hornsby (1793-1849), a slave owner who owned ten enslaved people in St John, Jamaica. While those enslaved did not receive any compensation for the freedoms they were denied, Hornsby received £172 compensation (over £22,000 in today’s value) as part of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833. This sum helped to build the wealth of his descendants and was financed by taxpayers in Britain and across the Empire. The debt incurred as a result was finally payed off by the Treasury in 2015. The history of slavery and colonialism is not just ‘out there’ in a stuffy history book or museum: it is right on our doorstep. Teaching young people how our local areas connect to these larger histories does not only bring racism home, but can inspire the practice of anti-racism as well.

This article represents the views of the author, and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Jonathan Bart

Fantastic article Wendy. So relevant, practical, and well researched. Love the accessible style, the way you’ve interwoven theory and important (yet not well known) historical facts. Thank you for reminding us of the way large stories get played out in the daily mundane streets around us. Thank you for reminding us not to get sidetracked by narratives in the US, because brutal racialised deaths that go on here all the time in England and do not get talked about. As you say, race is not an ‘optional lens’. This is a powerful, very readable piece that deserves wide circulation: I feel there are many more areas of London that could do with the sort of examination and research you’ve done here.

Fantastic article. So few people seem to actually understand the impact of colonialism in present day. As a BME person it does get a bit tedious trying to educate people on these topics and despite everyone being up for improving their mindset, nothing seems to change. It gets quite depressing.

I dont know if you’re still based in Woolwich but its comforting to know someone in my neighbourhood has your perspective.