Carlos Carrasco-Farré, a researcher at ESADE Business School, writes here about the differences in reporting style between reliable news sources and misinformation, and the need for quality news providers to resist the temptation to lower their standards in order to attract attention.

Carlos Carrasco-Farré, a researcher at ESADE Business School, writes here about the differences in reporting style between reliable news sources and misinformation, and the need for quality news providers to resist the temptation to lower their standards in order to attract attention.

The change from printed and televised news towards the digital world has caused a radical adjustment in the traditional media industry, challenging media companies’ business models and forcing them to innovate. Since many struggle to reach the same audiences and revenues as they got before the Internet, they may be tempted to pursue different strategies to achieve online virality. However, these strategies are sometimes similar to those followed by misinformation sources, which may have unintended societal consequences beyond the financial performance of individual media organizations.

Existing evidence shows that misinformation spreads six times faster than reliable news through social networks. The main reason is because misinformation leverages psychological manipulations to achieve higher virality rates. For example, we know that content that is highly emotional is more viral. Similarly, articles and headlines that appeal to the reader’s moral values by implying that the social group to which the reader belongs (nationality, gender, religion, etc.) is threatened by some external actor are also shared more often on social media. At the same time, social media usage is usually an individual and out-of-work activity. Therefore, users try to avoid employing too much effort in discerning what is real and what is not. They do so by relying on cognitive heuristics – mental shortcuts – that are often hijacked by malicious actors to become more viral. One of the most prominent examples is employing a linguistic style that requires less cognitive effort to be processed; that is, with less grammatical complexity and lower lexical diversity. Again, this is confirmed by the fact that simpler messages are more viral. Together, the aforementioned strategies conform what we call “the fingerprints of misinformation”.

The fingerprints of misinformation

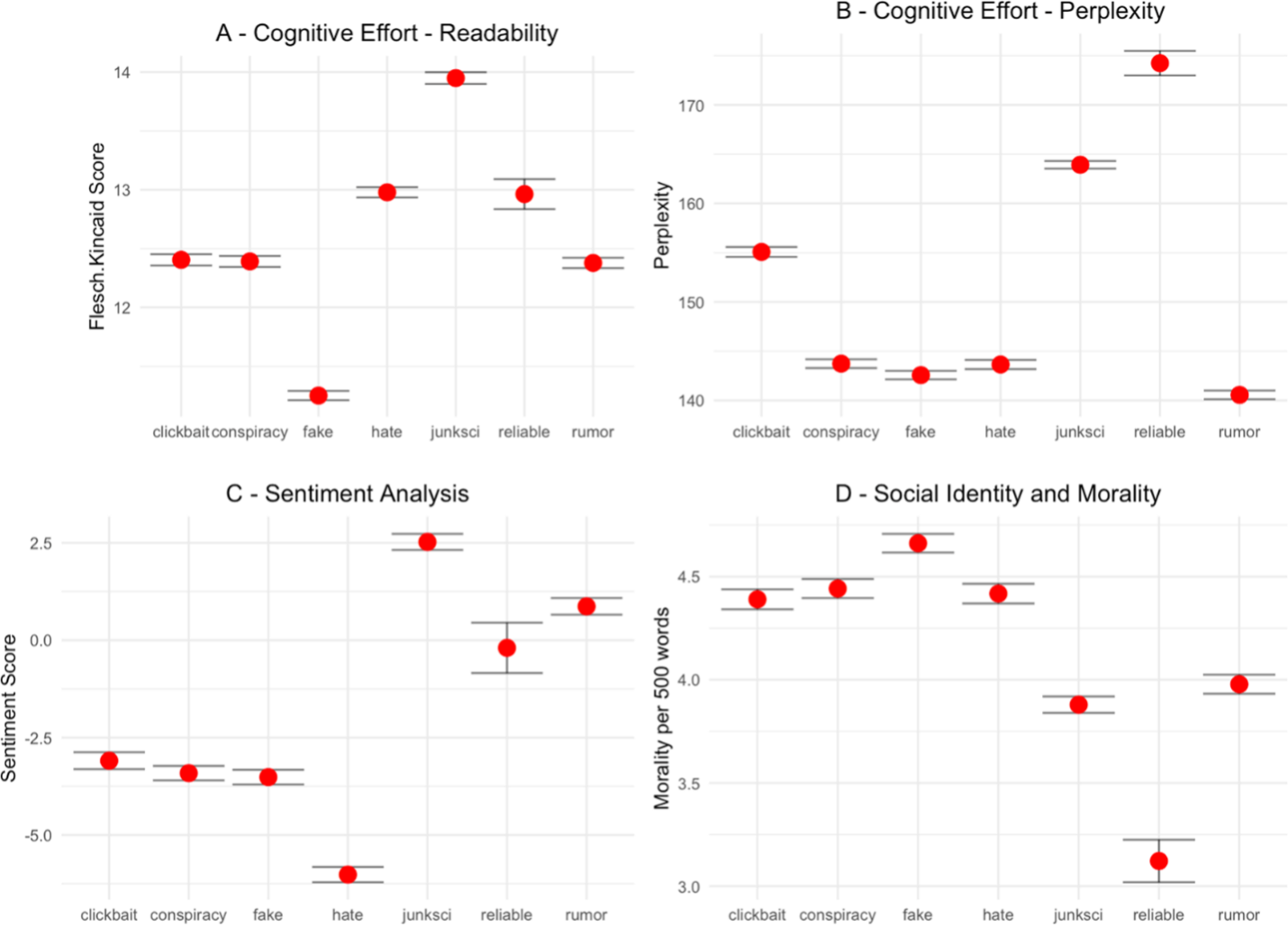

In a recent journal article, we compared clickbait, conspiracy theories, fake news, hate speech, junk science, and rumors articles with reliable news in terms of evocation of emotions (sentiment analysis and appeal to moral values and social identity) and cognitive effort (grammatical complexity and lexical diversity) using more than 92,000 articles. The results indicate that there are significant differences between the reporting style of reliable sources and misinformation types:

Source: Carrasco-Farré, C. (2022). The fingerprints of misinformation: how deceptive content differs from reliable sources in terms of cognitive effort and appeal to emotions. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1-18.

Source: Carrasco-Farré, C. (2022). The fingerprints of misinformation: how deceptive content differs from reliable sources in terms of cognitive effort and appeal to emotions. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 1-18.

The evidence shows that misinformation is less lexically diverse (15% less) and simpler in grammatical terms (as calculated through the readability score). Moreover, misinformation sources are also more appealing to emotions (10 times more negative than reliable sources) and, importantly, they rely heavily on implying threats to the social identity of the reader (37% more relying on moral values). In comparison, reliable sources are neutral in tone, which is what we would expect from traditional journalistic good practices. However, the problem appears when these media companies, in order to become more viral, are tempted to deviate from good practices of journalism to apply the same strategies that misinformation employs. That is, becoming more emotional, more moral, and simpler.

The problem with viral media strategies

While low quality and tabloid news providers have always existed, the need for webpage visitors and subscribers is a new temptation for higher quality providers to exploit misinformation strategies to attract them. However, this comes with unintended consequences for the whole society. While it may be financially beneficial from an individual organization’s point of view, compromising the journalistic practices of established media companies can contribute to the acclimation of the general public to more extreme content. Therefore, we propose some ideas to mitigate the unintended effects of the changing media ecosystem:

Increase users’ media literacy. The Internet and social media platforms have increased access to information – which is undeniably a good thing – but also have facilitated the proliferation of malicious actors pursuing economic and political agendas. The existing evidence shows that we have worryingly low levels of media literacy, especially in developing countries, to deal with this information overload. Usually, increasing media literacy levels is in the hands of governments and policymakers, who are responsible for education systems. Sadly, it is uncommon to find sufficient efforts made in terms of resources and reach.

Media organizations should continue to be our watchdogs. In parallel, when media organizations pursue strategies to reach higher virality, such as publishing a “catchy” headline appealing to the reader’s emotion and social identity, they become more and more similar to misinformation sources, which can erode the whole ecosystem, deepening the problem and forcing even more change in a negative loop of lowering journalistic standards. By adopting these misinformation strategies they make it more complicated for users to discern between what is factual information and what is not. In conjunction with low media literacy rates, this becomes a perfect storm.

Media companies and social media platforms have a duty towards society to ensure provision of truthful information without falling into the temptation of going viral for financial gains. If not, the ability to discern what is true from what is false is weakened, which leads to an eventual degradation of societies at large. We have already seen the offline impact of misinformation and how it escalates into physical violence, major democratic disruptions, or the rise of populism and post-truth politics. As our societies are becoming more digitalized, the problem is likely to grow bigger if we do nothing to stop it, and media organizations are (were?) the best watchdogs against it.

This article reflects the views of the author and not those of the Media@LSE blog nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Filip Mishevski on Unsplash