Throughout the current COVID-19 health crisis, governments have acted swiftly to shield corporations and other organizations against legal liability. In this blogpost, Dylan Mulvin, assistant professor at the LSE’s Department of Media & Communication, digs into the history of liability, and its companion, the “tort,” to show that they can tell us a great deal about the struggle to distribute responsibility, how we sort the causes and effects of technological harms, and where we find recourse for wrongs.

Throughout the current COVID-19 health crisis, governments have acted swiftly to shield corporations and other organizations against legal liability. In this blogpost, Dylan Mulvin, assistant professor at the LSE’s Department of Media & Communication, digs into the history of liability, and its companion, the “tort,” to show that they can tell us a great deal about the struggle to distribute responsibility, how we sort the causes and effects of technological harms, and where we find recourse for wrongs.

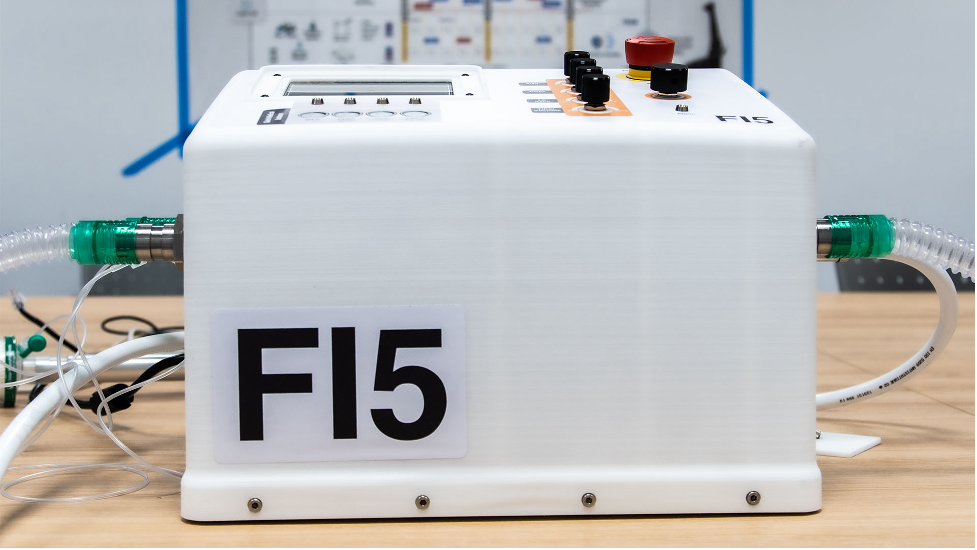

In April, amid the urgency to produce, acquire, or reinvent ventilators to meet the demand of hospitals overrun with Covid-19 patients, there was a sticking point: what if someone screwed up? In the rush to produce new ventilators outside of the typical regulatory regime, could companies like Rolls Royce, Dyson, and even F1 racing outfits, be held legally responsible for someone who died? The question of liability, in other words, haunted what was—or seemed to be—the untempered race to respond to the crisis.

It didn’t take long: governments quickly reassured participating companies that they would be indemnified from liability for any failures of these upstart ventilator projects and that fears of being on the hook for wrongful death and personal injury lawsuits ought not to chill their desire to “pitch in.” Here in the UK, it was reported that the UK government would shield any company from lawsuits over any ventilator malfunction or intellectual property theft. As one source said at the time:

“We’re talking about accelerated production of what is a highly complex piece of kit,” said a person involved in a ventilator project who asked not to be named. “We wanted it to be recognised by government that the work we’re doing is under incredible time pressure and we needed assurances around indemnity. Now it’s sorted.”

Such concerns neither began nor ended with ventilators. Throughout the crisis governments have extended reassurances to businesses, employers, universities, and vaccine manufacturers that they would be protected from liability, should businesses choose to open, call their workers back to the office, open their classrooms, or produce an efficacious vaccine. And this week we heard again that one of the irreconcilable differences in the US congress currently, preventing further economic stimulus, is a demand from the Republican leader of the Senate, Mitch McConnell, for a wide-reaching “liability shield” against personal injury lawsuits related to COVID-19.

In this particular year, knowing that this kind of legal protection is often called “immunity” seems like a cruel linguistic joke. But it is also worth pursuing this coincidence: why is it that this biological metaphor is extended to organizations (corporations) for threats (lawsuits) that are otherwise, normally, considered to be a tool of justice and accountability? What do such terms, their extension, and their suspension, mean for a larger understanding of harm and responsibility?

Liability law

For the past few years, as part of my research into the history of technology and the cultural history of the 1990s, I’ve taken an interest in liability law. I realize this is a bit like writing, “as part of a larger interest in concrete, I’ve taken up the small hobby of collecting egg cartons.” But in projects dealing with the Y2K crisis (some research here [pre-print], in a recent issue of the Annals of the History of Computing) and mobile and computer screen “night modes” (here), I frequently found myself reading legal journals, legislation, and debates about the adjudication and determination of harms. I am fascinated by cases where those harms were successfully attached to specific technologies. As is more common, any attempt to name a specific harm usually slides off those technologies, to be dumped in the swamp of “unfortunate side-effects” or the even more diffuse “culture of carelessness.”

I believe that liability, and its companion, the “tort,” can tell us a great deal about the struggle to distribute responsibility, how we sort the causes and effects of technological harms, and where we find recourse for wrongs. Tort law is an infamously squishy topic. In general, it refers to civil lawsuits where the law provides some framework for remedying a “wrong.” As I and others have argued tort law and liability lawsuits can often expose prevailing social norms about what constitutes an unacceptable wrong, what constitutes fair compensation for being wronged, and what forms of injury and vulnerability can gain recognition. Torts are meant to be a last resort, but the threat of a largescale lawsuit still shapes, both actively and passively, relationships between individuals and the institutions around them. In lives lived through the murky indeterminacy of technologies over which we can exercise meagre control and, then, only through dwindling channels, liability remains a major conditioning force of what is determined to be socially acceptable or ultimately noxious.

Harms

Here, I have been guided by the work of Lochlann Jain. In Injury, Jain brilliantly argues that liability law not only shapes the legal and corporate understandings of care, neglect, and responsibility, but also shapes how the exposure to harm will radiate through the design, manufacture, use, and sale of products:

“[T]he law does far more than recognize, measure, and compensate injuries. It does the political and social work of determining what will count as an injury and, ultimately, how it will be distributed through product designs.”

For Jain, and those of us inspired by this approach, the goal then is to track how certain kinds of injury come to be recognized. But we also look at how, for whom, and when the exposure to harm becomes normalized and under what conditions does the distribution of liability get reshuffled.

For decades, the “litigiousness” of Americans has become a cultural stereotype. It is also regularly leveraged to reinforce a corporate-friendly and victim-blaming agenda that has helped build a bulwark against liability through the caricature of those who suffer injury as money-seeking malcontents. As Jain writes:

“Tort laws hold a peculiarly vital place in the United States, given–undoubtedly as a result of––the lack of universal health care coverage, the dearth of regulatory bodies. . . and the particular qualities of money, which can mutate in purpose from compensation to punishment.”

In societies with such narrow means for harm-mitigation it should come as no surprise that the limited outlet of the legal system has come to play the role of an emergency safety net—even if its rewards often look like lottery winnings more than systematic fixes to endemic neglect.

Liability then and now

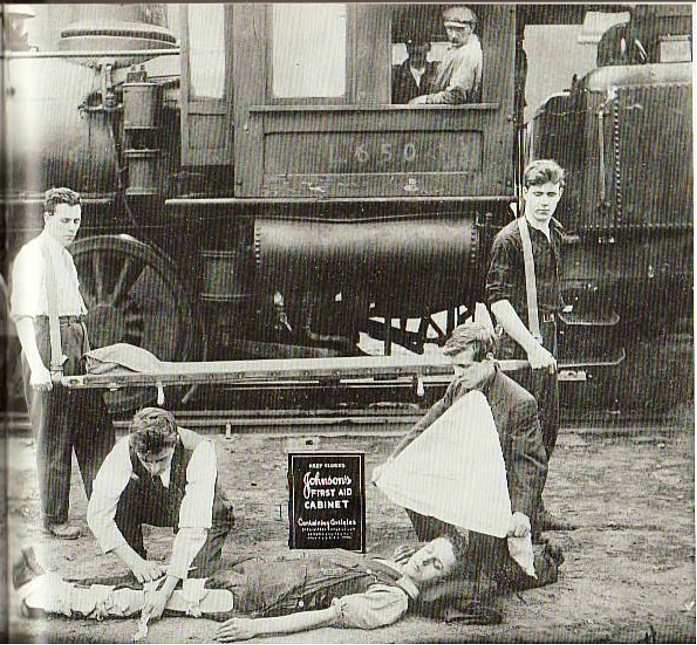

This story of American reliance on lawsuits is also historically specific. In the 19th century, an individual – a consumer, or a worker, or a train passenger – was unlikely to see any of their injuries recognized by a court. As the legal historian Lawrence Friedman, and the legal anthropologist Laura Nader (related, indeed) show, successful tort claims followed from the increased political clout of organized labour, and workplace injury claims paved the way for the recognition of injuries more widely. Insurance companies, too, provided a safety net for corporations; the latter could now obtain from the former policies against the likelihood they would be sued. Getting sued became a part of the cost of doing business and the emergence of legal last resort – as a potential windfall for any victims– became an excuse for lawmakers to avoid other regulatory interventions. Torts, insurance, and injuries could now all be included under the larger heading of the cost of progress: innovate, harm, pay, and move on.

Just as liability law indexed the changing relationship between corporate power and consumer recourse in the 19th and 20th centuries, it continues to map the institutional recognition of responsibility and vulnerability. Everywhere you look right now, liability shapes the horizon of technological development, use, governance, and regulation. It’s not just the manifold crises associated with Covid-19. Commentators and scholars in legal studies and media and communication studies have, in recent years, debated the role of Section 230 of the 1996 Communications Decency Act (CDA) in laying the foundation for the contemporary ecosystem of social media platforms in the United States. The provisions of Section 230 provide platforms the right, but not the responsibility, to remove content, which was meant to encourage early intermediaries (like ISPs or web portals), in the earliest days of the web, to take an active role in keeping their domains “clean.”

But, as a result of its broad legal interpretation, Section 230 has had an outsized influence on the ideology and corporate governance of platforms, while continuing to push the cost of platform openness to the ugly and dehumanizing labor conditions of content moderation. As Danielle Keats Citron and Mary Anne Franks write:

Regrettably, state and lower federal courts have extended Section 230’s legal shield far beyond what the law’s words, context, and purpose support. Platforms have been shielded from liability even when they encourage illegal action, deliberately keep up manifestly harmful content, or take a cut of users’ illegal activities

Section 230 is a remarkable artifact: a seemingly minor but misbegotten section of a larger, problematic effort at media regulation. It’s noteworthy not only because of what it provides platforms – latitude to remove content – but what it protects them from, namely civil liability. It’s ironic, then, that section 230 has recently become the target of conservative backlash, as the very same people calling for radical tort reform, and widespread legal immunity, are also calling for the end of the immunity protections of Section 230.

Liability—its enforcement, as well as its suspension—can serve as an especially useful lens for understanding how risk and responsibility are managed and distributed in moments of crisis. When we look at moments where liability holds, we can view the contours and of legible harms. Perhaps more tellingly, the move to immunize companies and employers from liability can also expose the limits of legible vulnerability. But liability law provides is inadequate for true social repair and it is impossible to fully account for the ways it has mutated our understanding of harm and vulnerability, reducing both to financial exposures and awards. Just as the immunization against legal liability should give us pause, we might want to closely follow the changing shape of liabilities as we continue to seek out ways of understanding how society is molded by and through the uneven sharing of vulnerability.

This article represents the views of the author and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.