The European Commission recently proposed two legislative initiatives: the Digital Services Act and the Digital Markets Act to upgrade the rules governing digital services in the EU. In this blog post, LSE’s Damian Tambini looks ahead at the EU legislation, and the outlook for UK media policy as it charts a course outside the EU in 2021.

The EU recently published two huge pieces of media related legislation: the Digital Services Act that sets out a detailed regulatory framework for protection of user rights online; and the Digital Markets Act that is a new set of competition rules aimed at making digital markets more competitive. Though there is a danger they will be watered down in the process of becoming law, these measures could be a huge step forward in the framework for tech regulation not only in the EU but globally.

The tech platforms have strong economic incentives to support the establishment of global standards. If as large and influential market as the EU sets out norms for content moderation and liability, the world – or at least the democratic world – may well follow. The UK is also legislating on the same areas: the Online Harms Bill has been pending for some time now, and new competition legislation is expected following the publication in December of further advice from the regulator.

Clearly this is a pivotal moment: how is the policy debate shaping up in this and related areas as we enter 2021? And will the UK follow the EU lead, or chart its own path?

This is the end of Internet 1.0.

One thing is clear: unlike the previous regime under the e-Commerce Directive and the AVMS Directive, the pending regulation is not driven by a quest only for economic growth and innovation. The texts speak more about fundamental rights than they do about growth or innovation, and the legislation was preceded by a clear acknowledgement by Commission President Ursula Von Der Leyen that Europe has in the past decade faced a crisis of democratic legitimacy, in which new internet services have very much been implicated.

The Digital Services package is presented as a core plank of the Democracy Action Plan, a set of proposals to protect democracy from perceived threats of propaganda and disinformation. For example, the Plan sets out a co-regulatory backstop for the self-regulatory code of practice on disinformation, which would be a stiffening of the EU’s light touch approach, but it seeks an accommodation between platforms and democracy across a wide range of issues.

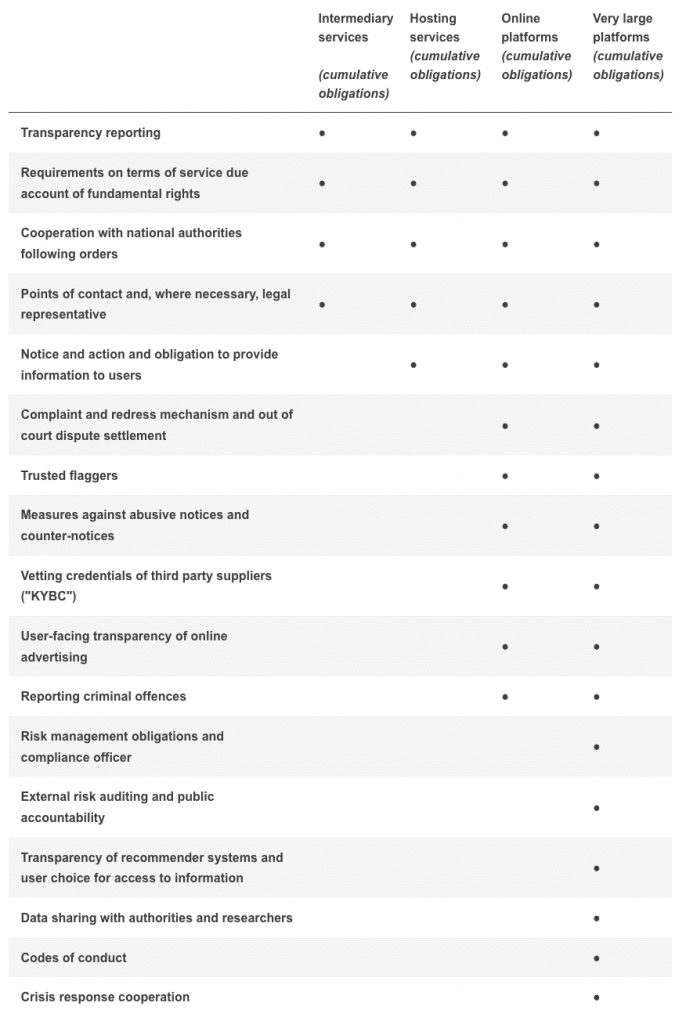

Whilst all platforms must observe some rules, such as transparent reporting, the new approach doesn’t establish identical rules for all intermediaries, but a graduated approach of more obligations for the most powerful. The EC summarised the new regime according to a sliding scale based on the level of editorial control and market power.

This sets the framework for a new phase of liberal democracy and media power

If the future of capitalist liberal democracy is online, then these pieces of legislation are a bellwether for the future of European democracy, and how it balances market, state and civil society and constrains private control of speech. The two pieces of legislation represent two solutions to the question of the public interest: legal regulation and market empowerment. There is an acknowledgement that platforms have undermined user rights, the public interest and democratic legitimacy, but there is potential in the debate and consultation of coming months, of shifting the slider between state and market responses.

there is potential in the debate and consultation of coming months, of shifting the slider between state and market responses.

There also remains an open question about the role of civil society, which could be crucial to the legitimacy for this new regime of speech control. The DSA sets out a social contract between platforms and society, which will determine where the power lies over censorship and propaganda. There are proposals for transparency, and to encourage platforms to enlist trusted flaggers such as fact checkers: can this offer a third way between state and private censorship which enables civil society actors to be involved? There remains the knotty question of how these arms-length bodies will be able to assert themselves against powerful platforms. How can they be independent and sufficiently funded?

The Digital Services Act package – which includes both the DSA and the DMA – will now be subject to scrutiny by the European Council (comprised of ministers of member states) and by the European Parliament. This will be a long haul. It is not yet clear if the UK will seek to exploit its supposed post-Brexit nimbleness to establish a regime in contrast to the legislation, but in any case, it is arguably the German example that already sets out a prototype for the DMA.

Meanwhile, the Atlantic seems to be widening

In the United States it is the courts rather than Congress that are making the weather on tech regulation. In December, the Federal Trade Commission announced a new antitrust action against Facebook supported by the attorneys general of the overwhelming majority of states in the US. This may be the most effective route to tech accountability and trust busting, but it might be argued that judge-made law is not the right path if the objective is a fair and legitimate system of media accountability in the new digital world.

Of course, the platforms themselves are players. By developing their own codes of conduct, content moderation appeals processes and transparency procedures, they intend to see off regulation, and pre-empt any undertakings a regulatory may order. What self-regulation might do however is invite audit of the effectiveness and independence of such processes. Self-regulation often becomes co-regulation, which is what the DSA effectively proposes.

Together, the new obligations on platforms aim to make them much more responsible for fundamental rights, arguably massively extending the horizontal effect of the European Court of Human Rights, and the scope of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the EU, and opening a wide gulf between these European approaches and the more hands of approach of the US First Amendment.

The Post-Brexit Trade Agreement liberalises trade in networks but not content

The telecommunications directive package on access, interconnection, authorisation and universal service is within the scope of the new UK-EU trade agreement, and therefore there will be mutual market access in telecoms. Audio-visual media services are only mentioned in order to specifically exclude them from the agreements. This is therefore a strong assertion of information sovereignty on the part of both parties. But given the DSA and the agreement the UK now has all to play for: it can choose some form of progressive solidarity with other liberal democracies in an attempt to work together to shore up embattled institutions of liberal democracy. Of it may attempt to court the platforms by offering them a more liberalised regulatory environment.

Public service media have had a short term shot in the arm, but long term there appear to be underlying conditions

The BBC and other public service broadcasters have held up well during the current crisis. Users have sought comfort and trust in familiar news sources. After the general economic crash hit commercial revenues hard, there has been something of a revenue recovery in public service media such as ITV and Channel 4. Threats to the BBC license fee have abated, at least temporarily. But broadcast performance has not benefited as much from the stay-at-home message as the platforms and streamers have. Increasingly, public service media such as the BBC, Channel 4 and other public service providers argue that they should be made more prominent, and that democratic legitimacy and governability depends on it.

The crisis of journalism continues

Elsewhere, the crisis of journalism continues, however, and other providers of public interest information such as members of the Journalism Trust Initiative rightly argue that they too deserve to receive benefits of prominence and discoverability. In the UK, government and parliament have generally shied away from the issue of press reform since the stalled Leveson process. The regulatory framework of regulated self-regulation under the Royal Charter, amazingly, remains in a state of suspended animation as it approaches its 10-year anniversary this year. A change of government, or an escape from the crisis that engulfs the current regime, could change all that if pressure built either to implement or to repeal the Charter or the relevant clauses of the Crime and Courts Act.

Europe, as it finally grasps the nettle of tech regulation, does so within a well-established European tradition in which freedom of expression is a conditional, qualified right.

Government has committed to implementing some of the recommendations of the Cairncross Review, including regulating the terms of trade between online intermediaries and the news providers to ensure a fairer revenue split. This was supported by the Competition and Markets Authority in their report on the work of the proposed new Digital Markets Unit.

All of this occurs within a framework that is set not only by competition rules but by tax incentives. The Government Response to the Cairncross Review agreed to extend some tax breaks for news providers, extending a VAT exemption previously guaranteed for newspapers to online news outlets. Like the new CMA proposals, such a change would require government to define a relevant news publisher, which government and parliament have generally resiled from doing.

In the short term, all eyes are on the COVID-19 pandemic. Disinformation about the virus and public resistance to measures such as lockdowns have led to controversy about censorship by governments and platforms. Early concerns about censorship clampdowns have been justified in a minority of countries, but eventually the ongoing disinformation and trust crisis will only be solved by a systemic approach, and cross party commitments to building new deliberative institutions to accommodate liberal democracy with new media.

What does all this mean for progressives?

Europe, as it finally grasps the nettle of tech regulation, does so within a well-established European tradition in which freedom of expression is a conditional, qualified right. This view, which is clearly set out in the foundational principles of the Council of Europe, contrasts with the approach of the US, which is profoundly suspicious of content discrimination and institutional media rights. In global terms it is the European view of freedom of expression, set out in the principles of international human rights law, that ultimately must prevail if a truly multilateral approach to tech regulation is to prevail. Human rights principles, as former UN Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of freedom of opinion and expression David Kaye has argued, must underlie future regulation in this area. Media policy remains a key battleground for the values of liberal democracy and progressives should support these European attempts to renew those underlying values and rights.

This article represents the views of the author and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Image credit Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay